There has been a great deal of excitement on campus around the Library’s acquisition of the Mario Puzo Papers. Of course, Puzo is most well-known for writing the novel The Godfather and its subsequent screenplays, but his papers also reveal that he was a prodigious writer who worked across a range of literary forms. Alongside The Godfather material, drafts of scripts for superhero and disaster movies, a young adult novella, pithy works of cultural criticism, and memoiristic essays are also present in the collection. Puzo’s Inside Las Vegas (1977)—a sort of love letter from the author to the City of Sin (he was a self-described “degenerate gambler”)—appears to be a particularly unique publication in Puzo’s oeuvre. This is due to its inclusion of a corresponding photo essay that documents, in both black and white and color, the spectacle of life on the Vegas Strip.

There has been a great deal of excitement on campus around the Library’s acquisition of the Mario Puzo Papers. Of course, Puzo is most well-known for writing the novel The Godfather and its subsequent screenplays, but his papers also reveal that he was a prodigious writer who worked across a range of literary forms. Alongside The Godfather material, drafts of scripts for superhero and disaster movies, a young adult novella, pithy works of cultural criticism, and memoiristic essays are also present in the collection. Puzo’s Inside Las Vegas (1977)—a sort of love letter from the author to the City of Sin (he was a self-described “degenerate gambler”)—appears to be a particularly unique publication in Puzo’s oeuvre. This is due to its inclusion of a corresponding photo essay that documents, in both black and white and color, the spectacle of life on the Vegas Strip. The striking photographs in Inside Las Vegas are both journalistic and artistic in nature. Black and white portraits of working show girls and newlyweds are depicted in a documentary style with compositional precision. Cityscapes, printed in color, are littered with bright lights and at times border on abstraction. Original prints of many of the book’s images (as well as others that were not selected for publication) can be found in Puzo’s papers.

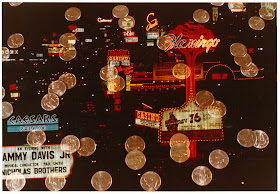

The striking photographs in Inside Las Vegas are both journalistic and artistic in nature. Black and white portraits of working show girls and newlyweds are depicted in a documentary style with compositional precision. Cityscapes, printed in color, are littered with bright lights and at times border on abstraction. Original prints of many of the book’s images (as well as others that were not selected for publication) can be found in Puzo’s papers.While Inside Las Vegas as a whole offers revealing insights into Puzo’s vision of Las Vegas, taken separately, the photographs themselves have broader relevance to important currents in the history of photo journalism. John Launois, Michael Abramson, and Susan Fowler-Gallagher, the photographers responsible for the images in the book, were represented by Howard Chapnick at the famous New York City Black Star photo agency. Black Star was founded in 1935 in New York City by Earnest Mayer, Kurt Safrasnki and Kurt Kornfeld, Jewish emigres who had fled Nazi Germany and brought with them their knowledge of the increasingly popular format of photojournalism and the extended photo essay. Safranski, in particular, had previously worked at Berliner Ilustrite Zeitung (BIZ), the weekly German publication that is often considered the pioneer of photojournalism.

Black Star quickly became the gold standard in commercial photography throughout a substantial portion of the twentieth century. Life magazine, founded just a year after Black Star in 1936, was one of the agency’s earliest and most important clients, and other notable clients would include The Saturday Evening Post, The New York Times, Time and Newsweek. In major outlets such as these, Black Star photographers helped to bring some of the most iconic images of the mid-twentieth century to the broader American public. They were responsible for documenting the historic events that have come to define the era: the assassination of JFK, the march on Selma, the fall of the Berlin Wall, just to name a few. Even Andy Warhol, who often repurposed journalistic images and symbols of pop-culture, used an image from a Black Star photographer in his Race Riot (1964) (it reproduced Charles Moore’s Life magazine photographs of black protestors being attacked by police dogs in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963).

Black Star quickly became the gold standard in commercial photography throughout a substantial portion of the twentieth century. Life magazine, founded just a year after Black Star in 1936, was one of the agency’s earliest and most important clients, and other notable clients would include The Saturday Evening Post, The New York Times, Time and Newsweek. In major outlets such as these, Black Star photographers helped to bring some of the most iconic images of the mid-twentieth century to the broader American public. They were responsible for documenting the historic events that have come to define the era: the assassination of JFK, the march on Selma, the fall of the Berlin Wall, just to name a few. Even Andy Warhol, who often repurposed journalistic images and symbols of pop-culture, used an image from a Black Star photographer in his Race Riot (1964) (it reproduced Charles Moore’s Life magazine photographs of black protestors being attacked by police dogs in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963).John Launois, one of the photographers who worked on Puzo’s Inside Las Vegas book, also documented Malcolm X's pilgrimage to Egypt, and shot the recognizable images of a young Bob Dylan on his motorcycle which appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1964. Michael Abramson, also a contributor to Inside Las Vegas, was a Chicago-based photographer who documented the black night club scene in the '70s and '80s to critical acclaim. His work is now found in the permanent collections at the Smithsonian and the Chicago Art Institute, among others.

While the Mario Puzo papers provide researchers a valuable new archive for examining “obvious” topics, such as literary depictions of Italian Americans, it may also open doors to more unexpected finds. A brief investigation into the esteemed Black Star photographers who collaborated on Mario Puzo’s Inside Las Vegas suggests something of the high status that Puzo had achieved in the publishing world by 1977—eight years after the publication of The Godfather, and five years after Godfather II won a best picture Oscar. But this collection may also offer unexpected riches for scholars and researchers such as those interested in this important group of midcentury photojournalists.

You can ask for MS-1371 to see more. As soon as the finding aid is ready, we will post a link here (Update: here it is).