In 1941, Budd Schulberg '36 published his first novel: What Makes Sammy Run? As a child of the studios (his father had been head of Paramount), and a frustrated screenwriter, he unleashed a torrent of criticism on Hollywood in his novel about the rise of Sammy Glick. The novel became a bestseller in the United States and has often been pointed to as the great American novel about Hollywood.

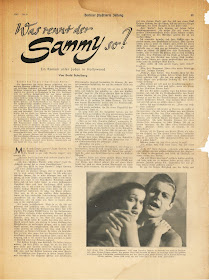

In 1941, Budd Schulberg '36 published his first novel: What Makes Sammy Run? As a child of the studios (his father had been head of Paramount), and a frustrated screenwriter, he unleashed a torrent of criticism on Hollywood in his novel about the rise of Sammy Glick. The novel became a bestseller in the United States and has often been pointed to as the great American novel about Hollywood.Schulberg knew he was taking a risk when he published the novel. It was destined to offend many of the most powerful people in Hollywood. But he did not anticipate that the novel would become fodder for the Nazi propaganda machine. Sammy Glick, the novel's offensive, back-stabbing anti-hero, was Jewish. The Nazis picked up the story and produced a translation edited to highlight the offenses of Jews in Hollywood and portray Sammy as the quintessential American Jew. Then they published it serially in the popular Berliner Illustriere Zeitung where Schulberg's words were turned against the Jewish people.

Ironically, Budd and his brother Stuart were later employed by the U.S. military to splice together film footage to be used against Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg. Their work was made particularly effective by their juxtaposition of Nazi propaganda with scenes of atrocities. For Schulberg, the appropriation of Nazi propaganda must have been a particularly sweet form of personal revenge.

To see how Sammy looked in 1942 Berlin, ask for MS-978, Box 6, Folder 4. And, as a reminder, our current exhibition, Budd Schulberg and the Scripting of Social Change, runs through January 30, 2015 in the Class of 1965 Galleries. And, for more on Schulberg, see these postings from August 9, 2011 and November 4, 2014.