"Dr. Einstein, why is it that when the mind of man has stretched so far as to discover the structure of the atom we have been unable to devise the political means to keep the atom from destroying us?" "That is simple, my friend. It is because politics is more difficult than physics."

"Dr. Einstein, why is it that when the mind of man has stretched so far as to discover the structure of the atom we have been unable to devise the political means to keep the atom from destroying us?" "That is simple, my friend. It is because politics is more difficult than physics."

Grenville Clark quoted this memorable exchange in a tribute he wrote for Einstein published in the New York Times following Einstein's death in April 1955. Clark had overheard this conversation at a conference about disarmament and world government that took place in January 1946, at Princeton, New Jersey, five months after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Clark was a prominent Harvard educated New England lawyer who was deeply involved in the world government movement. This political movement advocated two imperatives following World War II: no peace without disarmament and no disarmament without limited world government. The Princeton Conference, which Albert Einstein attended, was a continuation of a prior conference that took place in Dublin, New Hampshire, in October 1945. Clark organized this series of conferences as a way to forward proposals for a world government and amend the United Nations Charter. Clark and the conference attendees, including Albert Einstein, sought to make the United Nations a truly effective world institution for the maintenance of peace in a disarmed world governed by law.

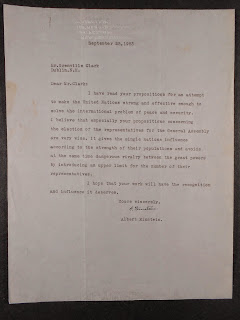

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Clark worked tirelessly as a leading advocate for the world government movement. In 1953, Clark published a book titled, Peace Through Disarmament and Charter Revision: Detailed Proposals for Revision of the United Nations Charter, which Albert Einstein read and commented on in a letter he sent to Clark in September of that year. In this letter, Einstein stated how he had "read [Clark's] propositions for an attempt to make the United Nations strong and effective enough to solve the international problem of peace and security" and "hope[d] that [his] work will have the recognition and influence it deserves."

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Clark worked tirelessly as a leading advocate for the world government movement. In 1953, Clark published a book titled, Peace Through Disarmament and Charter Revision: Detailed Proposals for Revision of the United Nations Charter, which Albert Einstein read and commented on in a letter he sent to Clark in September of that year. In this letter, Einstein stated how he had "read [Clark's] propositions for an attempt to make the United Nations strong and effective enough to solve the international problem of peace and security" and "hope[d] that [his] work will have the recognition and influence it deserves."

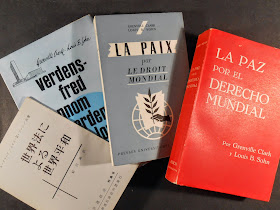

Clark's dedication to achieving world peace through enforceable world law became the subject of his major work, World Peace Through World Law, co-authored with Louis B. Sohn. In this book, Clark and Sohn proposed revisions to the United Nations Charter. This book advocated for a truly international world state, a unicameral parliament chosen on the basis of weighted population bases, a vetoless executive arm, a world court, and a world police force. Following its publication in 1958, World Peace Through World Law was translated into numerous languages and became a classic of international relations.

To see Einstein's correspondence with Clark, come to Rauner and ask for ML-7 box 160, folder 70. To see the numerous translations of World Peace Through World Law, ask for Rare JX 1977 .C554. And lastly, if you’re interested in learning more about Grenville Clark in general, check out the full finding aid to his papers at Dartmouth.