The story of Dartmouth Hall’s bell begins with the initial founding of the College. Realizing the need to announce church services, meetings, and class periods in addition to instituting a “town clock” in the woods of New Hampshire, Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth’s first president, pleaded with his financial supporters in England to help him raise funds to purchase a bronze bell. At the time, quality bells (i.e., bells that did not crack under heavy use) were extremely expensive, and as such Eleazar was forced to rely upon a large conch shell, which he and undergraduate students blew into, to announce class periods and to call worshipers to prayer.

The first College bell was found to be broken upon its arrival from Whitefield, NH, in 1789, thus marking the beginning of the long line of short-lived Dartmouth Hall bells. On August 8, 1790, then Dartmouth senior William Eaton, who would later become famous Army General William Eaton and Consul General to Tunis during the First Barbary War, was dispatched by Dartmouth President John Wheelock to procure a bell cast at Messrs Doolittle and Goodyear in Hartford, CT, for commencement. The 282-pound bell was hung on August 24, 1790, in the new belfry of Dartmouth Hall, marking the beginning of 138 years of Dartmouth Hall bells ringing across campus. In 1819, during the famous Dartmouth College Case, Dartmouth College and Dartmouth University argued over ownership of the bell, given that its chiming symbolized control over class and religious service schedules. Eventually, the bell was appropriated along with other pieces of college property to the short-lived University, but was relinquished back to the College following Daniel Webster’s successful case.

In October 1819, the Dartmouth Hall bell broke and was replaced by a 299-pound Revere bell (one of only 398 bells produced by Paul Revere’s foundry between 1792 and 1828) brought from Boston. This bell was then traded for a larger 512-pound bell, also from Revere’s foundry, in February, 1821. In 1829, following renovations to Dartmouth Hall, a deeper-toned bell of 726 pounds was installed, where it rang for over 40 years until it cracked in 1867. During the 1850s-1880s, one of the favorite pranks of Dartmouth students was to “steal the clapper off the bell, or ring it before the recitation period was fully over” (pg. 20, A Social & Architectural History of Dartmouth Hall). By the 1870s, the eagerness of students to climb Dartmouth Hall to ring the largest bell before the end of class periods and before sunrise had grown problematic. To prevent this practice, the disgruntled faculty gradually boarded up entrances to the Dartmouth Hall belfry and even posted a guard. Many ingenious devices were thus invented to ring the bell from a distance, one sophomore going so far as to climb the lightning rod with a long stick in hand, having fastened a rope to the eaves as a means of escape. Unfortunately, the rope was discovered by faculty and cut off about 3 feet below the eaves, so that upon using it, the boy dropped three stories to the ground. Our records indicate that the student limped away before the faculty could catch him.

As both the size and reputation of Dartmouth College grew, so did the size and reputation of Dartmouth Hall’s bell. From 1867-1885, Dartmouth Hall went through a succession of four bells which had an uncanny tendency to break shortly after their warranty periods had expired, all the while more than doubling in size from 512 to 1,237 pounds. Despite their growth and the continued importance of Dartmouth Hall as a recitation hall, dormitory, chapel, library, and medical school, the building which supported the Dartmouth Hall bells had fallen into neglect. In 1887, President Bartlett praised the “harmony of the bell” which called him to work in the morning, but described Dartmouth Hall as a “menace” due to its dilapidated state and the infamous “bedbug alley” dorms which occupied the top-most floor. Renovations to the belfry proved short lived however, as the bells melted in the famous 1904 fire which consumed most of Dartmouth Hall.

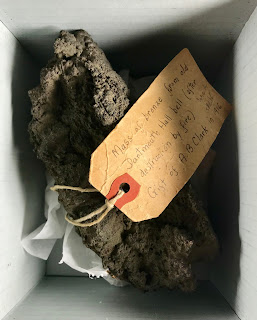

Dartmouth students and alumni had grown so fond of the Dartmouth Hall bells that after melted remnants of the bell were found amid the smoldering timbers following the 1904 fire, hundreds of small replica bells were made from the hunk of bronze. These small souvenir bells were used as watch fobs; given as gifts to alumni, trustees of the college, and local families, often labelled with the inscription: “made from fragments from the eight ancient bells of Dartmouth Hall which called the students together from 1786-1904.” Today, several of these beautiful Dartmouth Hall bell replicas can be heard chiming here at Rauner Special Collections Library, where they are housed in our realia room.

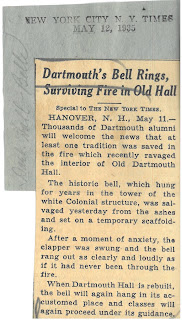

After the 1904 fire, Joshua W. Pierce (class of 1905) gifted the college with a 1,184 pound bell also from Meneely & Co., which was installed on September 27, 1905. The bell continued chiming the hour and signaling class schedules until the construction of Baker Library in 1928, after its role in signaling church services had been passed in 1888 to Rollins Chapel. In a stroke of luck, the Dartmouth Hall bell survived the 1935 fire which consumed the roof of the building, but has remained largely unused.

Despite hanging in silence, Dartmouth Hall’s bell continued to make headlines when news broke in October of 1954 that a group of undergraduates had stolen the 70-pound clapper. The self-declared “Clapper-Nappers” left a ransom note with the college newspaper, stating:

Here are the facts on why the late bell doesn’t ring anymore. We have stolen the clapper from the top of Dartmouth Hall. It is now hidden within two miles of Hanover… we will return the clapper when Dartmouth becomes coeducational.Aside from using the bell clapper heist as a gesture of frustration over the administration’s inability to move toward coeducation, the Clapper-Nappers also ended their ransom letter on a lighter note, saying “We hope unpunctual students... appreciate our efforts to revive the old College tradition (of stealing the Dartmouth Hall bell clapper).”

|

To learn more about the Dartmouth Hall bells, ask for the vertical file "Dartmouth Hall - Bells", or ask to see our parts and replicas of the Dartmouth Hall bell by asking for Realia Box 26. More images of the various iterations of Dartmouth Hall and the Dartmouth Hall belfry can also be found in the photo file "Dartmouth Hall - Old."