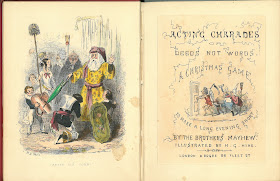

Try Acting Charades! This 19th century pastime is way more complicated than what we call charades today. There's a whole book dedicated to the proper art of Acting Charades, or, Deeds not Words: A Christmas Game.

Try Acting Charades! This 19th century pastime is way more complicated than what we call charades today. There's a whole book dedicated to the proper art of Acting Charades, or, Deeds not Words: A Christmas Game.The book begins with an introduction to the history of charades (French), so started because of the national "inability to sit still for more than half and hour." As to the actual game, the two "most celebrated performers" choose their teams, then decide upon a two syllable word or phrase. One team then performs a charade -- silently, as "nothing more than an exclamation is allowed" -- "as puzzlingly as possible" in the order of "my first, my second, and my whole." It's somewhat similar to how nowadays, we do "1st syllable" and so on. But these pantomimes are not simple.

Let's follow "Mistletoe."

Act I. Mistle -- (Mizzle). A Poor Tenant cannot pay his rent; he and his family remove all of their belongings from the home. The Angry Landlord arrives and is angry.

Act I. Mistle -- (Mizzle). A Poor Tenant cannot pay his rent; he and his family remove all of their belongings from the home. The Angry Landlord arrives and is angry.Act II. Toe. An English gentleman refuses to kiss the Pope's toe. An Irish gentleman attempts to help, but when the English gentleman is escorted away at broom-point, he joins the Catholic cheers.

Act III. Mistletoe. A grandfather sets up some mistletoe over the Christmas dinner table. Everyone is delighted at this"wickedness," and many couples embrace theatrically ("by crossing their heads over their shoulders") under the mistletoe. Then they have to get married.

Not sure I'd be able to guess "mistletoe" from that, but that's just my 21st century attention-span speaking. Maybe if I were a Victorian scholar ...

My favorite part is the incredible set-up to the actual action itself. It's not like our version of charades -- this requires costumes. And though they understand their are constraints, they expect "high-pressure ingenuity" to save the day. They have seen a Louis XVI with an "ermine victorine wig for a well powdered peruke, and the dressing-gown for embroidered coat." Let me just go get my ermine victorine wig.

To try a charade of your own, ask for Sine Illus H56act. The British Museum also has provided a scanned version via Google Books if you want to try during the winter holiday.