The history of the best known engraving of Dartmouth College--how it came about, and the life of the artist who created it--is one of the more unusual tales in American print history.

Christian Meadows (1814-after 1872) was an engraver who immigrated to Boston from England in the 1830s. In early 1849, Meadows was working for W. W. Wilson of Boston, engraving plates for bank notes and dies for stamping coins. He disappeared about the same time some plates for printing bank notes were stolen from the firm. In March of that year, Meadows appeared in Wells River, Vermont, in the company of his wife, the burglar and bank robber William "Bristol Bill" Warburton, and Margaret O'Connell, a Boston counterfeiter. Meadows was suspected of passing counterfeit notes at a Wells River bank, and a search of the group's Groton, Vermont, house revealed burglar's tools, a printing press, and some of the engraved bank note plates that had been stolen from W. W. Wilson. Meadows was arrested, tried for counterfeiting, convicted, and sentenced to ten years at the Vermont State Prison in Windsor beginning in June, 1850. The story of the breaking of this counterfeiting ring was sensational enough to be carried in newspapers from as far west as Wisconsin.

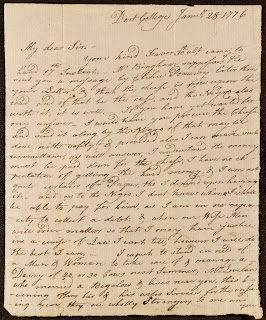

The following year, three Dartmouth students--E.T. Quinby, George W. Gardner, and Charles Caverno--planned to commission an engraving of the College. The trio went to Boston in search of an engraver and learned that New England's finest engraver was imprisoned at Windsor. They asked Warden Henry Harlow to permit Meadows to work on the project. Meadows must have been a model prisoner, for Harlow allowed him to travel from Windsor to the Dartmouth campus under guard to make drawings for the engraving. Upon returning to the prison, Meadows engraved the copper plate for the print.

Meadows chose a view looking south from near the present site of Rollins Chapel to depict Wentworth Hall, Dartmouth Hall, Thornton Hall, and the whitewashed Reed Hall. The three-and-a-half story brick Dartmouth Hotel can be glimpsed through trees at the right opposite the common which is bordered by fences and crisscrossed by paths. The prominent elm in the foreground recalls the tree's popularity as an ornamental, and saplings protected by tree boxes to prevent hitched horses from damaging their trunks flank the elm and are planted around the common. Meadows' view projects order and serenity--qualities that he seems to have been unable to integrate into his life up to that time.

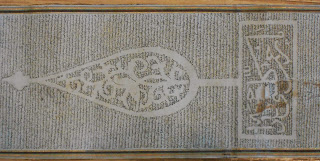

The print was seen by Dr. John Walker of the New Hampshire Agricultural Society who offered the jailed engraver the job of producing the Society's diploma to be awarded at the annual agricultural fair. A pastoral drawing by portrait painter Daniel G. Lamont who was then living near Daniel Webster's birthplace in Franklin, New Hampshire, was incorporated into the final image by Meadows. A copy of the engraved diploma was sent to Webster who was Secretary of State in the Fillmore administration. Upon seeing it, Webster remarked: "Who is the engraver that has done this? Where does he dwell? I have been searching for such a man. We want him at the State Department to engrave Maps."

Webster asked Vermont Governor Charles K. Williams to pardon Meadows, asking "Why do you bury your best talents in your state prisons?" The Governor declined, and a year later Webster was dead. A new Governor, Erastus Fairbanks, issued the pardon probably out of respect for Webster and his earlier effort. Meadows was freed on July 4, 1853, and he remained in Windsor until 1859 making engravings of education institutions including Appleton Academy in New Ipswich, New Hampshire, and Vermont's Thetford Academy. Meadows moved to Buffalo, New York, the following year where he worked as an engraver, he was listed under the same occupation in Toronto city directories for 1871 and 1872, and then he disappears from the record.

To see engravings made by Meadows in and out of prison, ask for Iconography

72,

416,

735,

Broadside f852590, and

f862626.

Posted for Richard Miller

By the time 1582 rolled around, the Julian calendar was no longer accurate and the refined Gregorian calendar was slated to become the daily planner of choice. Great Britain obviously thought that this required further study and waited until 1751 to pass an act "regulating the Commencement of the Year, and correcting the calendar now in use." In order to prevent widespread confusion and panic, the act decreed that January would become the "first month of the year 1752." Prior to this March had been the usual start of the new year.

By the time 1582 rolled around, the Julian calendar was no longer accurate and the refined Gregorian calendar was slated to become the daily planner of choice. Great Britain obviously thought that this required further study and waited until 1751 to pass an act "regulating the Commencement of the Year, and correcting the calendar now in use." In order to prevent widespread confusion and panic, the act decreed that January would become the "first month of the year 1752." Prior to this March had been the usual start of the new year.