Shipwrecks capture the imagination with epic tales of tragedy and heroism. From

Robinson Crusoe to

Life of Pi, shipwrecks have provided readers stories of life and death they just can’t put down. While Rauner has endless books on shipwrecks, it also has its own relics of a voyage gone wrong. Over the years, a number of tokens from the last voyage of the HMCS

Karluk have washed up on Rauner's shelves.

Viljhalmur Stefansson, who taught at Dartmouth from 1947 to 1962, organized the

Karluk's voyage to explore the area north of the Canadian coast.

Karluk began its journey in June 1913. The Executive Council of British Columbia presented Stefansson with a silver salver upon his departure. However, the crew would soon need more practical goods than an engraved tray. By September 10th,

Karluk was ice-bound for the winter. Stefansson became separated from the ship: Karluk began to drift through the ice while he was on a hunting trip with five other members of the expedition. Though Stefansson claimed the separation was accidental, some of the remaining crew saw his departure as the abandonment of a mission he suspected would fail. Stefansson did not return from the trip until 1918 after an extensive exploration that included the discovery of new Islands, but the

Karluk sunk after months of drifting on January 10th, 1914.

The sinking of

Karluk left twenty-two men, one woman and two children stranded on what would become known as "Shipwreck Camp." Divisions between the shipwrecked soon arose on the ice camp. Two parties set out in attempt to reach Wrangel Island and set up a more permanent site on land. These parties overestimated how close they were to the island and the ease with which they could set up a new camp. Both perished in the Arctic conditions. Finally, the main party managed to reach Wrangel Island in March. The captain, Robert Bartlett, and an Inuit hunter, Kataktovic, continued on in search of a means to alert the rest of the world of the fate of

Karluk. The rest of the group set up camp, desperately awaiting rescue. Finally, on September 7th, a walrus hunting ship accompanied by Bartlett picked up the fourteen remaining survivors.

Six survivors would publish first-hand accounts of "the last voyage of the

Karluk." Bartlett went on to lead many more Arctic voyages. Stefansson lectured widely on "the Friendly Arctic," organized another ill-fated expedition to Wrangel Island and eventually became the Director of Polar Studies at Dartmouth. You can find much more about the

Karluk and practically anything else related to the polar regions by exploring the

Stefansson Collection on Polar Exploration.

Posted for Kate Taylor '13

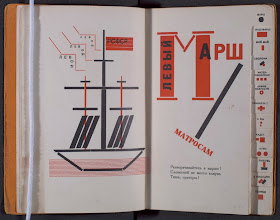

Vladamir Maiakovsky's poems were meant to be read aloud; in fact, the title of this book, Dlia Golosa (Berlin : R.S.F.S.R. gosudarstvennoe izdatelʹstvo, 1923) translates to For the Voice. El Lissitzky applied his Constructivist aesthetic to the book. Drawing

primarily on display types and decorative devices common in printing

shops he illustrated the poems and created emphasis. You have to wonder, if the book is meant to be heard rather read, why the lavish typographic attention?

Vladamir Maiakovsky's poems were meant to be read aloud; in fact, the title of this book, Dlia Golosa (Berlin : R.S.F.S.R. gosudarstvennoe izdatelʹstvo, 1923) translates to For the Voice. El Lissitzky applied his Constructivist aesthetic to the book. Drawing

primarily on display types and decorative devices common in printing

shops he illustrated the poems and created emphasis. You have to wonder, if the book is meant to be heard rather read, why the lavish typographic attention?