Never has a text seemed more relevant than this particular one does today. Entitled "A Secret Worth Knowing: A Treatise on the Most Important Subject in the World, Simply to Say, Insanity," this 95-page pamphlet was written by Green Grimes, an inmate of the Lunatic Asylum of Tennessee in 1846. In this fascinating little book, Grimes recounts his experiences that led to what must have been a psychotic break. After his father remarried when Grimes was fourteen, his older brother, Grimes's only confidant and protector, was driven away from the house by the new wife. On the brother's journey to his new apprenticeship with a local parson, he drowned while crossing a river. This initial trauma was followed by many other significant events which ultimately led to Grimes's breakdown and admittance to the insane asylum. In the introduction, Grimes notes that his goal for writing this book is twofold: to be a practical resource for others and to raise a small amount of money to provide for his five orphaned children.

After recounting his own story, Grimes goes on to describes many examples of insanity that he has

encountered or heard about during his lifetime, delineates the process by which people go insane, and then takes great pains to differentiate between insanity and "idiotism." Throughout his work, he attempts to encourage his readers who have family members suffering from mental illness by providing advice about how to care for and watch over their loved ones. Finally, he concludes by saying, "There is, perhaps, nothing short of the goodness of God that can effect a final cure of my disease. I am perfectly resigned to His will, and await his final coming and decision with hope."

To examine this subject, please come to Rauner and ask for Rare RC464 .G756 1846.

Friday, November 11, 2016

Tuesday, November 8, 2016

One War, Different Stories

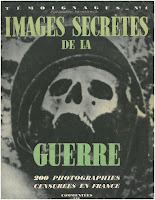

As I was looking for materials for a session with the World War I history course, I found this serial publication in our Rare Book Collections. Témoignages de notre temps is a compilation of about 200 photographs taken during World War I which had been censured by the French government during the war. Produced by the "Société Anonyme les Illustrés Français," this is the first issue of the bi-monthly serial. The photographs have come from various entities in different countries across Europe, ranging from an archive to an individual who fought in the war. The preface notes that these photos were originally taken for the purpose of documenting the reality of the war. The anonymous editors urge the readers to see beyond the heroic and glorious image of war that the French government had publicized. According to the preface, one of the editors worked for the French government's censorship department during the war, which allowed a certain level of access to many of the censored photos and documents. However, in most cases, attempts to publish these materials were frustrated as the French government was still reluctant to make them available for public even after more than a decade.

As I was looking for materials for a session with the World War I history course, I found this serial publication in our Rare Book Collections. Témoignages de notre temps is a compilation of about 200 photographs taken during World War I which had been censured by the French government during the war. Produced by the "Société Anonyme les Illustrés Français," this is the first issue of the bi-monthly serial. The photographs have come from various entities in different countries across Europe, ranging from an archive to an individual who fought in the war. The preface notes that these photos were originally taken for the purpose of documenting the reality of the war. The anonymous editors urge the readers to see beyond the heroic and glorious image of war that the French government had publicized. According to the preface, one of the editors worked for the French government's censorship department during the war, which allowed a certain level of access to many of the censored photos and documents. However, in most cases, attempts to publish these materials were frustrated as the French government was still reluctant to make them available for public even after more than a decade.The magazine is divided into different chapters which attempts to debunk myths on specific aspects of the war that the French government had created through its censorship. Though it would be great to take a look at them in this post, some of the photos were just too gory (for instance, a trench full of ripped apart cadavers) so I have intentionally excluded them from this post.

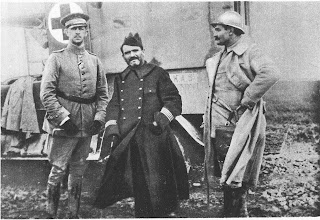

In the first chapter, the magazine dispels the myth that the French and German soldiers on the front held a deeply-rooted hatred towards one another. Like in these photos, French and German generals stand side by side to chill or visit an injured soldier together.

Though it was strictly forbidden for soldiers from the Allies and the Axis powers to force prisoner to contribute to their military efforts, it was not rare to spot German prisoners of war working in a French munition factory or vice versa.

Another type of frequently censored photograph were those of the soldiers from the French North African colonies. The French government did not want to give an impression that the African soldiers were part of the war efforts, especially on the front.

The magazine continues to break down the binary of the devil German and the righteous Allies by showing more humane side of the enemies. Rather than being tortured by atrocious German prison keepers, the British prisoners of war play cricket in the German prison camp.

African prisoners of the war casually cruise down the streets of Berlin.

The wartime press coverage of Paris often times hid the ugly aspects of the reality to convince people that France was in good shape. But these photos tell the story of wartime Paris that the government strove to hide.

Parisians were not always as poised as the government portrayed them to be. They ransacked stores with foreign-sounding names, though most of them were businesses operated by French citizens.

Though the government would have hated to admit it, the Parisians also suffered from bomb strikes and shortage of food supplies.

The rest of the chapters explain Axis propaganda; marine warfare (it was the first war that submarines were used for military purpose); and the arts of espionage.

Reading this serial publication made me wonder what was the contemporary public's reaction to these photos. Would they have been appalled that the government had been hiding some aspects of the war? Or maybe, it already was not so much of a "secret" despite the government's efforts to make them so.

To look at the publication yourself, ask for Rare Book D501 .T46 No. 1 1933:Mai in our reading room.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)