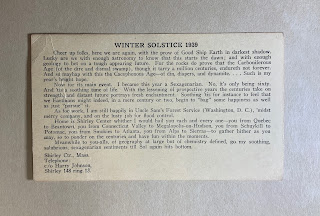

Today is the shortest day of the year and so we'll be quick as well. If you want to read Benton's funny little cards, ask for Box 192 of the MacKaye Family papers (ML-5). Until next time, Happy Solstice and we'll see you in the New Year!

Wednesday, December 21, 2022

Friends and Fellow-Culprits

Friday, December 16, 2022

Hanukkah Hijinks

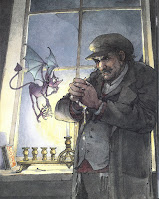

This Sunday marks the first night of Hanukkah, a Jewish festival that lasts for eight nights and days. The festival celebrates the Jewish people's liberation of Jerusalem from the Seleucid Empire of Syria and the rededication of the Temple in 164 BCE. Upon regaining the Temple, the Maccabees discovered that all of the ritual olive oil had been profaned except for one sealed jar. Although that jar contained only enough oil to keep the menorah lit for a single day, the flames miraculously burned for eight continuous days, long enough to prepare more oil. Using a shamash, or "helper candle," one candle is lit on each night of the eight-day festival until all nine candles glow brightly on the last evening. The menorah is usually placed in a window or other location of high visibility, because its light is meant to remind those who see it of the miracle of Hanukkah.

This Sunday marks the first night of Hanukkah, a Jewish festival that lasts for eight nights and days. The festival celebrates the Jewish people's liberation of Jerusalem from the Seleucid Empire of Syria and the rededication of the Temple in 164 BCE. Upon regaining the Temple, the Maccabees discovered that all of the ritual olive oil had been profaned except for one sealed jar. Although that jar contained only enough oil to keep the menorah lit for a single day, the flames miraculously burned for eight continuous days, long enough to prepare more oil. Using a shamash, or "helper candle," one candle is lit on each night of the eight-day festival until all nine candles glow brightly on the last evening. The menorah is usually placed in a window or other location of high visibility, because its light is meant to remind those who see it of the miracle of Hanukkah.Here at Rauner, we are preemptively celebrating Hanukkah by reading through our copy of Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins, a wonderfully illustrated children's book written by Eric Kimmel and illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman of Lyme, New Hampshire. This charming rendition of an old Jewish folktale received the distinction of being a Caldecott Honor Book in 1990; it recounts how Herschel of Ostropol outwitted a motley pack of goblins who were preventing a small village from celebrating Hanukkah. The titular character, who appears in several Yiddish folktales, is believed to be based on an actual person who lived in western Ukraine in the 1800s. To look through this beautiful edition of an enduring tale, come to Rauner and ask to see Illus H997kih.

Friday, December 9, 2022

Maxfield Parrish's Palette

Earlier this week, or perhaps it was last week, we had the good fortune to witness a beautiful sunset while walking out onto the Green. The radiant pink and purple clouds were stunning with the blue sky behind them, and it brought to mind the color palette of a certain painter and illustrator who lived and died in Plainfield, New Hampshire, only a dozen miles or so from the Dartmouth campus. Maxfield Parrish was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1870; he was raised in a Quaker society and attended Haverford College, like any good Pennsylvania Quaker should. He then attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and studied under Howard Pyle at the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, & Industry.

Earlier this week, or perhaps it was last week, we had the good fortune to witness a beautiful sunset while walking out onto the Green. The radiant pink and purple clouds were stunning with the blue sky behind them, and it brought to mind the color palette of a certain painter and illustrator who lived and died in Plainfield, New Hampshire, only a dozen miles or so from the Dartmouth campus. Maxfield Parrish was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1870; he was raised in a Quaker society and attended Haverford College, like any good Pennsylvania Quaker should. He then attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and studied under Howard Pyle at the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, & Industry.In 1898, Parrish and his wife moved to Plainfield, where he became an

important member of the Cornish Art Colony. Famous sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens was at the center of this gathering of artists and other creatives, which at times swelled to nearly one hundred people in size. After Saint-Gaudens died in 1907, the colony slowly dissolved. However, the Upper Valley had clearly made an impression on Parrish. He continued on in New Hampshire until 1966 when he died here at the ripe old age of 95.

Parrish was a wildly successful illustrator for over fifty years and the Upper Valley was his muse. Whenever we step outside and behold the glory of another New Hampshire/Vermont sunset, we always feel a kinship with him and, perhaps, that same sense of awe that he first felt upon settling here. Come to Rauner if you want to stumble upon even more stunning vistas within the Maxfield Parrish papers (ML-62).

Friday, December 2, 2022

Predicting the Plague (and curing it!)

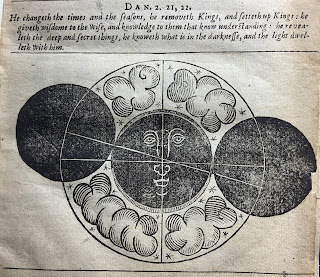

Just three years earlier, Charles the I was executed. Everything was turned on its head, and something big was afoot. Culpeper deduced that the eclipse heralded the second coming, so he wrote a pamphlet explaining the eclipse and issuing his dire warnings. Among his many predictions were a great plague and a fire. He got that right, but he was a little quick on the trigger. In 1665 London was hit by the Black Plague, and the following year, ravaged by the Great Fire.

As a physician, Culpeper was ready to help. He died in 1654, but he left behind a truly bizarre cure for the plague that you can read about here.

To read about the eclipse and its threats, ask for Nicholas Culpeper's Catastrophe magnatum: or, The Fall of the Monarchie. A Caveat to Magistrates, Deduced from the Eclipse of the Sunne, March 29 1652 (London: T. Vere and Nathe, 1652).

Tuesday, November 22, 2022

Thankful, But Not Sentimental

Of all of the many amazing collections that we are fortunate to have here in Special Collections, I think that my favorite is the treasure trove of numerous student letters written to home from Dartmouth. Today, while hunting about for a Thanksgiving-related item to blog about, I found a charming little collection of letters written by Richard "Dick" Campen, member of the class of 1934. Campen was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, and so going home for Thanksgiving every year wasn't really an option.

Of all of the many amazing collections that we are fortunate to have here in Special Collections, I think that my favorite is the treasure trove of numerous student letters written to home from Dartmouth. Today, while hunting about for a Thanksgiving-related item to blog about, I found a charming little collection of letters written by Richard "Dick" Campen, member of the class of 1934. Campen was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, and so going home for Thanksgiving every year wasn't really an option.Luckily, Campen had an Aunt Lil and Uncle Abe who lived in Hartford, Connecticut, and so one year he went down to stay with them for the holiday. In a letter written to his parents November 27, 1930, Campen says that he had piled into a Chrysler sedan with "six other fellows going to New York." On the drive down, the students passed numerous other cars "packed to the rumble seat" with Dartmouth students also headed home for Thanksgiving.

Campen's description of his time at his relatives' home is charming, and he clearly valued many of

the same sorts of creature comforts that students today celebrate upon returning to their families for a break from school. He raves about the food, whether a "tasty plate" of lamb chops, a glass of "precious" orange juice, or "scarce" boiled eggs. In particular, Thanksgiving dinner was delicious: turkey, cranberries, and "all the rest." Over dinner, he chatted with a guest who was a student at Williams College about the similarities and differences at their respective educational institutions. Ultimately, he decided that the Williams student was a "nice fellow."

the same sorts of creature comforts that students today celebrate upon returning to their families for a break from school. He raves about the food, whether a "tasty plate" of lamb chops, a glass of "precious" orange juice, or "scarce" boiled eggs. In particular, Thanksgiving dinner was delicious: turkey, cranberries, and "all the rest." Over dinner, he chatted with a guest who was a student at Williams College about the similarities and differences at their respective educational institutions. Ultimately, he decided that the Williams student was a "nice fellow."In closing, Campen says, "I'm very thankful for everything, but I don't want to bore you with a lot of sentiment." Like him, we're thankful for so many things about Dartmouth, mostly the students, faculty, and staff who all strive to make it an even better place in the future while not getting overly sentimental about its past.

Friday, November 18, 2022

The (Rail)road to Hell

Sometimes the road to Hell isn't paved with good intentions but propaganda and deceit. In 1937, Fanny Bartlett of Norwich, Vermont, wrote a sympathetic letter to Taneo Taketa, the manager of the South Manchuria Railway Company's New York branch. Fanny was the wife of Samuel Concord Bartlett, Jr., salutatorian of Dartmouth's class of 1887 and son of Dartmouth's eighth President. Before the Bartletts had retired to Norwich the previous year, they had been missionaries in Japan for a total of thirty-two years. Bartlett Jr. had been a lecturer and chaplain at Doshisha University in Kyoto, and had been awarded emeritus status by the university upon his retirement. During his chaplaincy, Fanny had served as the dean of women for Doshisha's associated women's school. Sadly, not soon after their return to Vermont, Bartlett died in February of 1937.

Sometimes the road to Hell isn't paved with good intentions but propaganda and deceit. In 1937, Fanny Bartlett of Norwich, Vermont, wrote a sympathetic letter to Taneo Taketa, the manager of the South Manchuria Railway Company's New York branch. Fanny was the wife of Samuel Concord Bartlett, Jr., salutatorian of Dartmouth's class of 1887 and son of Dartmouth's eighth President. Before the Bartletts had retired to Norwich the previous year, they had been missionaries in Japan for a total of thirty-two years. Bartlett Jr. had been a lecturer and chaplain at Doshisha University in Kyoto, and had been awarded emeritus status by the university upon his retirement. During his chaplaincy, Fanny had served as the dean of women for Doshisha's associated women's school. Sadly, not soon after their return to Vermont, Bartlett died in February of 1937.Eight months or so later, Fanny penned her letter to Taketa. At that particular moment, the Japanese Empire was in the midst of the Battle of Shanghai, which lasted from August 13 until November 26 and was one of the bloodiest battles of the entire Second Sino-Japanese War. Unfortunately, we don't have a copy of Fanny's letter, but we do have Taketa's response. He says that he is "deeply moved" by Bartlett's "very kind letter" and praises her "understanding and faith in Japan." He stresses that "not a single Japanese has wished to kill a Chinese, nor break up the Chinese Government" but that Japan was compelled to take action because of implied Chinese aggression.

The fact that Taketa worked for the South Manchuria Railway Company, or Mantetsu, is a very important detail. Mantetsu was the backbone of Japan's extractive colonialist agenda in China during this period. Its freight fees provided 25% of Japan's tax revenues in the 1920s alone. A supposed attempt to detonate Mantetsu railway tracks in 1932 was actually a false flag event initiated by Japan that provided the pretext for their immediate invasion of northeastern China. The rail company then served as Japan's unofficial governing body within the puppet state of Manchuria.

It is difficult, therefore, to believe Taketa's protestations of Japan's desire for peace and goodwill with China. He ends his letter to Mrs. Bartlett by urging her to tell all her friends about the "real spirit of Japan" and says that he has added her to the South Manchurian Railway Company's mailing list so that the literature he sends her might help her to convince her friends of Japan's "true intentions." Less than two months later, the Japanese army would begin a six-week massacre of the Chinese inhabitants of Nanjing, estimated to have resulted in approximately 200,000 civilian murders and 20,000 instances of rape, as well as widespread arson and looting.

To read this letter, and to look through other correspondence that Fanny Bartlett received, come to Special Collections and ask to see Box 8 of the Fanny and Samuel C. Bartlett, Jr., Papers (ML-75).

Friday, November 11, 2022

An Unsuccessful Rescue Mission

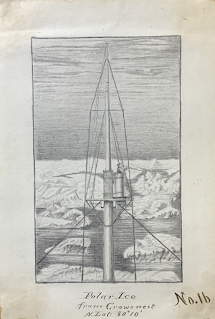

In July of 1879, the USS Jeannette left San Francisco and headed for the Bering Strait, intent on reaching the North Pole. The expedition was betting on the proposition that the warm water currents off the coast of Japan would carry them north through the strait and into an Open Polar Sea (a soon-to-be debunked theory of ice-free waters surrounding the Pole). This ambitious trip was rather disastrous, as the Jeannette became stuck in pack ice in September and drifted on until it was finally crushed by the pressure of the ice in June of 1881. The crew then took to sledges and whaleboats, attempting to travel through the ice to the Siberian coast. Of the 33 men taking part in the expedition, only 13 survived to return to the U.S.

In July of 1879, the USS Jeannette left San Francisco and headed for the Bering Strait, intent on reaching the North Pole. The expedition was betting on the proposition that the warm water currents off the coast of Japan would carry them north through the strait and into an Open Polar Sea (a soon-to-be debunked theory of ice-free waters surrounding the Pole). This ambitious trip was rather disastrous, as the Jeannette became stuck in pack ice in September and drifted on until it was finally crushed by the pressure of the ice in June of 1881. The crew then took to sledges and whaleboats, attempting to travel through the ice to the Siberian coast. Of the 33 men taking part in the expedition, only 13 survived to return to the U.S.This is not the story of how the Jeannette survivors were rescued. Instead, it is the story of an expedition that didn't even come close to rescuing them. By 1881, there was worry enough regarding the Jeannette's disappearance that two Navy ships were dispatched to search for the crew. The USS Rodgers was sent on the same path the Jeannette took: through the Bering Strait. In a supremely unlucky turn of events, the ship was destroyed by a fire and the rescue crew themselves had to be saved.

Meanwhile, the USS Alliance was sent to look on the other side of the North American continent between Iceland, Norway, and Svalbard. Although that was over 4,000 miles from where the Jeannette actually ended up, there was arguably a chance that the ship had made it over the top of the continent and come out on the other side. Whether or not this was ever a real possibility, the newspaperman James Gordon Bennett Jr., who had funded the Jeannette expedition, pushed hard for the secondary search to be made. He also took steps to ensure he'd get the scoop on any resulting news. He placed a reporter on board the Alliance and requested photographs from the trip. A camera could not be acquired in time for the ship's departure and so one of the crew members made a series of sketches instead.

And this is what brings us to today's piece of the collections, if you'll forgive the long prologue. Jefferson Brown, an assistant engineer on the Alliance, made a series of about thirty (surviving) sketches along the way, documenting icy landscapes, shipwrecks, polar bears, and more. Some were reproduced in print later when Brown had his own account of the trip published, but others appear to exist only within this disbound sketchbook carried all around the Northernmost waters of the Atlantic Ocean in 1881. The Alliance wouldn't find any trace of the doomed Jeannette expedition, but its crew would see a part of the world that the United States had shown little interest in up to that point. They collected data on water currents and temperatures, specimens of regional flora and fauna, and observations on phenomena ranging from the movement of pack ice to the Northern Lights. It wasn't much of a rescue mission, but if Brown's work is anything to go by, it must have been quite the trip.

To see Brown's sketches and read his account of the Alliance's journey, ask for Stefansson Mss-184.

Friday, November 4, 2022

What in the Blazes?

In my work I often come across curious or odd organizations. They are usually created by men who are trying to exclude and/or control other members of society. The one I came across today, however, was created so that its members could police their own behavior. Let’s hear it for the "Society of Self-Watchers". What are they watching themselves for, you may ask? Profane swearing, which is defined as "swearing that constitutes sin and shows a lack of respect for all things held sacred".

In my work I often come across curious or odd organizations. They are usually created by men who are trying to exclude and/or control other members of society. The one I came across today, however, was created so that its members could police their own behavior. Let’s hear it for the "Society of Self-Watchers". What are they watching themselves for, you may ask? Profane swearing, which is defined as "swearing that constitutes sin and shows a lack of respect for all things held sacred".There is actually a long history in the West of legalistic attempts to protect society from blasphemous utterings. Laws were put in place beginning with the Profane Swearing Act in England in 1694, and followed by the Profane Oath Act in 1745, which was not repealed until 1967. The United States had similar laws that fined people for profane swearing in public. The state of Virginia, for example, did not repeal its profanity law of 1792 until 2020.

The Society of Self-Watchers was founded in Hanover, New Hampshire on February 16, 1856. The group created a preamble and resolutions that declared that "the sin of profane swearing is a vice so mean and so low that every person of sense and character will detest and despise it"....acknowledge the higher authority of him who has commanded “Thou shall not take the name of the Lord thy god in vain for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that take his name in vain.”and feeling the need of every possible restrained and protection against and unmanly and sinful habit so sadly formed, we do together agree to form ourselves into an Association of principle and practice opposed to the sin of profane swearing and do take for our watchword and motto, the precept of Christ our Savior, “Swear not at all”.

Resolved, that should we ever hear of one of our company using deliberately or hastily a profane word we will kindly remind him of our agreement by repeating to him our watchword "Swear not at all".Resolved, that we will receive kindly any similar report from our companions or from any other persons if we ourselves in any matter violate the principles we hear profess.

Friday, October 28, 2022

Dracula at 125

The novel is remarkable for its conflicted and complex depictions of gender and sexuality, played out in the characterization of both the monster and the heroes. Its not-so-complex depiction of race and foreign peoples marks it as a piece of invasion literature, where a colonizing population faces the anxiety that they will in turn be colonized. Count Dracula makes his way from Eastern Europe to London and begins to exert his influence over its more vulnerable inhabitants, spreading like a disease and reflecting Victorian fears about blood "purity." These themes feed into Dracula's status as one of the most influential horror stories of all time, and its impact on the genre continues to be relevant today.

Stoker himself had a lifelong love of the theater and spent nearly thirty years working for the English stage actor Henry Irving. With that in mind, today we're highlighting a book of plans replicating the Broadway version of Dracula designed by the master of the humorously macabre, Edward Gorey. The plans are intended to be cut out and assembled into a toy theater, though we've declined to take that step.

Come ask for Illus G675dra and take a look yourself. Happy Halloween...

Thursday, October 20, 2022

Days of Caring

Dartmouth has seen tough times before. To mark the day, two students, Sabrina Eager '23, and Kira Parrish-Penny '24, looked back through the archives to find other instances where the Dartmouth community came together after a tragedy with a compassionate response that made the campus a better place: the establishment of Dick's House in 1927; the response to the shootings at Kent State in 1970; and the memorial tributes to Karen Wetterhahn after her death in 1997. Sabrina and Kira have put together a pop-up exhibit that we will have out on Friday the 21st from 10:00-3:00 in our reading room. Please stop by.

Friday, October 14, 2022

New Exhibit: "Indigenizing an Institution"

On Monday, October 10, 2022, students belonging to the group Native Americans at Dartmouth (NAD) hosted a gathering on The Green in honor of Indigenous People's Day. Members of NAD distributed signs, read speeches, and presented poems to the 150+ individuals in attendance. The mood was somber, as students reflected on the historical oppression of Indigenous peoples as well as modern forms of violence enacted against their communities. However, the event was also celebratory, as members of NAD, or "NADs", emphasized the resilience of Indigenous peoples and their distinct cultural practices.

The style of assembly was not unique - in fact, Native students have orchestrated numerous events with the objective of raising awareness for Indigenous issues over the decades. Specifically, the past 50 years have witnessed NADs utilize petitions, demonstrations, symposiums, and more to share their concerns with others and advocate for pan-Indian causes. Commonly, such events were intended to counteract pervasive and harmful imagery, language, or "traditions" on campus related to Native representation. in other instances, such as the protests against Dartmouth's controversial investment in Hydro-Quebec, the tenacity of NADs ultimately benefited others.

Despite The College's foundational promise to educate Native youth, such affairs were neglected by the school for nearly 200 years, cultivating an environment that was hostile towards Indigenous peoples. By 1970, only nineteen Native students had graduated from Dartmouth, which likely contributed to the general disregard for Indigenous peoples and customs by others on campus. However, the re-dedication of the institution's commitment to instruct Native pupils occurred around this period, precipitating record numbers of Indigenous students matriculating at the college. In recent years, Indigenous voices (with the assistance of their allies) have been instrumental in producing positive change at Dartmouth, especially as it pertains to the Native community.

Our Lathem Special Collections Fellow, Sydnie Ziegler '22, has an exhibit called "Indigenizing an Institution," which aims to showcase the actions and achievements of Indigenous student advocacy since the 70s. It will remain on display in the Rauner Library foyer from October 10th through the end of November (Native American Heritage Month).

Friday, October 7, 2022

The Art of Gunboat Diplomacy

In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry steamed into Japanese waters with an impressive display of force. Four gunboats and a crew of soldiers demanded that Japan end its centuries-long isolation and open its borders to trade with the United States. It was a show of imperialist-minded moxie that rattled Japan.

In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry steamed into Japanese waters with an impressive display of force. Four gunboats and a crew of soldiers demanded that Japan end its centuries-long isolation and open its borders to trade with the United States. It was a show of imperialist-minded moxie that rattled Japan.

But there was also a fascination with these "Black Ships" and the odd manners, uniforms, and customs of the foreign power docked just off the coast, and a desire to spread the news of the wondrous visitation attracted Japanese artists. They created a series of "Black Ship Scrolls," long hand painted scrolls that depicted Commodore Perry's uninvited visit to Japan.We are fortunate to have one of these scrolls. It is an impressive sight--to us perhaps more impressive than Perry's gunships. The scroll is forty-six feet long on fine Japanese paper. The most stunning panel shows the ships at mooring, but the drawings of the soldiers and their uniforms show the exoticism of these foreign visitors. It is an intriguing artifact of a critical moment in Japanese and American history, where the United States flaunted its naval power to gain the concessions it wanted and Japan unwillingly began to open itself to the world.

Friday, September 23, 2022

Exhibit: A Fighting Tradition

.jpg) The Dartmouth College community has been involved in every one of the country's major military engagements, from as far back as the Revolutionary War all the way up to the recent conflicts in the Middle East. For centuries, Dartmouth men and women have carried on a storied tradition of valiant wartime service to the United States of America, serving all around the globe and in all branches of the military.

The Dartmouth College community has been involved in every one of the country's major military engagements, from as far back as the Revolutionary War all the way up to the recent conflicts in the Middle East. For centuries, Dartmouth men and women have carried on a storied tradition of valiant wartime service to the United States of America, serving all around the globe and in all branches of the military.During the 2022 fall term, an exhibit curated by Ryan Irving '24, current president of the Student Veterans Association, explores this tradition. "A Fighting Tradition: Dartmouth in American Wars" will be on display in Rauner Special Collections Library's Class of 1965 Galleries until December 3rd.As Irving's exhibit illustrates, this tradition has evolved over the years, as has the college's identity and the nature of its student body. In the first decade of Dartmouth's existence, its connection to war was primarily through alumni involvement. Over the course of the next two centuries, the college's participation in war efforts grew in scope and variety: it saw the creation of student military societies, facilitated the training of soldiers on campus, sponsored military support services, and allowed students to put their college years on pause to enlist.

National unrest over the country's involvement in the Vietnam War was reflected on campus by the formal elimination of ROTC sponsorship due in part to student protest. However, in the early years of James Wright's presidency, and because his influence at a national level, Dartmouth was afforded the opportunity to support the war effort in a new way: by welcoming veterans to campus as students, along with the wealth of experience and diversity that they brought with them.

To see the exhibit while it's on display, come by Webster Hall and visit the exhibit space on our mezzanine. To read more about the exhibit online, visit its website.

Friday, September 16, 2022

Representing Lust (and Chastity!)

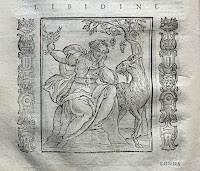

The use of emblems was popular during the Baroque time period in Italy and Europe in general, serving as a guide and source of inspiration for artists, poets, and sculptors when they were looking to creatively represent virtues, ideas, or even animals.

The use of emblems was popular during the Baroque time period in Italy and Europe in general, serving as a guide and source of inspiration for artists, poets, and sculptors when they were looking to creatively represent virtues, ideas, or even animals.Cesare Ripa’s Noua Iconologia, printed in 1618, takes an encyclopedia-like format, alphabetically categorizing his emblems in multiple sections: Main Images (in 3 parts), More Notable Things, Animals, Colors and Metals, Gestures and the Human Body, Artificial Objects, Fish, and Plants. With each emblem description, Ripa also includes allegorical interpretations and references famous philosophers and writers of the time, whose interpretations of a particular object or virtue influenced his depiction of it.

Take the examples of Lust (Libidine) and Chastity (Castità). Ripa writes that the woman that symbolizes

Chastity in his emblem dresses in white to represent “the purity of the spirit, which maintains this virtue” (“Vestesi questa donna di bianco per rappresentare la purità dell'animo, che mantiene questa virtù.” (77).) and we see an association of colors with the value of chastity, but even more importantly, there is a suggestion that chastity leads to strength and truthfulness of character, as though someone who isn’t chaste is deceitful. Similarly, the emblem of Lust uses a particularly large amount of animal imagery, from beaks to panthers, all of which Ripa says symbolize lust, whose beauty “devours time, money, fame, body, and soul and spits it out becoming a slave to sin and the devil” (“Il che molto è simile alla Libidine, la quale con la bellezza ci lusinga, e tira, poi ci divora, perché ci consuma il tempo, il dannaro, la fama, il corpo, e l'anima istessa ci macchia, e ci avvilisce, facendola serva del peccato, e del demonio.” (312)). This, therefore, adds an element not just of deception, but of monstrosity and of sin, bringing in a religious element as well. Lust, according to Ripa, derives in women not even solely on a sexual level but also on the pursuit of fame and money.

Chastity in his emblem dresses in white to represent “the purity of the spirit, which maintains this virtue” (“Vestesi questa donna di bianco per rappresentare la purità dell'animo, che mantiene questa virtù.” (77).) and we see an association of colors with the value of chastity, but even more importantly, there is a suggestion that chastity leads to strength and truthfulness of character, as though someone who isn’t chaste is deceitful. Similarly, the emblem of Lust uses a particularly large amount of animal imagery, from beaks to panthers, all of which Ripa says symbolize lust, whose beauty “devours time, money, fame, body, and soul and spits it out becoming a slave to sin and the devil” (“Il che molto è simile alla Libidine, la quale con la bellezza ci lusinga, e tira, poi ci divora, perché ci consuma il tempo, il dannaro, la fama, il corpo, e l'anima istessa ci macchia, e ci avvilisce, facendola serva del peccato, e del demonio.” (312)). This, therefore, adds an element not just of deception, but of monstrosity and of sin, bringing in a religious element as well. Lust, according to Ripa, derives in women not even solely on a sexual level but also on the pursuit of fame and money.All of this is to say that the use of emblems both had an impact on the time period’s interpretations of virtues, people, and things in the moment, as well as a longer lasting impact when the allegorical interpretation of these virtues are still seen in the present day depictions of values and morality.

Friday, September 9, 2022

New Mini-Exhibit: The Early African American Novel

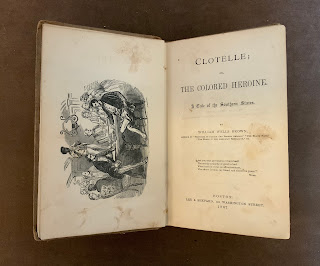

We have a new exhibit on display in our foyer: The Early African American Novel. Literature written by African American authors expanded enormously during the 19th century. Autobiographical narratives of enslavement, such as Frederick Douglass's 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave and Harriet Jacobs's 1861 Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl were particularly prominent and influential to the rhetoric of abolition.

We have a new exhibit on display in our foyer: The Early African American Novel. Literature written by African American authors expanded enormously during the 19th century. Autobiographical narratives of enslavement, such as Frederick Douglass's 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave and Harriet Jacobs's 1861 Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl were particularly prominent and influential to the rhetoric of abolition.At the same time, the African American Novel was developing. This nascent genre dealt with many of the same topics as the autobiographical narrative - such as enslavement, escape, and identity - but in a different literary medium and through a different lens. We've put together a selection of five early works by African American novelists, dating from the mid-1800s to the turn of the century, each important to the growth of that literary tradition.

Come by the Rauner this September to see the following works on display: William Wells Brown's Clotelle; or, The Colored Heroine: A Tale of the Southern States, Frank J. Webb's The Garies and Their Friends, Harriet E. Wilson's Our Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, Pauline Hopkins's Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South, and Charles W. Chestnutt's The House Behind the Cedars.

Friday, September 2, 2022

Freud and Closing Frontiers

Eighty-three years ago this month Sigmund Freud, an Austrian neurologist known globally for the foundation of psychoanalysis, died in London of oral cancer that had first appeared as a benign tumor on his jaw. Freud had been initially diagnosed with the disease in 1923, which was likely a result of his incessant cigar smoking. His earnest desire was to die in Vienna, where he had lived for most of his life after relocating there with his family at the age of four. Because of this, Freud narrowly escaped capture and confinement by the Nazis in 1938. His sons, who had previously lived in Berlin, fled to England and France in 1933, while his daughter Anna stayed in Vienna with him and his wife Martha.

Eighty-three years ago this month Sigmund Freud, an Austrian neurologist known globally for the foundation of psychoanalysis, died in London of oral cancer that had first appeared as a benign tumor on his jaw. Freud had been initially diagnosed with the disease in 1923, which was likely a result of his incessant cigar smoking. His earnest desire was to die in Vienna, where he had lived for most of his life after relocating there with his family at the age of four. Because of this, Freud narrowly escaped capture and confinement by the Nazis in 1938. His sons, who had previously lived in Berlin, fled to England and France in 1933, while his daughter Anna stayed in Vienna with him and his wife Martha.In March 1938, Hitler arrived in Vienna. Soon after, Freud's house and office were ransacked, his passport was confiscated and Anna was taken in for interrogation by the Gestapo. After a significant amount of international pressure, the Freuds were allowed to leave Austria for London in June of 1938. Four of Freud's sisters were not so lucky; unable to secure exit visas, one sister died in the Theresienstadt ghetto and the remaining three were put to death at the Treblinka extermination camp in Poland.

Rumors about the fate of the Freuds spread quickly during the initial days of the Nazi's Austrian occupation, to such an extent that Wilhelm Stekel, one of his former pupils, wrote to a Dr. L. J. London in New Hampshire to ask if he had heard the news about Freud's imprisonment. The real purpose of the letter, however, was to beg London to send him an invitation to come to New Hampshire under the pretenses of participating a medical conference. As Stekel says in his letter, "Please act as quickly as possible because frontiers could be closed at any time."

To see this letter, and correspondence from other noteworthy psychoanalysts like Carl Jung or Fritz Wittels, come to Special Collections and ask to see the L. J. London Papers (MS-1062).

Friday, August 26, 2022

Stokely Carmichael at Dartmouth

An editorial that followed sounded a bit square--concerned over Carmichael's "unfortunate tirade concerning racism," but appreciative of a new, deeper understanding of "Black Power." The bit about the "tirade" leaves us wanting to go back in time and sit with the 1,400 students. We might be more inclined to call it righteous indignation.

To read The D's reports, take a look at the November 13-15, 1966, editions. To see the amazing poster, recently donated by a member of the Class of 1969, ask for the "Lectures, 1960s" folder from the poster collection.

Friday, August 19, 2022

Ancient and Modern Apparel

De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo (Ancient and Modern Apparel of Different Parts of the World) is a seminal work in the field of fashion history, though it perhaps reveals more about the biases of its author than it does about its purported subject. Written in the 1590s by Venetian author and woodcut printer Cesare Vecellio, the treatise contains hundreds of beautifully detailed images of clothing from throughout Afro-Eurasia. During the Baroque era, one's social class, gender, and place of origin could be easily divined based on appearance and clothing. Though this was beginning to change by Vecellio's time, it was still largely true that certain people predictably dressed in a certain way. Vecellio's book was an attempt at documenting these archetypal looks from throughout the world. The treatise is also considered to be an early example of anthropology or ethnography, as Vecellio often discusses the daily habits, routines, traditions, and customs of the people whose clothes he is describing. However, Vecellio is far from a reliable source. His descriptions of foreign cultures are often filled with speculation and stereotypes. He also spends the vast majority of his book describing European dress culture, with only a very small minority of the test devoted to Africa and Asia. (A later edition of the book would also include the Americas). So while Vecellio provides the modern reader with marvelous images and interesting tidbits about dress culture, his work is perhaps best read as a glimpse into the kaleidoscope of stereotypes and tropes through which a late sixteenth century Venetian saw the world.

De gli habiti antichi et moderni di diverse parti del mondo (Ancient and Modern Apparel of Different Parts of the World) is a seminal work in the field of fashion history, though it perhaps reveals more about the biases of its author than it does about its purported subject. Written in the 1590s by Venetian author and woodcut printer Cesare Vecellio, the treatise contains hundreds of beautifully detailed images of clothing from throughout Afro-Eurasia. During the Baroque era, one's social class, gender, and place of origin could be easily divined based on appearance and clothing. Though this was beginning to change by Vecellio's time, it was still largely true that certain people predictably dressed in a certain way. Vecellio's book was an attempt at documenting these archetypal looks from throughout the world. The treatise is also considered to be an early example of anthropology or ethnography, as Vecellio often discusses the daily habits, routines, traditions, and customs of the people whose clothes he is describing. However, Vecellio is far from a reliable source. His descriptions of foreign cultures are often filled with speculation and stereotypes. He also spends the vast majority of his book describing European dress culture, with only a very small minority of the test devoted to Africa and Asia. (A later edition of the book would also include the Americas). So while Vecellio provides the modern reader with marvelous images and interesting tidbits about dress culture, his work is perhaps best read as a glimpse into the kaleidoscope of stereotypes and tropes through which a late sixteenth century Venetian saw the world. This post was originally written by Stephen Iovino '21 for Nancy Canepa's Italian 23 class, 17th and 18th Century Italian Literature.

Friday, August 12, 2022

A Poet of the Cherokee Nation

When Dewitte Duncan was nine years old, the United States government forcibly removed him, his family, and the Cherokee Nation from their ancestral lands in Georgia. The discovery of gold near Duncan's hometown of Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1828 led to the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. Over the next decade, numerous Native communities were subjected by the US authorities to what is known as the Trail of Tears, a brutal march west from the Deep South to what is now Oklahoma.

When Dewitte Duncan was nine years old, the United States government forcibly removed him, his family, and the Cherokee Nation from their ancestral lands in Georgia. The discovery of gold near Duncan's hometown of Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1828 led to the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. Over the next decade, numerous Native communities were subjected by the US authorities to what is known as the Trail of Tears, a brutal march west from the Deep South to what is now Oklahoma.Duncan survived the ordeal and, after gaining an initial education at the Cherokee Male Seminary in Tahlequah, the Cherokee Nation's new capital, he was admitted to the class of 1861 at Dartmouth College. Duncan was the oldest member of the class at the time, graduating at the age of 39, and possessed great intellectual strength and physical presence. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa and went on to be an educator in Lisbon and Littleton, New Hampshire, before returning to Oklahoma and serving as a lawyer for the Cherokee Nation. In addition to his legal acumen, he was also a prolific poet who published under his Cherokee name, Too-qua-stee.

Unfortunately, we don't have any of his works of poetry here at Rauner, but we do have an alumni file that contains more information about his life. To examine it, come visit us.

Friday, August 5, 2022

"I Don't Think Sequels Are Really Worth That Much"

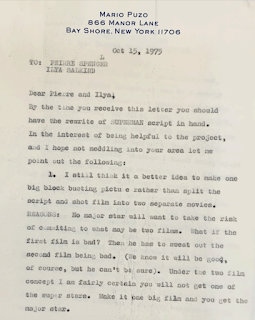

Why are we talking about this? Well, it's because of a little note we have in the papers of Mario Puzo. Puzo is best known for writing the novel The Godfather and co-writing the film trilogy that it kicked off. He also co-wrote the screenplay for DC's first major film, Superman (1978). We've touched on the writing process for the Superman screenplay before, but today let's hear what Puzo has to say on the subject of sequels and splitting up your moneymaker:

1. I still think it a better idea to make one big block busting picture rather than split the script and shot film into two separate movies. REASONS: No major star will want to take the risk of committing to what may be two films. What if the first film is bad? Then he has to sweat out the second film being bad. (We know it will be good, of course, but he can't be sure). Under the two film concept I am fairly certain you will not get one of the super stars. Make it one big film and you get the major star.

REASON # 2: At the risk of being immodest, I think the script as written can be a really blockbuster of a movies [sic] with grosses comparable to THE GODFATHER, THE STING, JAWS, THE EXORCIST. Not only because of the script but because of the built in audience which the comic book SUPERMAN has given the project. However I think being split up two movies will weaken everything, all elements of the project. You will have a lesser star, the script, any script, becomes less effective in such a situation, the shooting of the picture to be made into two becomes more complex, I would think. You save money, sure, but everything becomes more risky. Why not have an almost sure shot big hit ONE Movie rather than two risky movies?

... I think audiences are waiting for the one great big blockbuster movie. I don't think sequels are really worth that much. The sequel to the GODFATHER II is not yet out of the red. French Connection II is not really a success. And both had big big successes preceding them. If the first big Superman picture is only a mediocre success the sequel won't be worth much... Enough advice, Hope you like the script.

Superman was ultimately split into two films and cast a relative unknown, Christopher Reeve, as its star. Both Superman and Superman II were critical and commercial successes, despite Puzo's protestations. Then again, so were the Godfather movies.

To read this note and other production materials from Superman, check out MS-1371.

Friday, July 29, 2022

Revenge in the Chamber of Horrors

Whitcomb explained to his sister that Delta Alpha was “the name under which almost all the real hazing in college is done,” with each dormitory claiming its own chapter, and that this type of hazing was allowed at Dartmouth. He felt that he’d had an easy time with the hazing, describing one group of sophomores as “very nice” because they “did not make us do anything that would soil our clothes.” But the price for disobeying the upperclassmen was steep: each violation of the rules meant extra time in the Chamber of Horrors. Whitcomb didn’t say whether he knew what the Horrors in the Chamber were, but he didn’t seem too worried about it.

Whitcomb made it through his own freshman hazing, and by his senior year, he’d had plenty of opportunity to do the hazing himself. But some threats to this tradition had appeared. First, the Chamber of Horrors that year was “a pretty poor imitation of what it used to be” thanks to the faculty and Palaeopitus, who Whitcomb felt had “butted in altogether too much.” And on top of that, some freshmen were fighting back. Outnumbering the sophomores, the freshmen of Thornton Hall managed to escape their fate in the Chamber of Horrors and forced the sophomores to go through it instead. After the ensuing fight was shut down, the sophomores threatened revenge, which Whitcomb eagerly told his sister “promises to be some fun later.”

From the tone of his letters, it seems like Whitcomb was amused by the hazing and saw it as just another part of his experience at Dartmouth, but clearly, not everyone felt that way. Today, first-years live in separate housing, and Delta Alpha is a thing of the past.

To read Whitcomb’s letters, ask for MS-1438. To see more about Delta Alpha hazing, ask for the Delta Alpha vertical file.

Tuesday, July 26, 2022

Queerness in Hidden Spaces: Clifford Orr’s Influences on the Literary Sphere of Dartmouth

One hundred years ago, queer folk like Clifford “Kip” Orr, member of the class of 1922, didn’t have spaces to safely and openly write about their identities or tell stories with openly queer characters. Today, we know Orr’s sexuality because of Brendan Gill, one of Orr’s colleagues from later in his life. In his memoir Here at the New Yorker, Gill writes “Alcoholic and homosexual, Kip took terrible chances with his life, and it became a wonder that he wasn’t murdered; more than once, he was rolled, beaten up, and left for dead in some dirty doorway in the Village, and yet he survived to die sadly in the small college town where for a little while, he had known good fortune.”

While we don’t see explicit mentions of Orr’s sexuality in his papers found at Rauner, we can see two things: his manuscript for his mystery novel “The Dartmouth Murders” and the letters he wrote to his parents while a student at Dartmouth. His letters in particular tell a story about the good fortune Gill mentioned.

He also made a mark on two of the campus’s literary magazines, namely The Bema and The Dartmouth Literary Magazine, which he and two others founded together towards the end of his senior year. Orr was an official member of the literary staff of The Bema for a majority of its ninth and tenth volumes, from October 1920 to May 1922. In the Carnival number from Volume X, Bema staff showed their appreciation for Orr by nominating him to the Hall of Fame because “he is not a typical Dartmouth man,” and because “for four years he has worked quietly for the good of the college without desiring glory.” He would have served as Editor-in-Chief if not for already being president of the Dartmouth Players.

After reading these letters, it is not surprising to find that The Bema only began to publish fiction that seemed to suggest the possibility of non-normative expressions of gender and sexuality while Orr was on the magazine’s official literary staff. Volume IX of The Bema, for example, features work such as the anonymously published story “The Alley of Twilight,” which tells the story of a woman queered by her lack of interest in men. Sexuality also comes into play in one of Orr’s own pieces, “Relatives,” which tells the story of Kenneth, a student who must watch as his roommate and other fellow students rejoice during his own mother’s vaudeville performance. While this story explains Kenneth’s discomfort by the fact that the men around him are celebrating his mother, it could act as a metaphor for the experience of being uncomfortable in a room where you seem to be the only man not attracted to a woman.

Once the literary magazine began in 1922, these sorts of stories seemed to move there. Such stories include another one of Orr’s, “The Damn Fool,” where Orr embodies a non-gendered narrator writing about the death of their husband.

Unfortunately, the literary magazine only lasted for just over a year. It merged with The Bema in 1923, and even the consolidated publication left print in 1925. However, the last volume seems to be the queerest of them all. Under the supervision of Editor-in-Chief Herbert S. Talbot, who was a very frequent contributor to Orr’s literary magazine, The Bema’s last run published several stories that seem to hint at the psychological turmoil that comes with hiding one’s queerness. Talbot’s own story “The Brown-Haired Girl” is one of these stories.

So what happened? Circulation began to dwindle; they ran out of money. Did they become too controversial? Too close to queer? Also in 1925, the Dartmouth Players began casting women as the female leads, likely because of the campus conversation about whether the act of playing a female character was having an effeminizing effect on the male actors. Was that merely a coincidence? Even the archives likely won’t answer this question.

To read Orr’s letters with his parents, come in to Rauner and ask for collection MS-532, box 1.

If you’re interested in reading the fiction stories mentioned here or even in finding some more, ask for The Bema, Volumes 9 – 13, D.C. History LH1.D3 B4, and The Dartmouth Literary Magazine, D.C. History LH1.D3 D264.

Posted for Sabrina Eager '23, recipient of the Dartmouth Library's Historical Accountability Student Research Fellowship

for the 2022 Summer term. The Historical Accountability Student

Research Program provides funding for Dartmouth students to conduct

research with primary sources on a topic related to issues of

inclusivity and diversity in the college's past. For more information,

visit the program's website.

Friday, July 22, 2022

Native American Studies as Reviewed by the 1975 Evaluation Committee

This year, the Native American Studies Program, or NAS, is celebrating 50 years of operation. To honor the Program, I am exploring its history as a Historical Accountability Student Research Fellow. I should preface this blog post by stating that the NAS is different from the Native American program, or NAP. The former is an academic discipline that would become an interdisciplinary “special program” at the College, whereas the latter is a non-academic support system for Native American students.

This year, the Native American Studies Program, or NAS, is celebrating 50 years of operation. To honor the Program, I am exploring its history as a Historical Accountability Student Research Fellow. I should preface this blog post by stating that the NAS is different from the Native American program, or NAP. The former is an academic discipline that would become an interdisciplinary “special program” at the College, whereas the latter is a non-academic support system for Native American students.One of the most important parts of the NAS Program was its approval process. First, the Ad hoc Committee on American Indian Studies released a report on NAS; this was the first recommendation for such a program. After the Ad hoc Committee on American Indian Studies. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences and President Kemeny, using the recommendations from the aforementioned committee, the Committee on Instruction and Executive Committee of the Faculty, formally approved NAS on May 8, 1972.

Along with the establishment of Native American Studies, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences also approved the following: “a written evaluation be made of the academic and budgetary status of the Program, by the Committee on Instruction and by an outside team (which includes Native American scholars) appointed by the COI, during the 1975-1976 academic year, [and] such evaluation to be shared with the Executive Committee of the Faculty.”

In this blog post, I will be focusing on the written evaluation by the “outside team”, which came to be known as the Report of the Evaluation, released on March 12, 1975. In January 1975, the Evaluation Committee initially met with the goal of evaluating NAS to make a recommendation for the program. The Committee was united on all its conclusions except for the scope – regional or national – of the academic discipline. The Committee’s members included Dartmouth English Professor Peter A. Bien, Head of University of Manitoba’s Native Studies Dr. William Koolage, Dr. David Warren of the Institute of American Indian Arts, and Director of Native American Studies at the University of Montana Henrietta Whiteman.

In this blog post, I will be focusing on the written evaluation by the “outside team”, which came to be known as the Report of the Evaluation, released on March 12, 1975. In January 1975, the Evaluation Committee initially met with the goal of evaluating NAS to make a recommendation for the program. The Committee was united on all its conclusions except for the scope – regional or national – of the academic discipline. The Committee’s members included Dartmouth English Professor Peter A. Bien, Head of University of Manitoba’s Native Studies Dr. William Koolage, Dr. David Warren of the Institute of American Indian Arts, and Director of Native American Studies at the University of Montana Henrietta Whiteman. After the meetings in January, the group composed a thorough report with the following recommendations for NAS: 1) the Native American Studies continue for five more years 2) additional faculty should be hired, and the Chairman of NAS should oversee this process 3) core courses should be strengthened as additional faculty are hired 4) a language course must offered every school term. The Committee also requested that Chairman Michael Dorris be given released time for departmental consultations and meetings with the Native American community.

At this point, the interdisciplinary program is at its interim stage. When crafting the review, the Committee consulted President John G. Kemeny and the Dean of the Faculty.

The report also included a passage on why NAS was adopted at Dartmouth. Eleazar Wheelock’s original promise and the faculty’s mandate are not enough justification for the continuation of NAS. One justification for the program is the development of young adults. According to the Committee, undergraduate students are extremely curious and “their educational and vocational goals [are] not yet settled [at their age].” A second justification is because of Dartmouth’s small class size, which achieves what cannot be done at a large size university. It fosters a mutual, intimate connection between Native American and non-Native students.

The report also included a passage on why NAS was adopted at Dartmouth. Eleazar Wheelock’s original promise and the faculty’s mandate are not enough justification for the continuation of NAS. One justification for the program is the development of young adults. According to the Committee, undergraduate students are extremely curious and “their educational and vocational goals [are] not yet settled [at their age].” A second justification is because of Dartmouth’s small class size, which achieves what cannot be done at a large size university. It fosters a mutual, intimate connection between Native American and non-Native students. I find this passage notable because the narrative surrounding the Native American Studies among the student body seems to focus on Kemeny’s re-commitment to the original charter and the recruitment of Native American students. While both elements impacted NAS, Dartmouth’s uniqueness – such as its relatively small size for a private research university – allows for this academic discipline to flourish.

Posted for Farah Lindsey-Almadani '25, recipient of the Dartmouth Library's Historical Accountability Student Research Fellowship for the 2022 Summer term. The Historical Accountability Student Research Program provides funding for Dartmouth students to conduct research with primary sources on a topic related to issues of inclusivity and diversity in the college's past. For more information, visit the program's website.

Friday, July 15, 2022

A Game of Planchette

Rauner Special Collections Library is home to a wide assortment of papers related to the Cornish Colony, a New Hampshire artists' collective active through the end of World War I. Typically, we focus on the big names associated with the colony, like Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Maxfield Parrish. Today however, we're looking at an instance in the lives of the children in residence.

Rauner Special Collections Library is home to a wide assortment of papers related to the Cornish Colony, a New Hampshire artists' collective active through the end of World War I. Typically, we focus on the big names associated with the colony, like Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Maxfield Parrish. Today however, we're looking at an instance in the lives of the children in residence.In some papers belonging to Lucia Fairchild Fuller (1870-1924), a painter and member of the colony, there is a set of notes from a ouija board session she conducted with her daughter Clara and other children. Most of the answers provided by the game are next to nonsense, but one particular piece sticks out. When asked to name a set of kittens, the planchette spells out "Drown it, darn it, drat it, and damn it." It's a perfect little piece of creepiness, and apparently it stuck around. According to a note from Clara's own daughter:

'Planchette' - (or the 'Oija [sic] Board' as we call it now-) was a game loved by the children of Cornish... Lucia Fuller joined the game and the saucer rapidly named the kittens 'DROWN IT; DRAT IT; DARN IT; DAMN IT' - an event my mother (CBT) spoke of until the end of her life.

The Fairchild-Fuller family papers are full of artwork, diaries, gossipy letters, and other interesting odds and ends. To read the full notes from this game of Planchette, ask for MS-152, Box 10, Folder 41.

Friday, July 8, 2022

Exhibit: Sharing the Computer

.jpg) Looking around campus today, it is hard to believe, but there was once a time when Dartmouth didn’t have any computers. And when Dartmouth did first acquire a computer, like many institutions at the time, they faced obstacles sharing access with the Dartmouth community. It was the 1960s; computers were big and expensive, and hardly anyone knew how to use them. But when John McCarthy, a computer scientist at MIT, told Dartmouth math professor Thomas Kurtz, “you guys ought to do time-sharing,” Kurtz realized this could be the answer to Dartmouth’s problems.

Looking around campus today, it is hard to believe, but there was once a time when Dartmouth didn’t have any computers. And when Dartmouth did first acquire a computer, like many institutions at the time, they faced obstacles sharing access with the Dartmouth community. It was the 1960s; computers were big and expensive, and hardly anyone knew how to use them. But when John McCarthy, a computer scientist at MIT, told Dartmouth math professor Thomas Kurtz, “you guys ought to do time-sharing,” Kurtz realized this could be the answer to Dartmouth’s problems.To learn more about Dartmouth's innovative impact on computer science, visit the current exhibition in the Class of 1965 Galleries at Rauner Library in Webster Hall. It was curated by Val Werner '21 and is open to the public from June 28th through September 2nd during our regular hours of operation.

Friday, July 1, 2022

All Wrong, but So Right

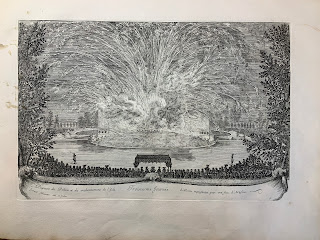

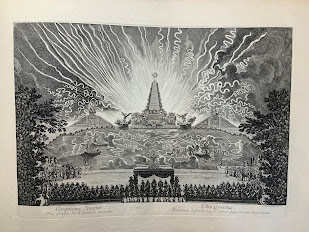

Les plaisirs de l’Isle enchantée: Course de bague; collation ornée de machines; comedie, meslée de danse et de musique; ballet du palais d’Alcine, feu d’artifice: et autres festes galantes et magnifiques (Paris: Imprimerie Royale, 1673) is a pretty amazing book. Commissioned in 1673 to document a lavish celebration of Louis XIV at Versailles, it depicts food, parties, elaborate spectacles like papier-mache sea monsters in the pools, and even the staging of one of Moliere's plays. It has all the trappings of royal extravagance and excess, and has nothing to do with a colonial rebellion. We could say featuring it this week on the blog is some kind of subtle indictment of American complacency and decadence (a party is a party), or perhaps just another example of our willingness to appropriate anything, but really, we are just into the imagery and it put us in the mood for a Fourth of July barbecue and day in the park.

Thursday, June 23, 2022

I Musk Ox You A Question

On March 17, 1917, Canadian-Icelandic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson wrote hurriedly to Sir Robert Borden, the Prime Minister of Canada. In his letter, Stefansson enclosed a small sample of wool from a musk ox, which he believed that, "if cultivated, can make Canada, continental and insular, as productive of meat, tallow and wool as the grazing regions of Australia or the Argentine."

On March 17, 1917, Canadian-Icelandic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson wrote hurriedly to Sir Robert Borden, the Prime Minister of Canada. In his letter, Stefansson enclosed a small sample of wool from a musk ox, which he believed that, "if cultivated, can make Canada, continental and insular, as productive of meat, tallow and wool as the grazing regions of Australia or the Argentine."Stefansson is clearly excited about the potential that musk ox presents to his nation: he asks Borden to set aside a half-hour for him to regale the PM with the wonders of this creature. He lists the many ways in which the reindeer in particular is an inferior creature and then boldly asserts that musk ox "will replace sheep and cattle on some ranges where these are now profitable."

To touch some musk ox wool, or to compare its texture with samples of camel hair and cashmere, come to Special Collections and ask to see the Papers of Werner Von Bergen (MSS-94).

Friday, June 17, 2022

Elementary BASIC

Have you always wanted to learn BASIC? No? Well, would you want to learn BASIC if it were taught by Sherlock Holmes? If so, we have just the book for you!

BASIC, the programming language invented at Dartmouth in the 1960s, revolutionized computing by making it easy for beginners to pick up programming for school, work, or fun. Over the following decades, methods of learning BASIC were in high demand, including at least one creative textbook. Elementary BASIC, by Henry Ledgard and Andrew Singer, resembles a typical Sherlock Holmes book, with a key difference: Sherlock is using BASIC to solve the crime. He explains it to Watson as he goes, giving examples in both BASIC and pseudo-code, such as this one for a conditional loop:

get another clue

examine the clue

until MURDERER ≠ UNKNOWN

While it may seem silly, the book covers a lot of important programming concepts. It could even be useful today if BASIC were replaced with a more modern programming language, though Elementary Python doesn't have the same ring to it.

Now that you’ve been convinced to learn BASIC, come to Rauner and ask for MS-1144 Box 10, Thomas Kurtz’s collection of BASIC texts from around the world. On June 28th, we'll also be opening our summer exhibit on the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System, which BASIC was created for.

Friday, June 10, 2022

"Feeling Great Enjoying Everything"

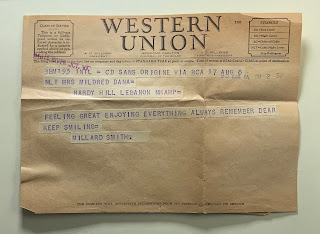

There isn't a lot of biographical information out there on Willard, but we do know that he was in his forties during World War II, with a wife and children back at home. He worked as a minister and was a practicing magician - some of his letters refer to putting on shows for local French children and to his correspondence with all his "magic friends." If his correspondence is anything to go by, he was an enormous personality and we recommend getting to know him better. Until then, we'll leave you with one of the first pieces of correspondence in the collection - a telegram that reads, in full: "Feeling great enjoying everything always remember dear keep smiling."

To read Willard's letters yourself, ask for MS-757.