“Like men, do women not have a rational soul? Why then shall they not enjoy the privilege of the enlightenment of letters? Is a woman’s soul not as receptive to God’s grace and glory as a man’s? Then why is she not able to receive learning and knowledge, which are the lesser gifts? What divine revelation, what regulation of the Church, what rule of reason framed for us such a severe law?”

“Like men, do women not have a rational soul? Why then shall they not enjoy the privilege of the enlightenment of letters? Is a woman’s soul not as receptive to God’s grace and glory as a man’s? Then why is she not able to receive learning and knowledge, which are the lesser gifts? What divine revelation, what regulation of the Church, what rule of reason framed for us such a severe law?”

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a seventeenth-century nun, self-taught scholar and acclaimed writer of the Latin American colonial period and the Hispanic Baroque penned this reproach in a letter to the Bishop of Puebla in 1690. In this letter, she defended and ardently advocated for the right of women to education and intellectual pursuits. Sor Juana spent most of her life in Mexico City, the heart of the autocratic and theocratic viceroyalty of New Spain. Her uncompromising stance on the issue of women’s rights is remarkable when considering that women’s subordination to men and the Church was almost absolute in colonial Spanish America.

As literary translator Alan S. Trueblood stated in his introduction to A Sor Juana Anthology, “Of all the memorable Hispanic voices of the later half of the seventeenth century—and they were not lacking in those dominions on which the sun never set—Sor Juana most clearly pierces constraints to proclaim the will and the right of the individual—and particularly of the individual woman—to realize herself intellectually, artistically, and emotionally.”

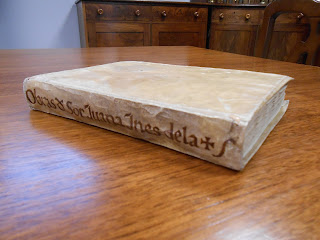

Sor Juana is celebrated in many intellectual circles today as the “First Feminist of the New World.” At Rauner, we have the first publication of Sor Juana’s poetry, a volume grandly called the Inundación castálida de la única poetisa, Musa Décima, sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (The Overflowing of the Castalian Spring, by the Singular Poetess, Tenth Muse, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz), published in Madrid in 1689.

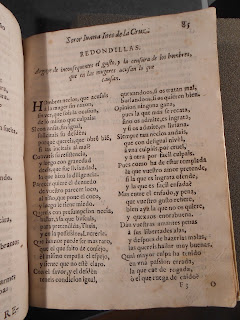

Sor Juana’s poetry chronicles the rigid gender relations and double standards that pervaded seventeenth century society. Recurrent themes include love and indiscretion, individual honor, and, her favorite dichotomy, female vanity versus female intellect. Her ideological stance on women’s rights is nowhere clearer than in her most famous redondilla that begins “Hombres necios que acusáis.” This philosophical satire is an indictment that criticizes men for manipulating women, and reprimands women for their passivity and submission to men. The redondilla begins with three powerful stanzas:

Silly, you men—so very adept

at wrongly faulting womankind,

not seeing you’re alone to blame

for faults you plant in woman’s mind.

After you’ve won by urgent plea

the right to tarnish her good name,

you still expect her to behave—

you, that coaxed her into shame.

You batter her resistance down,

and then, all righteousness, proclaim

that feminine frivolity,

not your persistence, is to blame.