In 1967, here in Webster Hall, a group of Dartmouth students stood up during a speech by Alabama's segregationist governor, George Wallace, and vocally protested. They disrupted the speech and turned the campus on its head. A raging debate ensued over the nature of civil discourse and protest on a college campus. Emotions ran high, and the campus was polarized. It sounds kind of familiar....

In 1967, here in Webster Hall, a group of Dartmouth students stood up during a speech by Alabama's segregationist governor, George Wallace, and vocally protested. They disrupted the speech and turned the campus on its head. A raging debate ensued over the nature of civil discourse and protest on a college campus. Emotions ran high, and the campus was polarized. It sounds kind of familiar.... Last week we found two student-run magazines that give us a look into the debate. The Conservative Idea, which had been around for about a year, devoted it's May 1967 issue to the controversy. The cover dismissed the validity of the protests by quoting Napoleon: "Vanity made the revolution; liberty was only a pretext."

Last week we found two student-run magazines that give us a look into the debate. The Conservative Idea, which had been around for about a year, devoted it's May 1967 issue to the controversy. The cover dismissed the validity of the protests by quoting Napoleon: "Vanity made the revolution; liberty was only a pretext."

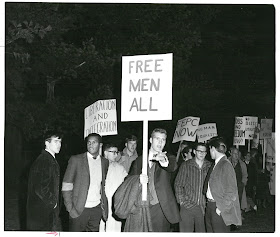

The newly created Blackout, published by the Dartmouth Afro-American Society, countered with their Fall term, 1967 issue. The cover sports the members of the Afro-American Society holding signs spelling out "BLACK POWER NOW." Presumably, these are some of the same students who shouted down Wallace and are pictured on the Conservative Idea cover. The issue is devoted to discussions of civil rights and protest--it leads not with a quote by Napoleon, but by Thoreau: "A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight."

To see how the debate played out in these two partisan magazines ask for DC History LH1 .B55 for Blackout, and DC History LH1 .D3C6 for the Conservative Idea. They are practically right next to each other on the shelf. Have they found peace by being so close together for the past 50 years?