“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” wrote Italian philosopher, poet, and essayist George Santayana (1863 - 1952). At Rauner Library, we often come across historical items and artifacts that speak to the reality behind Santayan’s words - demonstrating shocking parallels between current and historical events. This week, amid widespread protests, one such group of items captured our attention - John Matthew’s collection of political protest drawings and ephemera, which we previously highlighted on the Rauner blog back in 2015. Alongside political posters, student newspapers, flyers, banners, pamphlets and ephemera related to civil rights protests between 1968 and 1969, the collection also contains 23 original drawings depicting riots in Washington DC following Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April of 1968. The drawings - created by Black school children ages 8 to 16 who lived in neighborhoods most affected by the protests - strike a particular cord given their similarity to recent events unfolding in Washington D.C. and cities across the U.S. like Minneapolis and Chicago, where protestors have mobilized following the death of George Floyd.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” wrote Italian philosopher, poet, and essayist George Santayana (1863 - 1952). At Rauner Library, we often come across historical items and artifacts that speak to the reality behind Santayan’s words - demonstrating shocking parallels between current and historical events. This week, amid widespread protests, one such group of items captured our attention - John Matthew’s collection of political protest drawings and ephemera, which we previously highlighted on the Rauner blog back in 2015. Alongside political posters, student newspapers, flyers, banners, pamphlets and ephemera related to civil rights protests between 1968 and 1969, the collection also contains 23 original drawings depicting riots in Washington DC following Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April of 1968. The drawings - created by Black school children ages 8 to 16 who lived in neighborhoods most affected by the protests - strike a particular cord given their similarity to recent events unfolding in Washington D.C. and cities across the U.S. like Minneapolis and Chicago, where protestors have mobilized following the death of George Floyd.Norman W. Nickens, the assistant superintendent of D.C.’s Model School Division at the time of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, was the impetus for creating this unique record of the Washington protests as recounted through the eyes of schoolchildren. As President Lyndon B. Johnson quelled demonstrations and looting using federal troops, Nickens instructed his teachers to have the students use a variety of creative forms to express their feelings about the turmoil they’d experienced, including in-class discussions, compositions and finally - drawings.

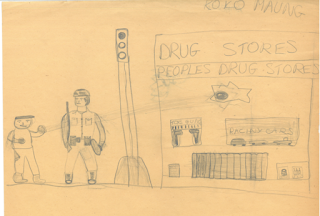

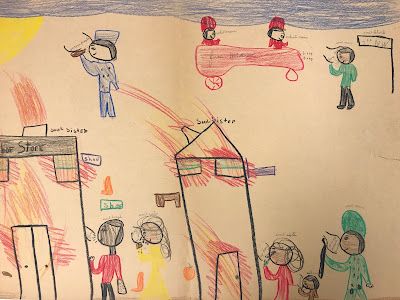

Many of the drawings depict burning buildings, ruined storefronts, and imposing crowds of helmeted federal troops amid figures with comic-strip balloons crying “help me!” or “stop!” Although some drawings focus solely on police and federal troops confronting Black protesters and others depict store looting, they all convey a sense of fear and a feeling that the world was spinning out of control. As the author of one of our drawings - a 5th grader - said at the time, “I thought the world was coming to an end… I felt like a man in a house fire.”

During what has since been called the “Holy Week Uprising” of 1968, crowds of as many as 20,000 overwhelmed Washington’s 3,100-member police force, and President Lyndon B. Johnson dispatched some 13,600 federal troops, including 1,750 federalized D.C. National Guard troops to patrol D.C.’s streets. By the time the city was considered “pacified” on Sunday, April 8, some 1,200 buildings had been burned, including over 900 stores. Across the country, over 40 protesters died and over 2,500 were injured.

During what has since been called the “Holy Week Uprising” of 1968, crowds of as many as 20,000 overwhelmed Washington’s 3,100-member police force, and President Lyndon B. Johnson dispatched some 13,600 federal troops, including 1,750 federalized D.C. National Guard troops to patrol D.C.’s streets. By the time the city was considered “pacified” on Sunday, April 8, some 1,200 buildings had been burned, including over 900 stores. Across the country, over 40 protesters died and over 2,500 were injured.

As some of the children’s drawings show, Black store owners across Washington D.C. wrote “soul brother” or “soul sister” across their storefronts so that looters would spare their stores. What did the phrase mean? To some of the interviewed children, being a soul brother or soul sister meant “being proud of being Black”, but to others - including a 7th-grader who drew one of the protest drawings - “A soul brother is a person who treats his neighbor as he would want his neighbor to treat him.” One group of Black second-graders wrote “Soul Sister” across their white English teacher’s blackboard the day after Dr. King was assassinated, even “advising her to go home early because the streets were unsafe” according to a New York Times article written by education reporter John Mathews, who had access to some of the material that had been created by the children. As the teacher recounted, her young pupils were “unusually affectionate and protective” amid the violence, having recognized her as what we would call an “ally” today- someone who stands up for others, even when they feel scared, and acknowledges and transfers the benefits of their privilege to those who lack it. These, along with many other stories of shared humanity and kindness - comprise the largely untold narrative behind an overwhelmingly violent collection of illustrations.

Despite the fact that inscribing “Soul Brother” generally provided insurance against damage, the children’s drawings also show that not all destruction was strategically planned. For instance, some of the drawings depict stores owned by white community members, engulfed in flames, with Black families living above them trapped and burned out of their own homes. Such illustrations depict the disproportionate impacts of the Holy Week Uprising felt by predominantly Black communities following the protests, despite the initial strategy of targeting white businesses.

In addition to reflecting upon their past experiences during the four days of unrest, the younger children were asked to draw pictures of their neighborhoods on Friday - the day after MLK’s assassination; on Monday - after the largest riots had occurred - and visions of what they believed it could look like in the future. The Friday scenes usually show fires, looting, and skirmishes with police, whereas the post- riot illustrations show shells of smoldering buildings, shattered windows, and militarized occupation by federal troops. Although these pre and post-riot illustrations are interesting, it is perhaps the children’s’ depictions of the future that are most illuminating… Many of these drawings depict city blocks completely transformed into a pastoral suburbia of single-family homes, with beautiful trees, families walking together, and blooming flowers.

In addition to reflecting upon their past experiences during the four days of unrest, the younger children were asked to draw pictures of their neighborhoods on Friday - the day after MLK’s assassination; on Monday - after the largest riots had occurred - and visions of what they believed it could look like in the future. The Friday scenes usually show fires, looting, and skirmishes with police, whereas the post- riot illustrations show shells of smoldering buildings, shattered windows, and militarized occupation by federal troops. Although these pre and post-riot illustrations are interesting, it is perhaps the children’s’ depictions of the future that are most illuminating… Many of these drawings depict city blocks completely transformed into a pastoral suburbia of single-family homes, with beautiful trees, families walking together, and blooming flowers.

Other pictures show the same city block, but with all the stores opened and the shelves brimming with food and supplies. These images speak to the shared hopes each of these children held for the future even amid experiencing some of the worst civil unrest during the Civil Rights movement - the desire for safety - a loving family-like community, and plentiful food and shelter. Today, although protests have taken different forms, these same desires inspire activists. The same hopes and dreams that brought thousands to the streets in 1968 still pulse in the hearts and minds of protesters today.

To view these striking snapshots of history through the eyes of the children who were living it, I encourage all those who are interested to request “MS-1335” the next time you visit Rauner Library.