These are among the imaginative claims made in an editorial in the Connecticut Courant, which was then highlighted in the September 15, 1800, edition of the Dartmouth Gazette. Not only did Moses Davis, the publisher of the Gazette, choose to include this article in his newspaper shortly before the election of 1800, but he printed this harangue against Thomas Jefferson on the front page. Burleigh, the author of the piece, further reveals his Federalist leanings by stressing the turmoil during the time of the Confederation. He claims it was a system to which Jefferson desired to return. He also disparages Jefferson's sympathies with France, and presents a glaring contrast between Jefferson and "the Great Man," President Washington. In 1777, the Continental Congress created the Articles of Confederation, which the thirteen original states all ratified by 1781. The Articles intentionally did not establish a strong centralized government, and when it became apparent that this system was inadequate to govern the nation, it was replaced by that crafted under the Constitution, which was collectively ratified by 1789.

Why were Burleigh and Davis interested in publishing an article against Jefferson that seems almost ridiculous to readers today? Clearly Burleigh was determined to paint a negative picture of this Republican candidate, and he had reason to be concerned. In the election of 1800 the Republicans, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, defeated the top Federalist candidate and incumbent, John Adams, finally breaking twelve years of Federalist reign. Despite the outcome of the election, Burleigh's piece reveals how the press had an important role in the developing political sphere of the early Republic. Without televised debates, political phone calls, or flashy bumper stickers, political deliberation often played out in writing. Newspapers were especially influential because they could make words both permanent and available to various people and communities. Davis's decision to feature Burleigh's article shows the political leanings of his readers—his goal was to sell newspapers after all, not merely to spread outrage.

Why were Burleigh and Davis interested in publishing an article against Jefferson that seems almost ridiculous to readers today? Clearly Burleigh was determined to paint a negative picture of this Republican candidate, and he had reason to be concerned. In the election of 1800 the Republicans, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, defeated the top Federalist candidate and incumbent, John Adams, finally breaking twelve years of Federalist reign. Despite the outcome of the election, Burleigh's piece reveals how the press had an important role in the developing political sphere of the early Republic. Without televised debates, political phone calls, or flashy bumper stickers, political deliberation often played out in writing. Newspapers were especially influential because they could make words both permanent and available to various people and communities. Davis's decision to feature Burleigh's article shows the political leanings of his readers—his goal was to sell newspapers after all, not merely to spread outrage.But this election is also notable because it initially resulted in a tie, with Republicans Jefferson and Burr both receiving 73 electoral votes, and Federalists John Adams and C. C. Pinckney winning 65 and 64 electoral votes respectively. Since this was before Presidents and Vice Presidents came as a package deal as running mates, whichever candidate won the most votes would be declared President, and whoever came in second would become their VP. Due to the tie, the decision fell into the hands the House of Representatives, who would then vote as states. Ironically, thanks to the previous administrations, the House was filled with the Federalists, so neither Jefferson nor Burr was the Congressmen's first choice. It therefore took numerous (35 to be exact) votes to finally achieve a majority and elect the new "Mr. President."

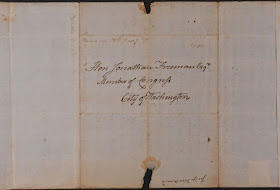

During the interim between the general election and the deciding vote by the House, Hanover community leaders Bezaleel Woodward (Dartmouth College Treasurer) and John Wheelock (Dartmouth College President) further sported the Federalist spirit of New England in letters to their New Hampshire Congressman, Jonathan Freeman; however, they also appealed to their representative to support Jefferson. On January 23, 1801 Woodward wrote to Freeman calling the defeat of Adams "mortifying," yet he also proposed that "we may perhaps have some reason to hope what has been said & written will induce Mr. Jefferson to consult the true interests of the U.S." Similarly on February 14, 1801 Wheelock described how "The good old friends to the government in this quarter, and you know their number is great & precious, retain their firmness for the constitution & order," echoing, although in a more mild manner, Burleigh's description of a state under Federalist control. However, unlike Burleigh, Wheelock did not believe a Jeffersonian administration would declare war on the Constitution. Instead he calls the document "an anchor ground for the ship of storm," believing that the Constitution would maintain the principles of the Republic. He endorsed Jefferson, claiming that "whatever his religious principles may be, he will have the strongest motives of interest, and honor, & true policy, to be attached to the constitution & the general good, and to avoid the insulation of party."

Their voices were heard, and the House bestowed the title of President of the United States upon the supposed atheist and Constitution-hater, Mr. Jefferson. Timing, timing, timing. Oh how the Federalists' opinion, right in Hanover, changed with the circumstances. Although it is unclear how Wheelock and Woodward viewed Jefferson prior to Adams's defeat or how Burleigh or Davis's general readers saw him after, beyond displaying the regional political affiliations, their words reveal the power of the tediously printed press and elegantly styled ink for politics in the early Republic.

To see the newspaper article or letters, ask for:

Dartmouth Gazette (LH1.D3 D255, V1), Mss 801164 Wheelock to Freeman and Mss 801123.1 B. Woodward to Freeman.

Posted for Haley Shaw '15

No comments:

Post a Comment