Historians agree that Eleazar Wheelock met his end on April 24, 1779, but that’s about where agreement ends. Some record his age as 68 and others as 69. Most simply skip over the details and only report the date.

Historians agree that Eleazar Wheelock met his end on April 24, 1779, but that’s about where agreement ends. Some record his age as 68 and others as 69. Most simply skip over the details and only report the date.David McClure, the most contemporary of the writers, in his 1811 Memoirs of the Rev. Eleazar Wheelcok, D.D. Founder and President of Dartmouth College, is the only historian to provide any detail. He notes that at the beginning of April 1779, Wheelock’s health went into rapid decline. From there McClure paints an almost perfect bedside death where Wheelock, surrounded by family, declares that he does not fear death, repeats the 23rd Psalm, and expresses a desire to “depart and to be with Christ.” He records Wheelock’s last words, as “Oh my family be faithful unto death.” He then notes that Wheelock “expired without a struggle or a groan. The peace and joy of his mind, in the moment of death, impressed a pleasing smile on his countenance.”

This is how death was supposed to play out in the 18th century, particularly for a devout man of the cloth like Wheelock. But is this really how he died? Until earlier this year, we had no reason to think otherwise, but recently a staff member discovered an alternative account while researching deaths in Hanover. This alternative account was recorded by William Worthington Dewey. According to Chase’s History of Hanover and Dartmouth College, Dewey arrived in the area at the age of two years in 1779 when his father, Benoni Dewey, came here to run the blacksmith shop. William W. Dewey appears to have run a temperance house for a period of time, built several local houses and may have been a farmer. In addition to these varied trades, he also had a strong interest in local history that tended toward the macabre. During his lifetime, he compiled a set of notes of deaths in Hanover and the surrounding area. One of the first death’s he discusses is that of Eleazar Wheelock. Dewey’s description of Wheelock’s last moments was clearly gleaned from his father. Here is his father’s account:

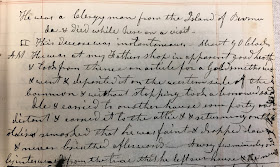

This is how death was supposed to play out in the 18th century, particularly for a devout man of the cloth like Wheelock. But is this really how he died? Until earlier this year, we had no reason to think otherwise, but recently a staff member discovered an alternative account while researching deaths in Hanover. This alternative account was recorded by William Worthington Dewey. According to Chase’s History of Hanover and Dartmouth College, Dewey arrived in the area at the age of two years in 1779 when his father, Benoni Dewey, came here to run the blacksmith shop. William W. Dewey appears to have run a temperance house for a period of time, built several local houses and may have been a farmer. In addition to these varied trades, he also had a strong interest in local history that tended toward the macabre. During his lifetime, he compiled a set of notes of deaths in Hanover and the surrounding area. One of the first death’s he discusses is that of Eleazar Wheelock. Dewey’s description of Wheelock’s last moments was clearly gleaned from his father. Here is his father’s account:His decease was instantaneous. About 9 O Clock AM He was at my Fathers shop in apparent good health & took from thence an article for a Goldsmiths use & went & deposited it on the western side of the common & without stopping took a borrowed saddle & carried to another house some forty rod distant & carried it to the attic && returning on the stairs remarked that he was faint & dropped down & never breathed afterwards – A very few minutes only intervened from the time he that left our house & the news of His decease.This rendition of Wheelock’s final moment stands in stark contrast to that given by McClure, but has, in its simplicity, the ring of truth. Unfortunately, until we discover another account that conflicts with or verifies one or the other of these versions, we will never be able to determine what actually transpired.

To read William Worthington Dewey’s account of Wheelock’s demise, or to just read his interesting account detailing the deaths of Hanover residents between 1769 and 1859, come to Rauner and ask to see MS-1264, Box 1, Folder 2: "List of deaths in the vicinity of Dartmouth College, including likewise the hamlet usually called Greensborough from AD 1769 to 1859"