|

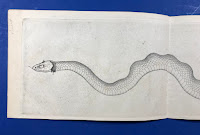

| Diagram of the supposed Gloucester Sea Serpent. |

In honor of this year’s Winter Carnival theme - "A Blizzard of Unbelievable Beasts" Rauner is hosting an interactive exhibit featuring books from the Renaissance through the 19th-century which document the many fantastic beasts - from unicorns to griffons to sea serpents - which were thought to roam the less-explored lands and oceans around the globe. One of our favorite items which will be on display this afternoon for our “Unbelievable Beasts” exhibit is the aforementioned Gloucester sea serpent report, titled “Report of a Committee of the Linnaean Society of New England Relative to a Large Marine Animal, Supposed to be a Serpent, seen near Cape Ann, Massachusetts in August 1817.”

The Linnaean Society of New England (1814–1822) was established in Massachusetts, to promote the study of natural history. The Society ran a science museum, arranged lectures on topics ranging from mineralogy to ornithology, and excursions for its members. Before it became a central figure in the so-called “Gloucester sea serpent debate”, in the summer of 1816, society members travelled through Hanover on their way to explore New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Whilst in New Hampshire, the group surveyed Mount Monadnock and Ascutney among others, studying their mineral composition and searching for new species (they documented 4 new species of plants).

On August 18th, 1817, the Linnaean Society convened to investigate reports of an extraordinary “sea serpent” which had been making waves (pun intended) around Gloucester and Cape Ann, Massachusetts. The group formed an investigative committee which created systematic questionnaires, each containing 25 targeted questions meant to ascertain the nature of the sea serpent, including “How many distinct portions were out of the water at one time?” and “Had it gills and breathing holes, and where?” Within a few days after the initial sightings had been reported, the three committee members and the “Honorable Lonson Nash of Glouchester” met with 11 locals who professed actually to have seen the animal in question, first asking them to explain everything they remembered from the sea serpent encounter, and then recorded their responses to targeted questions. In order to keep the report as ‘scientific’ as possible, the examinations were done separately, and “the matter testified by any witness (was) not to be communicated until the whole evidence was taken.”

According to eyewitnesses, the serpent was between “eighty and ninety feet in length and about the size of a half barrel, apparently having joints from its head to its tail.” Contrary to the typical renditions of glistening green sea serpents, the majority of the accounts describe the creature as a dull dark brown without any spots. The creature was capable of moving at extraordinary speeds, as according to one testimonial it could “travel a mile or two in three minutes” and even faster underwater. Although the serpent was observed during midday in most cases, it’s rather shy nature and quick movements made it difficult for any of the observers to get a good look at its facial features. Despite a general consensus on it’s large size, scaly skin, and fast undulating movements, it’s face looked “much like the head of a sea turtle” to one observer, yet “formed something like the head of the rattlesnake, but nearly as large as the head of a horse” to another fishermen who observed it the same day. The committee members asked witnesses whether they’d possibly mistaken other natural phenomena for a serpent, including “a number of porpoises following each other in a train”, but the answer was always a resounding “no.” As one witness responded, “I was in a boat, and within thirty feet of him… I could see his scales.” To those who testified, there was apparently no doubt that they had encountered a large serpentine beast.

According to eyewitnesses, the serpent was between “eighty and ninety feet in length and about the size of a half barrel, apparently having joints from its head to its tail.” Contrary to the typical renditions of glistening green sea serpents, the majority of the accounts describe the creature as a dull dark brown without any spots. The creature was capable of moving at extraordinary speeds, as according to one testimonial it could “travel a mile or two in three minutes” and even faster underwater. Although the serpent was observed during midday in most cases, it’s rather shy nature and quick movements made it difficult for any of the observers to get a good look at its facial features. Despite a general consensus on it’s large size, scaly skin, and fast undulating movements, it’s face looked “much like the head of a sea turtle” to one observer, yet “formed something like the head of the rattlesnake, but nearly as large as the head of a horse” to another fishermen who observed it the same day. The committee members asked witnesses whether they’d possibly mistaken other natural phenomena for a serpent, including “a number of porpoises following each other in a train”, but the answer was always a resounding “no.” As one witness responded, “I was in a boat, and within thirty feet of him… I could see his scales.” To those who testified, there was apparently no doubt that they had encountered a large serpentine beast.Although most of the Gloucester sea serpent encounters documented in our committee report were rather uneventful - often involving the animal swimming by and occasionally stopping at the surface of the water to apparently rest and survey its surroundings - the seventh witness, Matthew Gaffney, had a rather frightening experience. Gaffney, a ship carpenter from Gloucester, recalled that on August 14th, 1817, he saw the sea serpent between 4 and 5 o’clock in the afternoon when he was out in the harbor sailing his personal vessel with his brother Daniel and friend Augustin Webber. As Gaffney explains it, “I was within thirty feet of him. His head appeared full as large as a four-gallon keg; his body as large as a barrel, and his length that I saw, I should judge forty feet, at least…. I fired at him, when he was nearest to me. I had a good gun, and took good aim. I aimed at his head, and think I must have hit him. He turned towards us immediately after I had fired...he was coming at us.” The scene didn’t end with an epic Jaws-worthy fight however, for as soon as the creature was hit it “sunk down and went directly under our boat, and made his appearance at about one hundred yards from where he sunk… (he) continued playing as before.” Gaffney was incredulous that he was unable to kill or otherwise wound the animal, making sure to highlight his marksmanship skills in the interview, stating, “My gun carries a ball of eighteen to the pound; and I suppose there is no person in town, more accustomed to shooting, than I am.”

So, what precisely did the Committee of the Linnaean Society conclude about the sea serpent? They don’t state a definite “yes” or “no” answer, however if the report were a Magic 8-ball it would read “All signs point to yes.” For example, the report includes illustrations of a smaller Cape Ann sea animal actually examined and dissected, which the authors likened to "a remarkable serpent, supposed to be the progeny of the great serpent." The small serpent, which had unusual bumps along its back, was taken as concrete evidence that a larger sea serpent must exist. Additionally, to accommodate their ‘discovery’, the Linnaean Society established a new genus - Scoliophis Atlanticus - and included a diagram of what the adult animal must look like at the front of their report. As the reporters remarked following their interview sessions, “the deponents were interrogated separately, no one knowing what the others had testified, and though they differ in some few particulars, still, for the most part, they agree.”

So what happened to the Gloucester sea serpent, and what about the supposed baby serpent collected in Cape Ann? At first the reports led to impassioned debates on both sides about the creatures' existence. An editor of the Philadelphia newspaper at the time wrote an editorial stating. “The evidence of the existence of the Sea-Monster is conclusive and irresistible.” Perhaps it was too irresistible though, as a French naturalist that acquired the supposed baby sea serpent soon concluded what had been thought to be a new species was in fact a common black snake (Coluber contrictor) whose spine undulated due to a skeletal disease. As the news broke, scholars questioned the validity of the Society’s report, and when the group disbanded in 1822 nobody followed up with further inquiries. Perhaps local residents of Gloucester really did see a remarkable marine animal in the summer and fall of 1817, but we’ll likely never know for sure.

To read this sea serpent story for yourself, stop by Rauner Library today and ask to see Rare QL 89.2.S4 L56 1817.

No comments :

Post a Comment