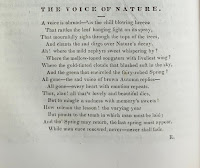

This post compares "The Voice of Nature," a poem printed in an 1840 issue of the Dartmouth student newspaper (The Dartmouth), with an excerpt from "Thanatopsis" written by William Cullen Bryant in 1817:

Both “The Voice of Nature” and William Cullen Bryant’s “Thanatopsis” present models for understanding the inescapability of death – that every man will enter “the great tomb of man” (Bryant) “in which man must be laid” (The Dartmouth). But the poems differ in their response to the inevitable – where “The Voice of Nature” responds to death with the hope of the resurrection: “man once renewed never – never shall fade,” “Thanatopsis” restates that man will always remain dead in “thine eternal resting-place,” “in their last sleep,” and “each shall take / His chamber in the silent halls of death.” By implication, “The Voice of Nature” invokes a more Judeo-Christian model of death’s impermanence and the promise of renewal, whereas “Thanatopsis” responds with a more stoic approach to death’s permanence: “So live… by an unfaltering trust” and “approach thy grave.”

The effectiveness of “The Voice of Nature” comes through the parallelism of seasonal change in nature with the Christian message: autumnal decay (man’s life as a sinner), winter’s death (man’s death), and spring’s rebirth (man’s renewal); for the sadness of autumn and winter mirror man’s death, if not for the promise of spring. The “sighs,” “the sad dirge” the questions of “where…? Where…? Where…?” and “the sad voice” answering “All gone” setup the “The Voice of Nature’s” “lesson”; for the sadness of winter indeed “points to the tomb” but that one day “the last spring must appear” and the seasons of life will be no more. On the other hand, the effectiveness of “Thanatopsis” comes through its application and subsequent pacification of autophobic fears of being forgotten: “what if… no friend take note of thy departure” and “The gay will laugh when thou art gone”; and to pacify those fears, the poem equalizes all mankind: “kings, The powerful of the earth - the wise, the good…All in one mighty sepulchre,” “matron and maid, the speechless babe, and the gray-headed man - Shall one by one be gathered to thy side.”

Written by a member of the class of 2021

Excerpt from "Thanatopsis" by William Cullen Bryant

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Both “The Voice of Nature” and William Cullen Bryant’s “Thanatopsis” present models for understanding the inescapability of death – that every man will enter “the great tomb of man” (Bryant) “in which man must be laid” (The Dartmouth). But the poems differ in their response to the inevitable – where “The Voice of Nature” responds to death with the hope of the resurrection: “man once renewed never – never shall fade,” “Thanatopsis” restates that man will always remain dead in “thine eternal resting-place,” “in their last sleep,” and “each shall take / His chamber in the silent halls of death.” By implication, “The Voice of Nature” invokes a more Judeo-Christian model of death’s impermanence and the promise of renewal, whereas “Thanatopsis” responds with a more stoic approach to death’s permanence: “So live… by an unfaltering trust” and “approach thy grave.”

The effectiveness of “The Voice of Nature” comes through the parallelism of seasonal change in nature with the Christian message: autumnal decay (man’s life as a sinner), winter’s death (man’s death), and spring’s rebirth (man’s renewal); for the sadness of autumn and winter mirror man’s death, if not for the promise of spring. The “sighs,” “the sad dirge” the questions of “where…? Where…? Where…?” and “the sad voice” answering “All gone” setup the “The Voice of Nature’s” “lesson”; for the sadness of winter indeed “points to the tomb” but that one day “the last spring must appear” and the seasons of life will be no more. On the other hand, the effectiveness of “Thanatopsis” comes through its application and subsequent pacification of autophobic fears of being forgotten: “what if… no friend take note of thy departure” and “The gay will laugh when thou art gone”; and to pacify those fears, the poem equalizes all mankind: “kings, The powerful of the earth - the wise, the good…All in one mighty sepulchre,” “matron and maid, the speechless babe, and the gray-headed man - Shall one by one be gathered to thy side.”

By effect, both “The Voice of Nature” and “Thanatopsis” build the emotional stake within the poem in order to respond to a more realized feeling: the build – “all that's lovely and beautiful dies” (The Dartmouth) and “So shalt thou rest… all that breath will share thy destiny” (Bryant); and the response – “man once renewed never – never shall fade” (The Dartmouth) and “So live” (Bryant). Even though “Thanatopsis” and “The Voice of Nature” were published within twenty-three years of each other and focus on similar themes, each presents a unique response to death’s authority and by their distinctions could illustrate fashionable divisions and conceptions of the afterlife in the early nineteenth-century.

Written by a member of the class of 2021

Excerpt from "Thanatopsis" by William Cullen Bryant

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills

Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun,—the vales

Stretching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods—rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, poured round all,

Old Ocean’s gray and melancholy waste,—

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death,

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom.—Take the wings

Of morning, pierce the Barcan wilderness,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings—yet the dead are there:

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep—the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest, and what if thou withdraw

In silence from the living, and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one as before will chase

His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glide away, the sons of men,

The youth in life’s green spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron and maid,

The speechless babe, and the gray-headed man—

Shall one by one be gathered to thy side,

By those, who in their turn shall follow them.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

No comments:

Post a Comment