Tucked into the pages of his cumbersome and crumbling “mem book,” which now resides in the Rauner Special Collections Library, lies Francis Gilman Blake’s hand-drawn map of an expedition through the New Hampshire wilderness, annotated with the details of each day’s travel and a branch plucked from the slopes of Mt. Washington. While the practice of scrap-booking at Dartmouth has since been replaced by other hobbies and interests, the Rauner Library has preserved some of the books created by students from the early twentieth century.

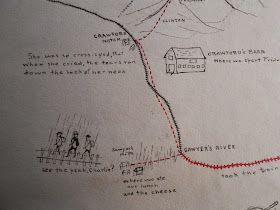

Tucked into the pages of his cumbersome and crumbling “mem book,” which now resides in the Rauner Special Collections Library, lies Francis Gilman Blake’s hand-drawn map of an expedition through the New Hampshire wilderness, annotated with the details of each day’s travel and a branch plucked from the slopes of Mt. Washington. While the practice of scrap-booking at Dartmouth has since been replaced by other hobbies and interests, the Rauner Library has preserved some of the books created by students from the early twentieth century. Although simplistic in their detail, Blake’s illustrations of the mountains prove stunningly accurate in their physical relationship to each other. The mountains are carefully spaced and aligned, yet they are not drawn from a bird’s-eye view like a traditional map, but from a perspective on the horizon, evoking a deeply personal recollection of the landscape. In terms of geographic orientation however, Blake only offers his audience a single winding line through a series of mountains and towns. But to someone familiar with the mountains, trails, and roads of the region, Blake’s map tells an incredibly vivid and personal story of adventure. The map therefore serves not as a geographical tool, but as an experiential guide. In terms of absolute place and geography it is meaningless, but as a relative measure of place within a shared context, it tells a story more detailed and intimate than any cartographer could draft.

Although simplistic in their detail, Blake’s illustrations of the mountains prove stunningly accurate in their physical relationship to each other. The mountains are carefully spaced and aligned, yet they are not drawn from a bird’s-eye view like a traditional map, but from a perspective on the horizon, evoking a deeply personal recollection of the landscape. In terms of geographic orientation however, Blake only offers his audience a single winding line through a series of mountains and towns. But to someone familiar with the mountains, trails, and roads of the region, Blake’s map tells an incredibly vivid and personal story of adventure. The map therefore serves not as a geographical tool, but as an experiential guide. In terms of absolute place and geography it is meaningless, but as a relative measure of place within a shared context, it tells a story more detailed and intimate than any cartographer could draft.While miles and locations ordinarily serve as measures of distance and place, juxtaposed in this context they convey a measurement of relative time. Blake’s itinerary provides a list of the mountains and mileage that tells not only of where he went, but also of the fast pace and strenuous nature of the hike, allowing those familiar with these steep slopes an intimate perspective on the passing of the journey. Over one hundred years later, these chronological clues prove much more valuable than the dates that accompany them. Notions of absolute time have become lost over the decades, but Blake has preserved these episodes by grounding them in a relative context that survives today.

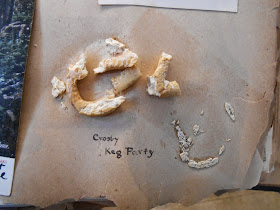

Blake’s book ends at over one hundred pages, weighs as much as a large dictionary, and holds various large objects between its pages including entire flowers, small books, and notably a 108 year-old pretzel. These characteristics suggest that Blake never intended this book to travel, or even to be opened on a regular basis. Without a title page, cohesive structure, or labels for many of the photographs, Blake’s intended audience likely comprises a small group of those quite familiar to him and his experiences. This conclusion, drawn from the physical nature of the book, is supported by his uses of time and place within a shared context. Perhaps the chief member of Blake’s audience is his future self, the individual best equipped to unravel the relative contexts of his maps. Blake’s audience is limited only by a reader’s willingness and ability to engage these objects outside of their absolute geographical and chronological contexts, the depth of the connection determined by the extent of the shared experience.

Posted for Edward Harvey '15

No comments:

Post a Comment