Recent happenings in the news made us remember an odd little relic in the collections: a ticket to Andrew Johnson's impeachment hearing in the U.S. Senate on April 29th, 1868. The blue printed ticket seems like it may not have been used; the stub is detached, but still present. We are not sure if the owner of ticket 729 bothered to show up or if the bearer managed to keep both portions of the ticket.

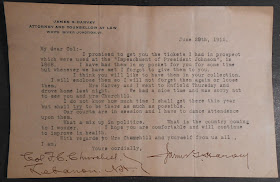

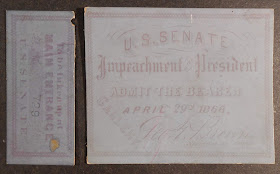

Recent happenings in the news made us remember an odd little relic in the collections: a ticket to Andrew Johnson's impeachment hearing in the U.S. Senate on April 29th, 1868. The blue printed ticket seems like it may not have been used; the stub is detached, but still present. We are not sure if the owner of ticket 729 bothered to show up or if the bearer managed to keep both portions of the ticket.It is accompanied by a letter from James G. Harvey, an attorney in White River Junction, to Colonel F. C. Churchill of Lebanon dated June 29, 1912. The letter starts out simply enough with Harvey telling the Colonel that he is happy to give him the ticket for his collection--he says he has been carrying it around in his pocket but keeps forgetting about it when he sees him. Then, after some niceties, Harvey exclaims: "What a mix up in politics. What is the country coming to I wonder."

Well, that sent us back into the news from that era to see how politics could ever be mixed up and just what was imperiling the country. The front page of the seemingly flourishing New York Times for June 29, 1912, tells the story. The Democratic convention was in its 10th ballot and still no nominee had been chosen. The convention was in Baltimore in the summer and it was blisteringly hot. Eventually Woodrow Wilson won the nomination on, get this, the 46th ballot! Wilson went on to win the Presidency later that year.

If you are interested in seeing the Johnson impeachment ticket and accompanying letter, ask for MS868279