In July of 1879, the USS Jeannette left San Francisco and headed for the Bering Strait, intent on reaching the North Pole. The expedition was betting on the proposition that the warm water currents off the coast of Japan would carry them north through the strait and into an Open Polar Sea (a soon-to-be debunked theory of ice-free waters surrounding the Pole). This ambitious trip was rather disastrous, as the Jeannette became stuck in pack ice in September and drifted on until it was finally crushed by the pressure of the ice in June of 1881. The crew then took to sledges and whaleboats, attempting to travel through the ice to the Siberian coast. Of the 33 men taking part in the expedition, only 13 survived to return to the U.S.

In July of 1879, the USS Jeannette left San Francisco and headed for the Bering Strait, intent on reaching the North Pole. The expedition was betting on the proposition that the warm water currents off the coast of Japan would carry them north through the strait and into an Open Polar Sea (a soon-to-be debunked theory of ice-free waters surrounding the Pole). This ambitious trip was rather disastrous, as the Jeannette became stuck in pack ice in September and drifted on until it was finally crushed by the pressure of the ice in June of 1881. The crew then took to sledges and whaleboats, attempting to travel through the ice to the Siberian coast. Of the 33 men taking part in the expedition, only 13 survived to return to the U.S.This is not the story of how the Jeannette survivors were rescued. Instead, it is the story of an expedition that didn't even come close to rescuing them. By 1881, there was worry enough regarding the Jeannette's disappearance that two Navy ships were dispatched to search for the crew. The USS Rodgers was sent on the same path the Jeannette took: through the Bering Strait. In a supremely unlucky turn of events, the ship was destroyed by a fire and the rescue crew themselves had to be saved.

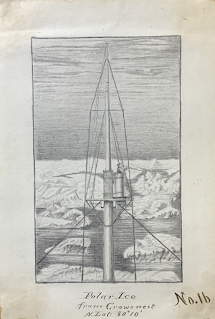

Meanwhile, the USS Alliance was sent to look on the other side of the North American continent between Iceland, Norway, and Svalbard. Although that was over 4,000 miles from where the Jeannette actually ended up, there was arguably a chance that the ship had made it over the top of the continent and come out on the other side. Whether or not this was ever a real possibility, the newspaperman James Gordon Bennett Jr., who had funded the Jeannette expedition, pushed hard for the secondary search to be made. He also took steps to ensure he'd get the scoop on any resulting news. He placed a reporter on board the Alliance and requested photographs from the trip. A camera could not be acquired in time for the ship's departure and so one of the crew members made a series of sketches instead.

And this is what brings us to today's piece of the collections, if you'll forgive the long prologue. Jefferson Brown, an assistant engineer on the Alliance, made a series of about thirty (surviving) sketches along the way, documenting icy landscapes, shipwrecks, polar bears, and more. Some were reproduced in print later when Brown had his own account of the trip published, but others appear to exist only within this disbound sketchbook carried all around the Northernmost waters of the Atlantic Ocean in 1881. The Alliance wouldn't find any trace of the doomed Jeannette expedition, but its crew would see a part of the world that the United States had shown little interest in up to that point. They collected data on water currents and temperatures, specimens of regional flora and fauna, and observations on phenomena ranging from the movement of pack ice to the Northern Lights. It wasn't much of a rescue mission, but if Brown's work is anything to go by, it must have been quite the trip.

To see Brown's sketches and read his account of the Alliance's journey, ask for Stefansson Mss-184.

No comments:

Post a Comment