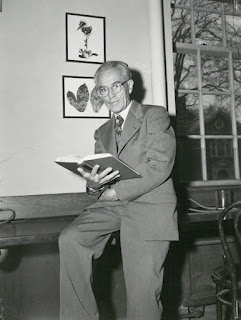

While a freshman at Dartmouth College in 1898, Arthur H. Chivers fell in love with the Old Dartmouth Cemetery. He could often be seen wandering the grounds. After he graduated in 1902, Chivers went on to earn a M.A. and a Ph.D in botany from Harvard. He joined the Dartmouth faculty as an instructor in botany in 1906. He retired a full professor in 1950. During his time at Dartmouth, Chivers was involved with many town and civic affairs. Having never forgotten his love for the cemetery he was happy to take over the supervision of the cemeteries as a member of the Board of Selectman of Hanover in 1948. First on his list of actions regarding the cemeteries in Hanover was to create a card index of all known burials, reading and recording the inscriptions on each stone. By 1951, he had made 1,814 entries.

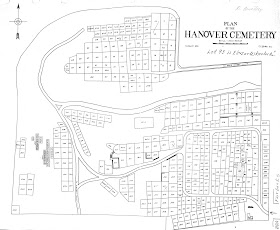

While a freshman at Dartmouth College in 1898, Arthur H. Chivers fell in love with the Old Dartmouth Cemetery. He could often be seen wandering the grounds. After he graduated in 1902, Chivers went on to earn a M.A. and a Ph.D in botany from Harvard. He joined the Dartmouth faculty as an instructor in botany in 1906. He retired a full professor in 1950. During his time at Dartmouth, Chivers was involved with many town and civic affairs. Having never forgotten his love for the cemetery he was happy to take over the supervision of the cemeteries as a member of the Board of Selectman of Hanover in 1948. First on his list of actions regarding the cemeteries in Hanover was to create a card index of all known burials, reading and recording the inscriptions on each stone. By 1951, he had made 1,814 entries. Using William Worthington Dewey's journal "List of Deaths in the Vicinity of Dartmouth College Including Likewise the Hamlet usually Called Greensborough from AD 1769 to 1859," John Richard's "Record of Death, Internments and Descriptions 1771-1858" and official town records, Chivers then proceeded to map out the Old Dartmouth Cemetery, creating a location map and diagrams of every monument, stone and marker. Chivers also discovered that there were many discrepancies between the different sources and so, whenever it was possible, he contacted family members of the deceased to verify dates and names.

Using William Worthington Dewey's journal "List of Deaths in the Vicinity of Dartmouth College Including Likewise the Hamlet usually Called Greensborough from AD 1769 to 1859," John Richard's "Record of Death, Internments and Descriptions 1771-1858" and official town records, Chivers then proceeded to map out the Old Dartmouth Cemetery, creating a location map and diagrams of every monument, stone and marker. Chivers also discovered that there were many discrepancies between the different sources and so, whenever it was possible, he contacted family members of the deceased to verify dates and names.The entire project, a labor of love, took him four years to complete. As part of the process, Chivers could be seen crawling around the cemetery. At one point an unsuspecting visitor to the cemetery was so perturbed by this strange behavior that she rushed away to report it. According to Chivers, she said, "There's a very queer man in the cemetery and I think that the police should be told about him."

In 1952, Chivers gave his research to Kenneth C. Cramer, the college archivist, and it became part of Rauner's cemetery collection DH-38. We recently scanned Chivers's seven three-ring binders and they are available as one searchable record in pdf form on our web page. Since Chivers completed his record more than sixty years ago, many more inscriptions have disappeared. As such his contribution to the history of the Old Dartmouth Cemetery is invaluable. Arthur H. Chivers died in 1981, at the age of 101. At the time of his death, he was the oldest living alum and the only surviving member of the Class of 1902. He is buried in the cemetery that he loved.

Usually we tell you come in and take a look, but this time why not use Chivers's guide as you stroll through the cemetery.