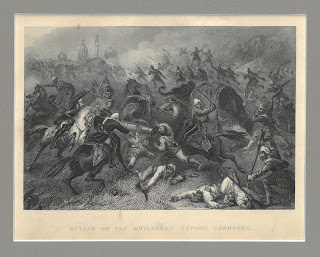

It is indeed shocking to see the three large boxes brought up from the depths of Rauner. Once opened, the volume of the content engages you. 78 matted and shrink-wrapped engravings stored tightly like files in their separate boxes invite you to pick one up, then the next. The first may be a dramatic battle scene with combatants on horseback being thrust into the air or dramatically slain in the center of the scene with a full-fledged, incredibly detailed war in action in the background. You look closer and are impressed with the curve and shadow on the horse’s neck, and the telling facial expression on the main subject’s face. This is due to the fine detailing of the steel engraving process. You can see the fear in his eyes and the concentration in his muscle movement.

It is indeed shocking to see the three large boxes brought up from the depths of Rauner. Once opened, the volume of the content engages you. 78 matted and shrink-wrapped engravings stored tightly like files in their separate boxes invite you to pick one up, then the next. The first may be a dramatic battle scene with combatants on horseback being thrust into the air or dramatically slain in the center of the scene with a full-fledged, incredibly detailed war in action in the background. You look closer and are impressed with the curve and shadow on the horse’s neck, and the telling facial expression on the main subject’s face. This is due to the fine detailing of the steel engraving process. You can see the fear in his eyes and the concentration in his muscle movement. The next engravings are wildly different; a house with many windows and four nicely nurtured trees evenly spaced outside the front. More show ‘the capture of the king of Delhi’, the ‘blowing up of the cashmere gate at Delhi’, ‘Miss. Wheeler defending herself against the Sepoys at Cawnpore’ and the ‘outlying picket of the highland brigade at Benares’- a chilling image of cannons, soldiers and animals in the foreground with seven naked bodies hung from a branch in the background. Other than these theatrical action scenes, there are also images of locations, portraits of important figures, and two colorful, beautifully drawn maps relevant to the Sepoy Rebellion.

The next engravings are wildly different; a house with many windows and four nicely nurtured trees evenly spaced outside the front. More show ‘the capture of the king of Delhi’, the ‘blowing up of the cashmere gate at Delhi’, ‘Miss. Wheeler defending herself against the Sepoys at Cawnpore’ and the ‘outlying picket of the highland brigade at Benares’- a chilling image of cannons, soldiers and animals in the foreground with seven naked bodies hung from a branch in the background. Other than these theatrical action scenes, there are also images of locations, portraits of important figures, and two colorful, beautifully drawn maps relevant to the Sepoy Rebellion.These engravings are part of Charles Ball’s British jingoistic retelling of the Sepoy Rebellion. Ball – a 19th century acclaimed British historian – wrote a seven part history detailing the Rebellion. The parts were issued separately from the maps and engravings with the intention that buyers would purchase them all and bind them into two separate volumes. His ‘histories’ of the rebellion many times depict popular rumors as fact and endeavor to render Indians as inferior and savage and British as courageous and triumphant.

The engravings, maps and books are now collector’s items, sold from relatively high-end auction houses. Our set of engravings was given by Wayne Broehl in 1994, who also donated other material related to wars particularly in Japan and India. He was a member of the Tuck School faculty and he also wrote a book called The Crisis of the Raj on the Sepoy Rebellion, which is available in Dartmouth’s libraries today.

Ball’s engravings have been used in many retellings, articles, scholarly journals, books and essays as media supplement to text about the Rebellion and this time period in India. His recounting of these events were of the first colonialist interpretations of 1857, revealing much about British attitude towards the Sepoy Rebellion and racist sentiments of the time.

To see the engravings, ask for MS-790. The shrink wrap is not a good idea from an archival standpoint, so we will be removing it!

Posted for Sophia Linkas '21