As a female student who has just finished my first year at the College, the evolution of the role of women in academia—especially at Dartmouth—is particularly fascinating to me. During my time as this summer’s Historical Accountability Student Research Fellow here at Rauner, I’m examining the stories of the very first faculty members here at Dartmouth and hope to tell their stories the way they deserve.

Hannah Croasdale was Dartmouth’s first tenured female professor, a member of the Department of Biological Sciences specializing in algae and desmids, a type of algae found in circumpolar regions. While an undergraduate and graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, she spent her summers at the Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts. The experience shaped her life in uncountable ways, and she returned to Woods Hole summer after summer to teach courses there, long before she was permitted to do so at the College. Special Collections has a photo album filled with images from her time there. This album paints a rich and exciting image of the summers that fueled a passion that easily could’ve lost its spark, given the trying nature of the career that ensued. Its pages are filled with pictures of Hannah and her friends and instructors sailing boats, collecting samples, and breaking for lunch on the beach. Underneath each photo, Hannah’s tiny script leaves a caption—sometimes the stuff of an inside joke lost to memory—and details the figures in each photo. The care that went into producing it, with each photo glued individually, shows how important it was to her that these memories be properly archived.

The book shows her attachment to it in tangible ways, too. The binding is markedly lighter than the cover, so it was likely kept on a shelf in prominent view. The edges of the pages appear burned, which could be from the fire she suffered at her Norwich home in 1989. It can be assumed, then, that the book was rescued from the fire. This photo album doesn’t just chronicle the summers she spent at Woods Hole but appears to have been a part of her entire life—some other important events it witnessed just didn’t leave a physical mark on the pages or spine.

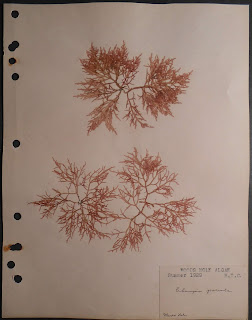

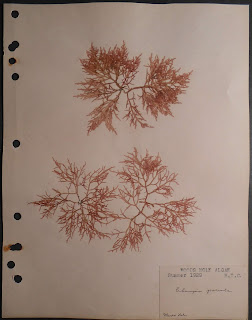

It is sometimes easy to let timelines get blurred in history, especially when looking at black-and-white images that have flattened reality into two tones. If we look at this book and then look at samples of algae collected on those trips out to sea, the hours spent laboring over this passion begin to be more fathomable. Holding samples of algae Hannah collected at Woods Hole almost 90 years ago, still impeccably preserved on the page and labeled with her familiar handwriting, makes her joy for biology as contagious now as it must have been when she taught her Phycology course at Dartmouth.

Both of these artifacts are a part of the Hannah Croasdale Papers manuscript collection, and there are hundreds of other documents, letters, Christmas cards, algae samples, slides, and photos that only begin to round out the life of an incredible educator and scientist. In the same way, combing through the entire life of this important figure, boiled down into four boxes and roughly two hundred files, feels surreal. It is noteworthy not only what she chose to keep, but also what is missing.

You can look at algae specimens Hannah collected and the rest of her manuscript collection by coming into Rauner and requesting

MS-882.

Posted for Caroline Cook '21, recipient of an Historical Accountability Student Research Fellowship for the 2018 Summer term. The Historical Accountability Student Research Program provides funding for Dartmouth students to conduct research with primary sources on a topic related to issues of inclusivity and diversity in the college's past. For more information, visit the program's website.

You all know about coloring by numbers. The numbers in the various spaces of a picture cue you into what colors to use, and in the end you get a beautiful image. What we have here is not quite the reverse of that, but still a case of using color coding to execute complicated math to arrive at a number!

You all know about coloring by numbers. The numbers in the various spaces of a picture cue you into what colors to use, and in the end you get a beautiful image. What we have here is not quite the reverse of that, but still a case of using color coding to execute complicated math to arrive at a number! This is Oliver Byrne's The First Six books of the Elements of Euclid expertly printed (and it was a tough job!) by William Pickering in 1847. Instead of letters and symbols for shapes, lines and angles, Byrne broke down Euclidean geometry into a color coded schema. Imagine the printer's patience and skill to get the registration right--probably only surpassed by the patience and skill of the reader who tried to learn geometry this way.

This is Oliver Byrne's The First Six books of the Elements of Euclid expertly printed (and it was a tough job!) by William Pickering in 1847. Instead of letters and symbols for shapes, lines and angles, Byrne broke down Euclidean geometry into a color coded schema. Imagine the printer's patience and skill to get the registration right--probably only surpassed by the patience and skill of the reader who tried to learn geometry this way.