If you live in the Americas, there is a good chance that your country celebrated Columbus Day this past Monday. In the United States, the holidays of both Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples' Day now uneasily occupy the same date on our calendar here in the United States. In some regions of the country, Columbus is seen in such a negative light that his holiday is not recognized at all. In particular, Alaska, Hawaii, Oregon, and South Dakota, do not formally celebrate Columbus Day.

The controversy over Columbus that has raged on social media this week, combined with a Writing 5 class on Monday that explored world-building through word and image, has us thinking about the early days of exploration by the Spanish government on this continent. One of the books that we used in the class was a 1598 edition of Bartolome De Las Casas's A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. De Las Casas was one of the first Spanish colonists to arrive in the new world; he immigrated with his father to Hispaniola with he was about eighteen years old. De Las Casas was originally a slave owner who controlled an estate that garnered him profits via the encomienda labor system, which gave the beneficiary the legal right to own a number of indigenous

people in exchange for protecting Spanish interests in the region. He and his family knew the Columbuses because they had sailed with them to the Americas; Diego Columbus, Christopher's eldest son, was the Governor of the Indies during De Las Casas's time in Hispaniola.

However, in his early thirties, De Las Casas had a change of heart; he had witnessed the atrocities visited upon the indigenous community by their Spanish overlords, and was deeply troubled by the abuse and exploitation he witnessed. In 1515, he gave up his slaves and his resulting profits from their labor and instead began to advocate on behalf of the indigenous population in the Spanish Americas. He eventually entered the Dominican order and became a zealous proponent for ending the physical abuse and cruel treatment of native peoples. Ultimately, De Las Casas would be appointed to the administrative office of Protector of the Indians and serve as a liaison, advisor, and advocate for indigenous peoples and the rulers of the Spanish colonies. De Las Casas was by no means a singularly heroic figure; he had many flaws, including a belief in slavery as an acceptable practice that stayed with him for many years. Still, he made some small advances in a more humane official approach to treatment of colonized people by the Spanish government.

A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies was one of De Las Casas's most powerful writings, sent to King Philip II of Spain after its publication in 1552. De Las Casas intended the book to be a wake-up call to the Spanish people because he feared for the state of their souls if they continued their abusive and exploitative treatment of other cultures. The already controversial text was later independently illustrated by a Dutch Protestant, Theodor de Bry, whose graphic depictions of horrific violence enacted by the Spanish soldiers shifted the emphasis of the text from jeremiad to anti-Spanish propaganda.

To see more of de Bry's engravings, or to engage with De Las Casas's argument in Latin, come to Rauner and ask to see McGregor 33.

Friday, October 13, 2017

Tuesday, October 10, 2017

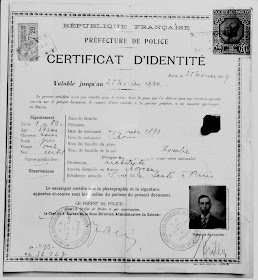

The "Nansen passport"

|

| "Nansen passport." From United Nations High Commission for Refugees, Nansen Centennial, 1961. |

Nansen earned early fame as the leader of the first team to cross the interior of Greenland - he skied across in 1888 - and for his attempt to reach the North Pole. Though he didn't quite make it to the Pole, he came within a few degrees - again skiing the final leg of the journey. We've blogged about the ads that filled out his serialized Farthest North.

During his work for the League of Nations, Nansen was deeply involved in resettling Russian refugees following the Revolution. One of the innovations he introduced was the "Nansen passport," an identity document accepted by numerous governments which granted displaced and stateless people the ability to travel across international borders. For this and other efforts he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

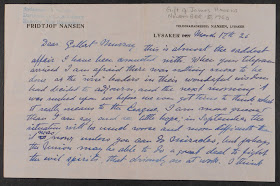

Though most of Rauner's Nansen material focuses on his polar explorations, we do hold a few items related to his humanitarian work, including a letter to Gilbert Murray from 1926 in which he discusses "the saddest affair I have ever been connected with." Though Nansen doesn't specify the subject, he may be alluding to his work resettling Armenians following the attempted genocide by the Ottoman Empire.

A guide is available for Stef Mss-156.