As part of the on-going student protests that we commented on in our last post, a group of students put up some homemade posters in the 1902 Room in Baker Library last night. These posters were designed to contrast with the predominately white and male deans of the College represented in the portraits in the room (to be fair there are three men of color on those walls also). The students labeled their exhibit "Reframing History."

We thought we would highlight another member of Dartmouth's family who did not appear in the student's posters.

Ernest Everett Just, Class of 1907, came to Dartmouth from Kimball Union Academy, a private boarding school with a long affiliation with the College.

Just received a small scholarship from Dartmouth, but had to work to pay his bills. In the early part of the 20th century Dartmouth was a rough place for students of lesser means, which were all students of color. The College did not have a meal plan and students were required to pay as they went for their food. In addition, dorm rooms were spartan. In fact, the catalog notes that rooms were "furnished with bedsteads, mattresses, chiffonieres (a set of drawers) and chairs if desired." The student handbook goes so far as to warn freshmen (under a section titled "Some Suggestions"): "If you are rooming in a dormitory don't let the former occupant of the room sell you the radiator or the roller curtains, they come with the room."

While some poorer students complained of going all day without eating and using their overcoat for a blanket, we don't know if this was typical, or if Just suffered in the same way, but we do know that he lived in the least expensive dormitory on campus. Hallgarten, nicknamed Hellgate by the students who lived there, was on the edge of campus in an undesirable location close to the heating plant.

As we can see from Just's grade card, he had a rough start at Dartmouth. He managed pretty well his first year, pulling a respectable (and then common) gentleman's C. Then he experienced the classic Sophomore slump - I'm sure many of us have been there - failing a class in the first term and again in the second term.

We know from the rules that Just must have taken makeup exams the summer after his sophomore year and passed them, because he returns the following term. And it would seem with renewed determination, achieving an impressive A average.

It is worth noting that the load and subject matter he was required to cover looks pretty daunting from today's perspective. Freshman in the scientific school were required to have some knowledge of Latin, Greek, French and German by the end of their second year.

By Just's junior year he had found his chosen field. Biology dominated his time. In 1905-06 he took 18 hours of Biology In his senior year, he took Vertebrate Embryology, Systemic Morphology of Plants, Research Work and a Zoological Seminar.

It is likely that Just's interest in Biology came from a course he took in his Sophomore year with William Patten. Patten was an early proponent of the theory of evolution and taught this in his course "Principals of Biology." Patten later took Just on as a sort of research assistant and cited Just's research in his work

The Evolution of the Vertebrates and Their Kin.

While Patten was clearly the person who mentored Just into the field there is evidence that another member of the faculty, John Gerould, also played a role in his development as a scientist.

|

| John Gerould |

Just's relationship with Gerould is particularly interesting because Gerould was a Eugenicist. Eugenics is often referred to as a pseudoscience. Practitioners of what is referred to as negative Eugenics advocated for selective breeding or sterilization to improve the human gene pool. This included limiting or ending reproduction of those seen as burdensome to society or degenerate; the poor, those of so called inferior races, the mentally ill and homosexuals. The most infamous application of negative Eugenics, and one we are all familiar with, occurred in Nazi Germany. But there were projects here in the United States as well, including the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment aimed at black men, and the University of Vermont Eugenics project in the 1920s aimed at Abenaki Indians and French Canadians.

Though Gerould was not a major player in Eugenics, he was a friend of Charles Davenport, a leader in the Eugenics movement and Davenport funded some of Gerould's research. Kenneth Manning, Just's biographer, states that Gerould was always confused over Just's race. Manning reports that Gerould "preferred to see Just as white" crediting him with a white father or grandfather.

Just's relationship with Gerould does not suggest that Just was involved, or even interested in, the Eugenics movement, but it is ironic that a young black man could enter an elite, predominately white, Northern college and end up being mentored by a Eugenicist.

This was not the only irony of Just's Dartmouth. Despite the presence of an unprecedented number of black students on campus at that time (during President Tucker's tenure, 1893-1909, there were 17 black students admitted to Dartmouth), and despite the fact that one of them was a football star, white students did not see a problem with holding Minstrel show fundraisers or devising hazing rituals for freshman featuring white students in blackface.

Despite these conflicting social dynamics, Just managed to navigate what could only have been a strange land for a young man from South Carolina. In 1907, having maintained two terms with an A average, Just graduated Magna Cum Laude in Biology with minors in both Greek and History. In addition, he was twice named a Choate Scholar, an award reserved for those with a grade point average of 92 or better. He also won the Grimes Medal, an honor awarded for general improvement by a student in his senior year.

Just went on from Dartmouth to teach at Howard University and from there to the University of Chicago for graduate work. On completion of his Ph. D., he returned to Howard to teach zoology and physiology, a position he held until his untimely death at the age of 57.

While many of Dartmouth's early black graduates went on to distinguished careers (government officials, lawyers, teachers, doctors, photographers and professors), Just's academic achievements, and later National recognition for his scientific work, make him particularly noteworthy. Following in the footsteps of a long line of other organizations and institutions, Dartmouth itself recognized this in 1981 when it established the Ernest Everett Just '07 Professorship in the Natural Sciences.

Ask for Just's Alumni File (Class of 1907), John Gerould's papers (

MS-1040) and William Patten's papers (

MS-512).

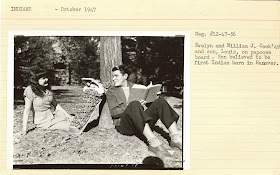

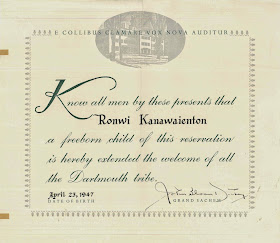

On April 23rd, 1947, Thomas Louis Cook was born in Hanover, NH, to Bill Cook '49 and his wife Evelyn. Bill Cook was a decorated World War II airman who had received numerous commendations for his service to his country, including a Purple Heart for a gunshot wound inflicted during the US Marines' occupation of Peleliu Island in the fall of 1944. After the war, he and his wife came to Dartmouth, where he distinguished himself as a lacrosse player and she ran a small crafts store in downtown Hanover.

On April 23rd, 1947, Thomas Louis Cook was born in Hanover, NH, to Bill Cook '49 and his wife Evelyn. Bill Cook was a decorated World War II airman who had received numerous commendations for his service to his country, including a Purple Heart for a gunshot wound inflicted during the US Marines' occupation of Peleliu Island in the fall of 1944. After the war, he and his wife came to Dartmouth, where he distinguished himself as a lacrosse player and she ran a small crafts store in downtown Hanover. Although the enthusiasm of the College seems genuine enough, its interactions with Ronwi and his parents reveal the struggle of the Dartmouth community to differentiate between its traditional appropriation of Native American culture and its treatment of actual Native Americans. A sense of unease pervades, mostly in small details like the College Photographer's subject heading ("Indians") for his files or the use of the title "Grand Sachem" in Ronwi's birth declaration. Sadly, we will never know how Bill Cook felt about the attention lavished upon his son by Dartmouth or about his time on campus: he died in a military flying accident in 1952 after being called back into service as a flight instructor.

Although the enthusiasm of the College seems genuine enough, its interactions with Ronwi and his parents reveal the struggle of the Dartmouth community to differentiate between its traditional appropriation of Native American culture and its treatment of actual Native Americans. A sense of unease pervades, mostly in small details like the College Photographer's subject heading ("Indians") for his files or the use of the title "Grand Sachem" in Ronwi's birth declaration. Sadly, we will never know how Bill Cook felt about the attention lavished upon his son by Dartmouth or about his time on campus: he died in a military flying accident in 1952 after being called back into service as a flight instructor.