In 1669, Swammerdam published his Historia, which disproved the prevailing Aristotelian perspective that insects were inferior creatures which lacked any sort of internal anatomy worth mentioning. Additionally, Swammerdam argued that insects came from eggs instead of spontaneous generation, which was a widely-held Christian notion at the time. Swammerdam is today often cited as ushering in a natural theology that took hold in the 1700s, wherein the glory of God was revealed by careful scientific examination of his various creatures. He also was an innovator with regard to scientific techniques for working with scientific specimens, both insect and human.

Friday, January 24, 2020

Creepy-Crawlies

If you like old tomes and creepy-crawlies, then do we ever have the book for you. In preparation for an anthropology class on bestiaries, we discovered an edition of Jan Swammerdam's Historia Insectorum Generalis that was printed in 1685. Inside, a cornucopia of detailed engravings of insects are lovingly tipped in. The high quality of the images is almost reminiscent of Vesalius's anatomy of the human body, which makes sense once one learns that Swammerdam initially trained as a physician. In fact, his love of insects derailed his father's plans for him to become a wealthy and prominent doctor. In anger, his father withdrew financial support and Swammerdam was forced to practice medicine in order to make enough money to continue his entomological research.

In 1669, Swammerdam published his Historia, which disproved the prevailing Aristotelian perspective that insects were inferior creatures which lacked any sort of internal anatomy worth mentioning. Additionally, Swammerdam argued that insects came from eggs instead of spontaneous generation, which was a widely-held Christian notion at the time. Swammerdam is today often cited as ushering in a natural theology that took hold in the 1700s, wherein the glory of God was revealed by careful scientific examination of his various creatures. He also was an innovator with regard to scientific techniques for working with scientific specimens, both insect and human.

To explore the amazing world of insects contained within the first Latin edition of Swammerdam's work, come to Special Collections and ask to see Rare QL463 .S8.

In 1669, Swammerdam published his Historia, which disproved the prevailing Aristotelian perspective that insects were inferior creatures which lacked any sort of internal anatomy worth mentioning. Additionally, Swammerdam argued that insects came from eggs instead of spontaneous generation, which was a widely-held Christian notion at the time. Swammerdam is today often cited as ushering in a natural theology that took hold in the 1700s, wherein the glory of God was revealed by careful scientific examination of his various creatures. He also was an innovator with regard to scientific techniques for working with scientific specimens, both insect and human.

Tuesday, January 21, 2020

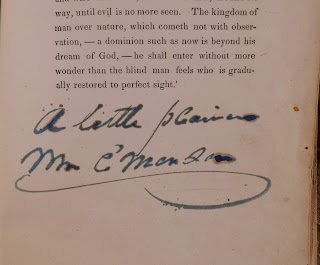

A Little Plainer Mr. Emerson

Dartmouth students in the 19th century had a habit of tweaking the sensibilities of their nervous professors. The school was a factory for missionaries, members of the clergy, lawyers, and teachers--not exactly the most radical professions of the time--and the faculty were strict and conservative in their views of culture. So, in 1838, the Dartmouth Literary Societies invited the bad boy of the American intelligentsia, Ralph Waldo Emerson, to speak at their Class Day celebrations.

Dartmouth students in the 19th century had a habit of tweaking the sensibilities of their nervous professors. The school was a factory for missionaries, members of the clergy, lawyers, and teachers--not exactly the most radical professions of the time--and the faculty were strict and conservative in their views of culture. So, in 1838, the Dartmouth Literary Societies invited the bad boy of the American intelligentsia, Ralph Waldo Emerson, to speak at their Class Day celebrations.On July 24th, 1838, Emerson stood before the class and orated on his Transcendentalist views. God is not found in the Bible but in Nature! Blasphamy, scandal! He also threw in a critique of education in America that was not particularly flattering. Worse yet, the speech occurred just nine days after Emerson delivered his scathing Harvard Divinity School Address that shook Harvard, the Unitarian church, and American thought in general.

Emerson gave the Literary Societies a little present when he was here: an inscribed copy of the first edition of his Nature published two years earlier. His copy was placed into the Social Friends' Library then became part of the Dartmouth Library in the late-19th century. The book was well read. On the inside flap are notes from various readers and there are bits of marginalia throughout as curious readers tried to puzzle out Emerson's prose.

But the best comment comes right at the end. The frustration of a confused student is expressed in his scrawl across the bottom of the final page: "A little plainer Mr. Emerson." If you want to learn more, listen to our Hindsight is 20/19 podcast episode for the 1830s.

To see the book, ask for Val 816Em3 T614.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)