The adage that “all your dysfunctional relationships have one thing in common, you” comes to mind whenever Eleazar Wheelock’s legacy is up for examination. This is particularly the case with a recent acquisition of Wheelock documents (five in his hand) ranging from the time of his calling to the Second Congregational Church in Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1735 to 1771 after his arrival in Hanover.

The adage that “all your dysfunctional relationships have one thing in common, you” comes to mind whenever Eleazar Wheelock’s legacy is up for examination. This is particularly the case with a recent acquisition of Wheelock documents (five in his hand) ranging from the time of his calling to the Second Congregational Church in Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1735 to 1771 after his arrival in Hanover.Most of the documents deal with conflict: a court case, a disagreement between a minister and his congregation or between one minister and another. Others are less controversial and focus on the installment of a minister, or an invitation to Wheelock, a renowned preacher in his time, to give a sermon at another church.

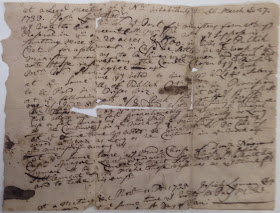

One of the most interesting items in this group of documents is a scrap of well-worn paper in Wheelock’s hand that is coming apart at the creases. Picking through the chicken scratch it becomes evident these are notes that Wheelock took perhaps during the negotiations regarding his ministry in Lebanon, Connecticut. The notes outline what the congregation had agreed to provide Wheelock as compensation for his ministerial efforts, they specifically record that he would be paid £140 per year in public credit or provisions with the types of provisions and amounts carefully noted. The provisions included wheat, corn, oats and pork and beef. The notes also record that Wheelock was to be paid yearly on the first of January. This agreement was drawn up by a savvy group of flinty Connecticut farmers and businessmen who found ways to reinterpret it, or so Wheelock felt, to his disadvantage. It very soon became a source of conflict between Wheelock and the congregation that would plague him until resigned his position.

The crux of the issue appears to have been how these provisions were to be provided based on the rise and fall of their value. The deficit created by the congregation’s interpretation of this agreement was one of the factors that led Wheelock to take on students for tutoring as a way to supplement his income. This in turn led to his tutoring Samson Occom. It was Occom’s success as a scholar that led Wheelock to the idea of educating Native Americans. So, in a sense, this scrap of paper covered in scratchy hand, is the genesis for the eventual founding of Dartmouth College.

To see Wheelock's notes and two later “clean copies” that he made of the specific areas of disagreement, ask for MS-1310, box 1, folders 735227. 1, 735227.2, 735227.3