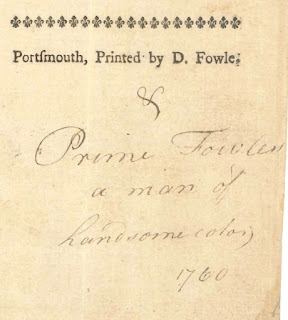

Yesterday, while pulling some 18th-century broadsides to show how the popular press functioned, we came across a curious inscription on "An Account of the Terrible Fire which Happened in Boston" from 1760. After the horrific account, the printer's name is set in type: "Portsmouth, Printed by D. Fowle." But under that, written in an 18th-century hand, is "& Prime Fowle a man of handsome color; 1760."

Yesterday, while pulling some 18th-century broadsides to show how the popular press functioned, we came across a curious inscription on "An Account of the Terrible Fire which Happened in Boston" from 1760. After the horrific account, the printer's name is set in type: "Portsmouth, Printed by D. Fowle." But under that, written in an 18th-century hand, is "& Prime Fowle a man of handsome color; 1760."Who was Prime Fowle, and why is his name added? Colonial printing is pretty well documented, so this wasn't hard to look up. Daniel Fowle established the first newspaper in colonial New Hampshire, and it turns out his pressman was his slave, Primus, also known as Prime. Primus was a well-known person in Portsmouth at the time. When he died in 1791, still a slave and disfigured from a lifetime of pulling a hand press, the local paper printed tributes and a commemorative poem in his honor.

To learn more about Primus's life, see Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage by Mark Sammons and Valerie Cunningmham (Durham: University of New Hampshire Press, 2004), pages 33-35. To see an example of his presswork, ask for Broadside 760221.