"I am a radical feminist, there is no doubt about it." - Professor Marysa Navarro, 11/2/1981 interview with The Dartmouth

"I am a radical feminist, there is no doubt about it." - Professor Marysa Navarro, 11/2/1981 interview with The DartmouthTraditions are typically celebrated at Dartmouth, and Ivy League institutions are renowned for their rich history, traditions, and culture. The Dartmouth of today is an ever-changing place, with the school becoming increasingly diverse in race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic class. However, there was a time when questioning traditions at Dartmouth was much more taboo. Throughout most of Dartmouth's history up to the 1960s, Dartmouth was an almost all-white, all-male university to which most of the American population likely never had access. It came as a shock to me when I discovered that one of the first women to receive tenure at Dartmouth, Latin American History Professor Marysa Navarro Aranguren, was also a Hispanic immigrant. given our shared Hispanic identity, along with having experienced the immigrant perspective from the third person perspective through my parents, I was immediately interested in studying her life and career at Dartmouth.

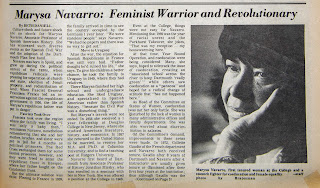

Navarro was born in Pamplona, Spain on October 12, 1934. Navarro painted a portrait of a 20th-century Hispanic intellectual, a feminist, an activist, and a professor, despite living and teaching in an overwhelmingly white space. in a 1975 interview with The Dartmouth, Navarro spoke about her childhood and life before Dartmouth. She was born to a republican Spanish family who was forced to flee their home after the Fascist takeover of Spain while she was a baby. First, the Navarro family moved to France, but after it was taken over by the Germans during WWII, they found themselves stateless. As a result, the family finally decided to move to Uruguay, where Navarro finished her high school and her undergraduate education. Afterward, Navarro was able to complete a fellowship at Douglas College in New Jersey, and eventually married and completed her master's and doctorate degrees at Columbia University. Her decision to study Spanish American history over Spanish history stems from the fact that she thought the Spanish civil war was "too traumatic to study." Her upbringing and violent childhood inspired much of her beliefs, decisions, and political activism later in her life.

Navarro was born in Pamplona, Spain on October 12, 1934. Navarro painted a portrait of a 20th-century Hispanic intellectual, a feminist, an activist, and a professor, despite living and teaching in an overwhelmingly white space. in a 1975 interview with The Dartmouth, Navarro spoke about her childhood and life before Dartmouth. She was born to a republican Spanish family who was forced to flee their home after the Fascist takeover of Spain while she was a baby. First, the Navarro family moved to France, but after it was taken over by the Germans during WWII, they found themselves stateless. As a result, the family finally decided to move to Uruguay, where Navarro finished her high school and her undergraduate education. Afterward, Navarro was able to complete a fellowship at Douglas College in New Jersey, and eventually married and completed her master's and doctorate degrees at Columbia University. Her decision to study Spanish American history over Spanish history stems from the fact that she thought the Spanish civil war was "too traumatic to study." Her upbringing and violent childhood inspired much of her beliefs, decisions, and political activism later in her life.

No comments:

Post a Comment