“This is the very first I ever had published …” reads Robert Frost’s words penned atop this newspaper. On November 8, 1894,

The Independent, a New York newspaper which ran from 1848-1921, became the first professional publisher to feature poetry by Robert L. Frost.

However,

The Independent was not the first to

print Frost’s poetry, or even “My Butterfly.” Frost worked with a

printer in Lawrence, Massachusetts to self-publish two copies of a

collection he called

Twilight, one for himself and one gifted to his future wife, Elinor. Only Elinor’s copy of

Twilight

survives today – after personally delivering

Elinor’s copy to her at St. Lawrence College and perceiving rejection, Frost destroyed his copy.

While Elinor's copy of

Twilight is housed in special collections

at the University of Virginia, Dartmouth’s Rauner Alumni

Collection features an original copy of the

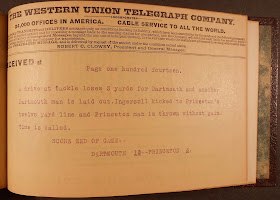

Independent, issue number 2397.

This particular copy features a brief note penned by Frost dedicated to

one Earle Bernheimer. Bernheimer, it turns out, was a patron of Frost

who supported him financially in exchange for bits of writing from the

poet. Their letters suggest that, at least for Frost, the relationship

was more business than friendship, and that he got Bernheimer to

progressively pay him more and more for less and less. Ultimately,

Bernheimer had to sell his collection of Frost’s works during a divorce

settlement. It is quite possible that this piece was part of that very

collection.

The poem, “My Butterfly” itself was written by Frost at

eighteen and was also featured in his first commercially published book

of poems

A Boy’s Will. Another thing that stands out about the

poem is its use of poeticisms – formalistic flairs like thee, tis, and

o’er – which slowly fled Frost’s work as he progressed as a poet. On

January 30, 1895 Frost composed a letter concerning “My Butterfly” to

Susan Hayes Ward, an editor for

The Independent, “If it is seriously I must speak, I undertake a future. I cannot believe that poem was merely a chance. I will surpass it.”

The rest of Frost's inscription quoted above is "...unless you count the three or four I had in the Lawrence High School Bulletin when I was at school." We have one of those, too. To see "My Butterfly" ask for

Alumni F9296my; to see the Bulletin, ask for

Frost LH1 L285 H54 1892.

Posted for Bradford Stone '19.

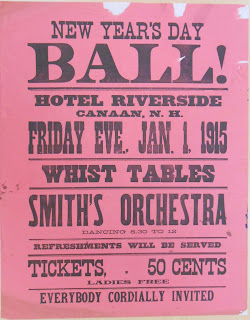

Folks in Canaan, New Hampshire, were living it up at the start of 1915. It is a contrast to the somber mood of war torn Europe that we just blogged about. Apparently, the revelry of New Year's Eve wasn't enough, so the Hotel Riverside had a plan: a New Year's Day Ball with Smith's Orchestra and refreshments. Tickets for the gentlemen were 50 cents, but the "ladies" got in for free.

Folks in Canaan, New Hampshire, were living it up at the start of 1915. It is a contrast to the somber mood of war torn Europe that we just blogged about. Apparently, the revelry of New Year's Eve wasn't enough, so the Hotel Riverside had a plan: a New Year's Day Ball with Smith's Orchestra and refreshments. Tickets for the gentlemen were 50 cents, but the "ladies" got in for free.