In the early 20th century, eugenics—or the study of optimizing reproduction to promote “favorable traits” in a human population—took root throughout the United States. The scope of projects relating to the promotion of eugenical philosophies—ranging from forced sterilization to encouraging reproduction between “more fit” individuals—influenced policies and projects at governmental, social, and scientific levels. While most principles regarding eugenics have now been proven false and based in discriminatory principles, they were an active area of study and concern for many decades. Consequently, the public interest in the discipline during this time created several unique programs centered at better understanding familial genetics and heritability.

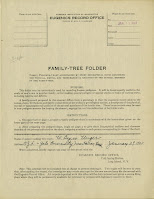

In the early 20th century, eugenics—or the study of optimizing reproduction to promote “favorable traits” in a human population—took root throughout the United States. The scope of projects relating to the promotion of eugenical philosophies—ranging from forced sterilization to encouraging reproduction between “more fit” individuals—influenced policies and projects at governmental, social, and scientific levels. While most principles regarding eugenics have now been proven false and based in discriminatory principles, they were an active area of study and concern for many decades. Consequently, the public interest in the discipline during this time created several unique programs centered at better understanding familial genetics and heritability.One of these projects, created by the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Eugenics Record Office (ERO), was the “Family-Tree Folder”. The ERO branded itself as “a repository of eugenic data, with an ‘analytical index’ to allow the study of the hereditary transmission of the ‘inborn traits’ of American families.” (EugenicsArchive) The organization built this archive, containing massive amounts of data, through the general public’s completion of voluntary surveys. Questionnaires were mailed to interested parties, who input detailed demographic information about their family members and then sent their data to the Eugenics Records Office for indexing and storage. This personal data was then used for eugenical research projects until the closure of the ERO in 1939.

A Dartmouth professor, William B. Unger, took interest in the study of genetics and heredity. As an employee of the College for 40 years, from 1925-1965, he taught coursework in zoology. His archives housed in the Rauner Library, however, demonstrate a close personal interest in genetics not reflected in his academic research or teaching. A search revealed a copy of the “Family-Tree Folder” he had completed for his own relatives.

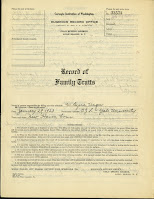

This booklet, sent to him on January 12, 1923, consisted of several components. The first was a pedigree chart aimed at tracking marriages, births, and deaths. Beyond explicit familial relationships, the chart also recommended tracking some of the “hundreds of mental, physical, and moral traits which characterize different families”—including traits like “‘leadership’, ‘talent in vocal music’, or ‘alcoholism.’” This pedigree chart was accompanied by an individual analysis card, where each family member was tracked over 62 characteristics. These included genetically-related traits, such as chronic diseases or hair color, and more subjective traits. Examples included “strength, quality, or register in singing,” any talent in “craftsmanship, carpentry, masonry, or stone cutting”, or “nervous peculiarities - excitability; fretfulness; cruelty conceit; self-depreciation; holds a grudge.”

Close analysis of materials like this reflects the nature of the evidence used to support the claims of the eugenics movement. While some elements of the field eventually translated into legitimate practices—such as genetic counseling, a term coined by Dartmouth alumnus Sheldon Reed '28, referring to risk assessment for genetic and inherited conditions like cystic fibrosis—many data points were collected using practices not scientifically backed, on traits subjectively assessed with little genetic correlation. The ERO, however, largely relied on this mode of data collection to fill their archives. Other materials in the papers of William Unger—including a separate survey titled “Record of Family Traits”—utilized identical practices to collect evidence.

The eugenical ideas of the early 20th century have largely been disproven, as their foundations often lie on scientific racism and pseudoscientific methods. Closer analyses of “scientific tools,” such as Unger’s Family-Tree Folder, reveal why the data used to prove once certain conclusions has crumbled under increasing scrutiny. Nonetheless, projects like these informed policies that were used to discriminate against and often physically harm communities of marginalized identities nationally for decades. In hindsight, history serves as a reminder of the perils that arise when bigotry masquerades as science.

To review William B. Unger's eugenical data, come to Rauner and ask to see MS-833, Box 3, Folder 102.

Posted for Manu Onteeru '24, recipient of a Historical Accountability Student Research Fellowship for the 2024 Spring term. The Historical Accountability Student Research Program provides funding for Dartmouth students to conduct research with primary sources on a topic related to issues of inclusivity and diversity in the college's past. For more information, visit the program's website.