These covers are just too good. We couldn't resist a follow up to the Christmas posting. Pears' Soap issued it's own holiday annual to compete with the London Illustrated News called Pears' Annual. The front cover was always a stunning holiday image and the back cover a suitably themed advertisement for Pears' Soap. In this case, the cover shows an infant 1894 ringing in the New Year and bidding the old 1893 farewell. A dead boar and fowl evoke the feasting of the season and the holly references Christmas.

The back cover shows the wonders of Pears' Soap with an image of an old man (could it be the same old man representing 1893 on the front?) invigorated and and pleased by his cleanly shaven chin. "Shaving a Luxury!" exclaims the headline.

Ask for Sine Serials AP4.349 and have a great 2015!

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

Tuesday, December 23, 2014

A Colorful Christmas

The Christmas tree, colorful packages, cards, the big family dinner... you know the schtick. You've seen it in the movies, heard it in so many Christmas carols, and perhaps even lived it. But how did that simple feast day from Medieval times turn into such a big deal? Was it, as Lucy Van Pelt claimed in A Charlie Brown Christmas, a result of a Big Eastern Syndicate?

The Christmas tree, colorful packages, cards, the big family dinner... you know the schtick. You've seen it in the movies, heard it in so many Christmas carols, and perhaps even lived it. But how did that simple feast day from Medieval times turn into such a big deal? Was it, as Lucy Van Pelt claimed in A Charlie Brown Christmas, a result of a Big Eastern Syndicate?The British Royal Family probably had more to do with it than any Syndicate. Prince Albert and Queen Victoria gathered their large family around a Christmas tree each year and celebrated with a feast. The public learned about it from the colorful annuals issued at the time. We have just finished cataloging an enormous collection of Victorian and Edwardian illustrated annuals. The color saturated chromolithograph covers did for Christmas what Norman Rockwell's Life covers did for the American Dream: richly and romantically illustrated it for middle class aspirations.

For some examples, ask for The Illustrated London News (Sine Serials AP4.I3) or Pears' Annual (Sine Serials AP4.P349)

Friday, December 19, 2014

Not So Saintly Patron

Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language (London: W. Strahan, 1755) is an authorial tour de force. That one person could possibly assemble a dictionary basically on his own of such a scope is astonishing. The two densely packed volumes took nine years of his life to write.

Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language (London: W. Strahan, 1755) is an authorial tour de force. That one person could possibly assemble a dictionary basically on his own of such a scope is astonishing. The two densely packed volumes took nine years of his life to write. Johnson received patronage of a sort for his work. Besides receiving money from a group of booksellers who supported the project, he also secured Lord Chesterfield's support through his Plan of a Dictionary (London: J. and P. Knapton, 1747). Chesterfield wrote an essay in support of the project, but in so doing, offended the sensitive Johnson. Johnson held a grudge and retaliated in a backhanded way in the dictionary itself. His first definition of "Patron" reads:

1. One who countenances, supports or protects. Commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.

Johnson buried a few other precious barbs in his text. He defines oats as "a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people."

Johnson buried a few other precious barbs in his text. He defines oats as "a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people."To see the Dictionary, ask for Rare PE1620.J6 1755. To see the Plan, ask for Val 825 J63 P69.

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

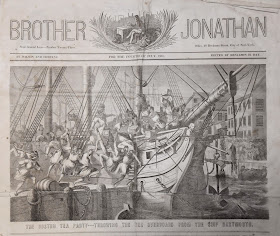

Aboard the Dartmouth

In late November 1773, the Nantucket whaling ship Dartmouth sailed into Boston harbor. Her cargo was tea, brought back from England after sailing there with a load of whale oil. At the time, much of the population of Boston had gotten a tad irritable about British taxation and duties on tea, so the Dartmouth was not allowed to unload her cargo. A few days later she was joined by the Eleanor, also loaded with tea and similarly detained in the harbor unable to unload. On December 15th, the Beaver arrived, and became the third ship that would, the next day, play a role in one of the pivotal events in this country’s fight for independence.

In late November 1773, the Nantucket whaling ship Dartmouth sailed into Boston harbor. Her cargo was tea, brought back from England after sailing there with a load of whale oil. At the time, much of the population of Boston had gotten a tad irritable about British taxation and duties on tea, so the Dartmouth was not allowed to unload her cargo. A few days later she was joined by the Eleanor, also loaded with tea and similarly detained in the harbor unable to unload. On December 15th, the Beaver arrived, and became the third ship that would, the next day, play a role in one of the pivotal events in this country’s fight for independence.We all know what happened to that tea in Boston harbor on December 16, 1773.

However, I had forgotten from my American history lessons of long ago that one of the Boston Tea Party ships was named Dartmouth. She was the first ship built in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1767 for Francis Rotch of Nantucket, and was named for a section of Bedford. Sadly, the Dartmouth was lost at sea on the Atlantic during the summer of 1774.

There have been other ships named Dartmouth, including a brig built by J. N. Harvey in 1768 and listed in Lloyd’s register of shipping for 1776. It was this vessel that caused some confusion over the rigging when Ruth Edwards was researching the Boston Tea party ship Dartmouth for a commission she had been given by the Class of 1907. The class gave the painting of the Dartmouth to the College in 1967 in honor of its upcoming bicentennial.

During World War II, an oil tanker, the Dartmouth, and a victory type cargo ship, the Dartmouth Victory, were launched. About the same time, two liberty cargo ships were launched: the Samson Occom and the Eleazar Wheelock. I suspect there are other ship with Dartmouth connections, but the vessels carrying the name of Levi Woodbury, Class of 1809, and Secretary of the Navy, are too numerous to go into here.

Ask for Iconography 1368 to see the "Tea Party" Dartmouth.

Friday, December 12, 2014

Trial and Conflict

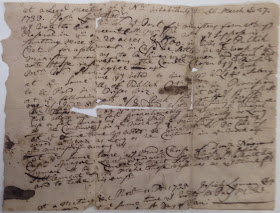

The adage that “all your dysfunctional relationships have one thing in common, you” comes to mind whenever Eleazar Wheelock’s legacy is up for examination. This is particularly the case with a recent acquisition of Wheelock documents (five in his hand) ranging from the time of his calling to the Second Congregational Church in Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1735 to 1771 after his arrival in Hanover.

The adage that “all your dysfunctional relationships have one thing in common, you” comes to mind whenever Eleazar Wheelock’s legacy is up for examination. This is particularly the case with a recent acquisition of Wheelock documents (five in his hand) ranging from the time of his calling to the Second Congregational Church in Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1735 to 1771 after his arrival in Hanover.Most of the documents deal with conflict: a court case, a disagreement between a minister and his congregation or between one minister and another. Others are less controversial and focus on the installment of a minister, or an invitation to Wheelock, a renowned preacher in his time, to give a sermon at another church.

One of the most interesting items in this group of documents is a scrap of well-worn paper in Wheelock’s hand that is coming apart at the creases. Picking through the chicken scratch it becomes evident these are notes that Wheelock took perhaps during the negotiations regarding his ministry in Lebanon, Connecticut. The notes outline what the congregation had agreed to provide Wheelock as compensation for his ministerial efforts, they specifically record that he would be paid £140 per year in public credit or provisions with the types of provisions and amounts carefully noted. The provisions included wheat, corn, oats and pork and beef. The notes also record that Wheelock was to be paid yearly on the first of January. This agreement was drawn up by a savvy group of flinty Connecticut farmers and businessmen who found ways to reinterpret it, or so Wheelock felt, to his disadvantage. It very soon became a source of conflict between Wheelock and the congregation that would plague him until resigned his position.

The crux of the issue appears to have been how these provisions were to be provided based on the rise and fall of their value. The deficit created by the congregation’s interpretation of this agreement was one of the factors that led Wheelock to take on students for tutoring as a way to supplement his income. This in turn led to his tutoring Samson Occom. It was Occom’s success as a scholar that led Wheelock to the idea of educating Native Americans. So, in a sense, this scrap of paper covered in scratchy hand, is the genesis for the eventual founding of Dartmouth College.

To see Wheelock's notes and two later “clean copies” that he made of the specific areas of disagreement, ask for MS-1310, box 1, folders 735227. 1, 735227.2, 735227.3

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

Welcome to Jenny Lind

Even the abolitionist singing group, the Hutchinson Family, tried to cash in on her fame with their "Welcome to Jenny Lind." Sung "on the occasion of her visit to America," it was quickly issued as sheet music (Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1850).

To see the Daguerreotype and ticket, ask for Iconography 292. To see "Welcome Jenny Lind," ask for Sheet Music HF 73.

To see the Daguerreotype and ticket, ask for Iconography 292. To see "Welcome Jenny Lind," ask for Sheet Music HF 73.

Friday, December 5, 2014

Winter Break

Things are pretty quiet here in Rauner Library since the students left for break. We just have a few folks in doing some research, but the hustle of the term is past and the classrooms are empty. Hanover is cold and grey in their absence, but peaceful, too.

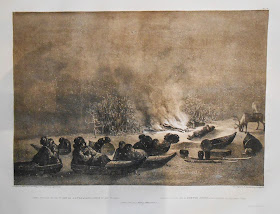

They all seemed pretty tired during finals week--wandering around in a daze, some in their pajamas. We like to imagine they are hunkered down now catching up on their sleep like in this lithographic image from Arthur de Capell Brooke's Winter Sketches in Lapland (London: J. Murray, 1827).

If the Hanover winter gets you too down, come in and take a look by asking for Stef DL971.L2 B7.

They all seemed pretty tired during finals week--wandering around in a daze, some in their pajamas. We like to imagine they are hunkered down now catching up on their sleep like in this lithographic image from Arthur de Capell Brooke's Winter Sketches in Lapland (London: J. Murray, 1827).

If the Hanover winter gets you too down, come in and take a look by asking for Stef DL971.L2 B7.

Tuesday, December 2, 2014

Oh, No!

We have quite a few examples of books and ephemeral material that served as propaganda during the First and Second World Wars. But this one caught us a little off guard. Published in 1939 in Warsaw, L'armée et la marine de guerre Polonaises, looks like a typical 1930s show of military muscle. For the most part, it is images of tanks, airplanes, heavy artillery and troops training. But, timing is everything, so the image of Poland's bicycle brigade stands out. It proudly shows rows of Polish infantry sitting astride bicycles tricked out with rifles in the handlebars.

We have quite a few examples of books and ephemeral material that served as propaganda during the First and Second World Wars. But this one caught us a little off guard. Published in 1939 in Warsaw, L'armée et la marine de guerre Polonaises, looks like a typical 1930s show of military muscle. For the most part, it is images of tanks, airplanes, heavy artillery and troops training. But, timing is everything, so the image of Poland's bicycle brigade stands out. It proudly shows rows of Polish infantry sitting astride bicycles tricked out with rifles in the handlebars.Published just months before Germany invaded from the West and the Soviet Union from the East, the bicycle brigade is now emblematic of just how ill-prepared Poland was to face either military force. It took just five weeks for the Germans and Soviets to seize and divide Poland.

To see the book, ask for Rare UA829.P7 K63 1939.

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Thanksgiving Tweets, 1946

| DOC Thanksgiving Feast, November 1946 Archival Photofiles |

"I'm glad I won't need to see The Dartmouth until next Monday."

"I am thankful that the New York Rangers beat the Canadians 3-2."

"I'm very thankful that I work for the Jack-o"

"I'm thankful that I go to a liberal arts college where I can learn how to be a liberal artist."

"I'm thankful for Hollywood failures."

"I'm thankful that after eating in Thayer Hall for two months I can go home for a decent meal."

"I'm thankful that I have two classes this afternoon so I can spend an extra day in Hanover."

To read more, take a look at The D on our reference shelves here in Rauner--but not on Thanksgiving. We'll be thankful to not be at work! The photofiles, though, will still be online.

Friday, November 21, 2014

Misappropriation

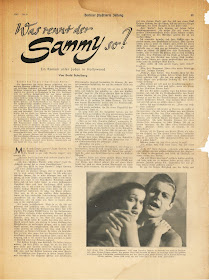

In 1941, Budd Schulberg '36 published his first novel: What Makes Sammy Run? As a child of the studios (his father had been head of Paramount), and a frustrated screenwriter, he unleashed a torrent of criticism on Hollywood in his novel about the rise of Sammy Glick. The novel became a bestseller in the United States and has often been pointed to as the great American novel about Hollywood.

In 1941, Budd Schulberg '36 published his first novel: What Makes Sammy Run? As a child of the studios (his father had been head of Paramount), and a frustrated screenwriter, he unleashed a torrent of criticism on Hollywood in his novel about the rise of Sammy Glick. The novel became a bestseller in the United States and has often been pointed to as the great American novel about Hollywood.Schulberg knew he was taking a risk when he published the novel. It was destined to offend many of the most powerful people in Hollywood. But he did not anticipate that the novel would become fodder for the Nazi propaganda machine. Sammy Glick, the novel's offensive, back-stabbing anti-hero, was Jewish. The Nazis picked up the story and produced a translation edited to highlight the offenses of Jews in Hollywood and portray Sammy as the quintessential American Jew. Then they published it serially in the popular Berliner Illustriere Zeitung where Schulberg's words were turned against the Jewish people.

Ironically, Budd and his brother Stuart were later employed by the U.S. military to splice together film footage to be used against Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg. Their work was made particularly effective by their juxtaposition of Nazi propaganda with scenes of atrocities. For Schulberg, the appropriation of Nazi propaganda must have been a particularly sweet form of personal revenge.

To see how Sammy looked in 1942 Berlin, ask for MS-978, Box 6, Folder 4. And, as a reminder, our current exhibition, Budd Schulberg and the Scripting of Social Change, runs through January 30, 2015 in the Class of 1965 Galleries. And, for more on Schulberg, see these postings from August 9, 2011 and November 4, 2014.

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

In the Best Interest of the College

25 years ago, on November 13th, 1989, the Board of Trustees announced the College’s intention to completely divest the endowment from companies operating in South Africa. This decision was the culmination of almost 20 years of protests and discussion between students, administrators, and community members regarding the propriety of the College’s involvement with companies that were complicit in apartheid.

25 years ago, on November 13th, 1989, the Board of Trustees announced the College’s intention to completely divest the endowment from companies operating in South Africa. This decision was the culmination of almost 20 years of protests and discussion between students, administrators, and community members regarding the propriety of the College’s involvement with companies that were complicit in apartheid.The 1970s and 1980s saw divestment movements arise at many colleges and other institutions in the midst of the public outcry over South Africa’s apartheid system. The College’s first action regarding the divestment question occurred in 1972, when the Trustees voted to form the Advisory Committee for Investor Responsibility, tasked with overseeing the ethical use of Dartmouth’s endowment. In 1977, Rev. Leon Sullivan issued a set of six principles of business ethics for companies operating in South Africa in order to maintain their American backers. Dartmouth and many of its peer institutions pressured the companies in which they had investments to sign on to the principles. However, by the mid-1980s the principles were considered too moderate and many organizations began to consider complete divestment.

The debate over apartheid and divestment at Dartmouth included several highly controversial protests and demonstrations. For example, in 1986, 13 students occupied Baker Tower and only came down after they were promised a meeting with the Board of Trustees to discuss the possibility of divestment. The most well-known protest by far, however, concerned several shanties built on the Green in late 1985 to protest the human rights violations of apartheid and the College’s refusal to divest. Students began living in the shanties and refused to leave despite the cold weather and the administration’s disapproval, but during the night of January 21st, 1986, a group of writers from The Dartmouth Review secretly gathered on the Green and destroyed the shanties with sledgehammers. The next day, nearly 200 outraged students occupied Parkhurst and the President’s Office to protest the attack, while more students rallied outside. President McLaughlin responded by suspending the students who had destroyed the shanties and canceling classes for one day to hold a teach-in exploring racism and prejudice at Dartmouth. While the protests quieted somewhat in the following years, groups such as the Dartmouth Community for Divestment, the Afro-American Society, and the Upper Valley Committee for a Free South Africa continued to pressure the Board of Trustees to divest until 1989, when they finally agreed to do so after a group of protesters stormed a meeting of the Trustees and called for an impromptu vote. The College continued to refrain from investments in South Africa until 1994, when it chose to end the policy following the overthrow of apartheid.

The debate over apartheid and divestment at Dartmouth included several highly controversial protests and demonstrations. For example, in 1986, 13 students occupied Baker Tower and only came down after they were promised a meeting with the Board of Trustees to discuss the possibility of divestment. The most well-known protest by far, however, concerned several shanties built on the Green in late 1985 to protest the human rights violations of apartheid and the College’s refusal to divest. Students began living in the shanties and refused to leave despite the cold weather and the administration’s disapproval, but during the night of January 21st, 1986, a group of writers from The Dartmouth Review secretly gathered on the Green and destroyed the shanties with sledgehammers. The next day, nearly 200 outraged students occupied Parkhurst and the President’s Office to protest the attack, while more students rallied outside. President McLaughlin responded by suspending the students who had destroyed the shanties and canceling classes for one day to hold a teach-in exploring racism and prejudice at Dartmouth. While the protests quieted somewhat in the following years, groups such as the Dartmouth Community for Divestment, the Afro-American Society, and the Upper Valley Committee for a Free South Africa continued to pressure the Board of Trustees to divest until 1989, when they finally agreed to do so after a group of protesters stormed a meeting of the Trustees and called for an impromptu vote. The College continued to refrain from investments in South Africa until 1994, when it chose to end the policy following the overthrow of apartheid.

To learn more about Dartmouth’s divestment movement, check out the display case in Rauner's reading room, just to the right of the doors. Sources for the exhibit are the Records of the Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility (DA-328), the Papers of George Bourozikas (DO-55), and archives files on student protests.

Posted for Hillary Purcell '15.

Friday, November 14, 2014

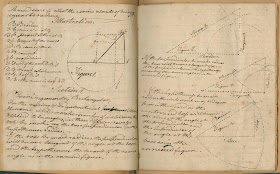

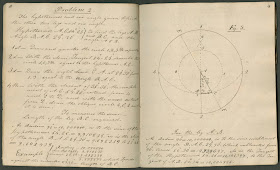

Ciphering Books

|

| Pike's Mathematical text |

Ciphering books were always written in ink, often with calligraphy headings and illustrations. However, the quality of the script varied significantly.

|

| Woodward's "System of Plain Trigonometry" |

|

| Hubbard's "System of Spheric Trigonometry" |

According to a M.A. Clements and Nerida F. Ellerton, mathematics professors at Illinois State University, the use of ciphering books declined after 1840, due to the fact that they were no longer important in evaluating the quality of a student's learning or that of an instructor's teaching. In addition, they argue that state education leaders switched their focus from the individual student to that of a graded class.

To see these ciphering books ask for: MS-1271 (Pike) and Codex 802415.1 (Woodward). Kimball's cipher book is currently being re-cataloged.

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Dartmouth Vietnam Project

Fifty years ago, Robert B. Field Jr., a newly minted Dartmouth ’64, was nearing the end of Officer Candidate School at Naval Station Newport in Rhode Island. He was two months away from a training assignment in Brunswick, Georgia, and shortly after that, he would ship out of Norfolk, Virginia aboard the USS Long Beach. The Long Beach would travel widely with Field aboard — to Roosevelt Roads Naval Station in Puerto Rico, back to Virginia, through the Panama Canal, up the West Coast to its namesake city in California, a stop at Pearl Harbor, another at Subic Bay in the Philippines — but by the close of 1965, it would be en route to the Gulf of Tonkin, Vietnam.

Fifty years ago, Robert B. Field Jr., a newly minted Dartmouth ’64, was nearing the end of Officer Candidate School at Naval Station Newport in Rhode Island. He was two months away from a training assignment in Brunswick, Georgia, and shortly after that, he would ship out of Norfolk, Virginia aboard the USS Long Beach. The Long Beach would travel widely with Field aboard — to Roosevelt Roads Naval Station in Puerto Rico, back to Virginia, through the Panama Canal, up the West Coast to its namesake city in California, a stop at Pearl Harbor, another at Subic Bay in the Philippines — but by the close of 1965, it would be en route to the Gulf of Tonkin, Vietnam.

As Field’s military service was unfolding, two Dartmouth ’68s were just beginning their studies. John C. Everett Jr. and John G. Spritzler both arrived on campus in the fall of 1964, and over the next four years, their paths would take markedly different turns. By 1969, Everett would be bound for Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, aboard the USS Gallup. Spritzler would be a committed anti-war activist and a central figure in a protest that defined an era in Dartmouth history: the seizure and occupation of Parkhurst Hall on May 6, and the ensuing standoff with police that lasted well into the night.

Decades after the last American troops withdrew from Vietnam, all three men sat down with a member of the Class of 2016 to share their memories of the war. Their conversations were audio recorded, and along with three others, now comprise the first products of the Dartmouth Vietnam Project. The DVP, a collaborative effort involving Dartmouth students, faculty, and staff, seeks to preserve and share the stories of alumni and other members of the wider Dartmouth community who experienced the Vietnam War years firsthand. Students specially trained in the art of oral history conduct the interviews, and the resulting audio and text transcripts become part of a growing oral history collection at Rauner.

As of Veterans Day 2014, the first six interviews — Field, Everett, and Spritzler among them — are available on a dedicated DVP website (http://www.dartmouth.edu/~dvp). In the coming months and years, more and more interviews from veterans, activists, and those with memories of the impact of the war on Dartmouth and American society in general will join the original six. If you or somebody you know has a story to share, visit http://www.dartmouth.edu/~dvp/participate.html.

Friday, November 7, 2014

Mao Zedong's Calligraphic Art

Although everyone knows that Mao Zedong was the founder of the People's Republic of China, few people in the Western world are aware that he was also a great poet and calligrapher. Throughout his life, Mao used brush and ink to draft the majority of his letters, party documents and to compose his famous poems. His calligraphy, characterized by its uniqueness, versatility and broadness of mind, has been established as "Mao style" (毛体) and is highly regarded by the Chinese people and especially by professional artists in China.

Although everyone knows that Mao Zedong was the founder of the People's Republic of China, few people in the Western world are aware that he was also a great poet and calligrapher. Throughout his life, Mao used brush and ink to draft the majority of his letters, party documents and to compose his famous poems. His calligraphy, characterized by its uniqueness, versatility and broadness of mind, has been established as "Mao style" (毛体) and is highly regarded by the Chinese people and especially by professional artists in China.Over many decades of his life, Mao studied a variety of classical calligraphy styles, and constantly explored, experimented and perfected his technique, establishing his distinctive cursive style.

Rauner Library recently purchased a rare edition of The Twenty-Four Histories with Mao Zedong’s annotation毛泽东评点二十四史. During the last twenty years of his life, Mao read the 850 volumes of Twenty-Four Histories several times and made extensive commentaries with his stylish calligraphy in the margins. On October 23rd, the Asian and Middle Eastern Languages and Literatures Department at Dartmouth hosted a public event on Mao’s calligraphy and manuscript art. The guest speaker, Professor Chen Chuanxi, a chair professor at Renmin University of China and a well-known art critic and art historian, shared his insights on the subject. In Professor Chan's opinion, Mao was the greatest cursive style calligrapher during the last three hundred years. Chan also said that Mao's commentaries on the Twenty-Four Histories reflected his in-depth understanding of Chinese history and exemplified his long term strategy of making the past serve the present.

Rauner Library recently purchased a rare edition of The Twenty-Four Histories with Mao Zedong’s annotation毛泽东评点二十四史. During the last twenty years of his life, Mao read the 850 volumes of Twenty-Four Histories several times and made extensive commentaries with his stylish calligraphy in the margins. On October 23rd, the Asian and Middle Eastern Languages and Literatures Department at Dartmouth hosted a public event on Mao’s calligraphy and manuscript art. The guest speaker, Professor Chen Chuanxi, a chair professor at Renmin University of China and a well-known art critic and art historian, shared his insights on the subject. In Professor Chan's opinion, Mao was the greatest cursive style calligrapher during the last three hundred years. Chan also said that Mao's commentaries on the Twenty-Four Histories reflected his in-depth understanding of Chinese history and exemplified his long term strategy of making the past serve the present.To see it ask for Mao's Twenty-Four Histories DS735.A2 E65 1996.

Posted for Nien Lin Xie

Tuesday, November 4, 2014

On the Waterfront: A Mission, Not a Movie Assignment

For Budd Schulberg, On the Waterfront was not a conventional movie assignment. It was a mission to make the voices of protesting longshoremen heard by bringing their struggles against organized crime on New York and New Jersey’s docks to the silver screen.

For Budd Schulberg, On the Waterfront was not a conventional movie assignment. It was a mission to make the voices of protesting longshoremen heard by bringing their struggles against organized crime on New York and New Jersey’s docks to the silver screen.

After reading a series of Pulitzer Prize winning articles by investigative journalist Malcolm Johnson, Schulberg found himself drawn to the longshoremen’s fight against corruption on the docks. Schulberg met with Johnson who cited Father John Corridan, a crusading labor priest from the St. Francis Xavier Labor School, as a prime source for his exposé of the brutal exploitation and cold-blooded murders of workers.

When Schulberg met Father Corridan, the priest was in the midst of guiding a group of rebel longshoremen in a protest movement to build a harbor-wide reform labor union and challenge the mob-infiltrated International Longshoremen’s Association. While Schulberg was conducting research about life on the waterfront, Father Corridan encouraged him to use his prestige as a nationally renowned novelist to bring the plight of the longshoremen to the attention of the wider American public. Despite Johnson’s original breakthrough series, the city’s main media outlets, from the New York Times to the lurid tabloids, completely ignored the rampant crimes on the docks.

When Schulberg met Father Corridan, the priest was in the midst of guiding a group of rebel longshoremen in a protest movement to build a harbor-wide reform labor union and challenge the mob-infiltrated International Longshoremen’s Association. While Schulberg was conducting research about life on the waterfront, Father Corridan encouraged him to use his prestige as a nationally renowned novelist to bring the plight of the longshoremen to the attention of the wider American public. Despite Johnson’s original breakthrough series, the city’s main media outlets, from the New York Times to the lurid tabloids, completely ignored the rampant crimes on the docks.

It thus became Schulberg’s mission to make the voices of the protesting longshoremen heard by bringing their struggles to the silver screen. Working closely with producer Elia Kazan, Schulberg finished writing the screenplay for On the Waterfront in 1954. The film scored at the box office, won eight Academy Awards, and has been hailed as one of the top ten films of all time. More important for Schulberg than all the accolades and awards, however, was that the film achieved Father Corridan’s simple hope: to make the American people aware of the dire need for advancing labor reforms on the waterfront.

Schulberg’s interest in labor issues did not begin while writing the screenplay for On the Waterfront. As editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth in 1935, Schulberg reported on a series of marble quarry workers’ strikes. Schulberg’s accounts of these strikes foreshadow the investigative reporting he would carry out about waterfront crime over a decade later in New York.

Schulberg’s interest in labor issues did not begin while writing the screenplay for On the Waterfront. As editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth in 1935, Schulberg reported on a series of marble quarry workers’ strikes. Schulberg’s accounts of these strikes foreshadow the investigative reporting he would carry out about waterfront crime over a decade later in New York.

To learn more about On the Waterfront and Schulberg’s involvement in labor reform, come and see the exhibit currently on display at Rauner. The exhibit, “Budd Schulberg and the Scripting of Social Change,” will be on display from November 6th through January 30th. A symposium celebrating Schulberg’s centennial will also be held at Dartmouth November 6th and 7th which is free and open to the public.

Friday, October 31, 2014

More Cowbells

|

| Book of Hours Codex MS 001598 |

|

| Thomas Rowlandson, Illus R796ce |

Try these images from our collections on for size. You'll need to drop the cloak... and your skin as well.

Book of Christian Prayers, Rare BV245.D35 1581

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

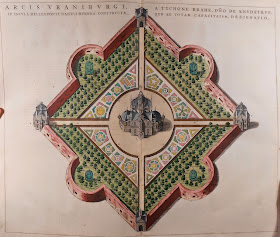

Brahe and Blaeu

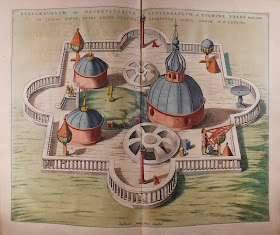

We have talked before about our luxurious hand-colored copy of the eleven-volume Blaeu Atlas, Geographia (Amsterdam, 1662), but never delved into a curious digression in the first volume. As you move along through maps of northern Europe in a fairly predictable pattern, you suddenly find yourself zeroing in on unexpected details on the island of Hvæna. There, the atlas takes the reader on a tour of Tycho Brahe's observatory with fourteen full-page or double-page engraved illustrations.

We have talked before about our luxurious hand-colored copy of the eleven-volume Blaeu Atlas, Geographia (Amsterdam, 1662), but never delved into a curious digression in the first volume. As you move along through maps of northern Europe in a fairly predictable pattern, you suddenly find yourself zeroing in on unexpected details on the island of Hvæna. There, the atlas takes the reader on a tour of Tycho Brahe's observatory with fourteen full-page or double-page engraved illustrations.Why this obsession? It is likely that Joan Blaeu was giving a nod to his father Willem Blaeu who started the family mapmaking business. Willem had been a student under Brahe at Hvæna, and it was during his time with Brahe that he developed his skills constructing globes. It is also a gesture to Joan Blaeu's own qualifications. The attention given to Brahe's measurement instruments suggests a certain level of technical expertise, thus elevating the already grand atlas through association.

To enjoy a walk through Brahe's observatory at Hvæna, ask for volume 1 of Rare G1015.B48 1662.

Friday, October 24, 2014

The Wives of Bath

The Wife of Bath is arguably the most enduringly provocative character created by Chaucer. A serial monogamist who has outlived four of her husbands (and is working on her fifth), she describes herself in the prologue to the Canterbury Tales as being well-versed in the arts of love, especially those practiced in the bedroom. Later, when the Wife of Bath tells her tale about courtly love, she references a fable in which a lion and man examine a painting of a man killing a lion. The lion asks, "Who painted the lion?" suggesting that if a lion had done the job, the outcome would have been much different.

The Wife of Bath is arguably the most enduringly provocative character created by Chaucer. A serial monogamist who has outlived four of her husbands (and is working on her fifth), she describes herself in the prologue to the Canterbury Tales as being well-versed in the arts of love, especially those practiced in the bedroom. Later, when the Wife of Bath tells her tale about courtly love, she references a fable in which a lion and man examine a painting of a man killing a lion. The lion asks, "Who painted the lion?" suggesting that if a lion had done the job, the outcome would have been much different. With that in mind, we decided to take a look and see how the Wife of Bath herself has been depicted by various men at various times (as well as obviously being the creation of a man from the start). Displayed here are three artists' renderings. The first is a woodcut from the 1542 edition of Chaucer's Workes; the second, an engraving by William Blake in 1810; and the third by Blake's rival engraver Thomas Stothard from 1817. Each of them provides a different interpretation of the Wife of Bath, be it a typical (if somewhat austere-looking) woman of means from the medieval period, a bawdy and drunken profligate, or a flirtatious high-brow lady. All of these images display an aspect of the Wife of Bath, but we would argue that none of them truly encapsulates her essence.

With that in mind, we decided to take a look and see how the Wife of Bath herself has been depicted by various men at various times (as well as obviously being the creation of a man from the start). Displayed here are three artists' renderings. The first is a woodcut from the 1542 edition of Chaucer's Workes; the second, an engraving by William Blake in 1810; and the third by Blake's rival engraver Thomas Stothard from 1817. Each of them provides a different interpretation of the Wife of Bath, be it a typical (if somewhat austere-looking) woman of means from the medieval period, a bawdy and drunken profligate, or a flirtatious high-brow lady. All of these images display an aspect of the Wife of Bath, but we would argue that none of them truly encapsulates her essence. To form your own opinion in person, come in and examine these images of Alysoun yourself. To see the Blake, ask for Iconography 1596; the Stothard, Iconography 1661; and the 1542 edition, Hickmott 101.

To form your own opinion in person, come in and examine these images of Alysoun yourself. To see the Blake, ask for Iconography 1596; the Stothard, Iconography 1661; and the 1542 edition, Hickmott 101.Tuesday, October 21, 2014

Gabberjabb

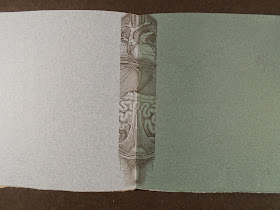

So what exactly is a Gabberjabb? When you flip through Walter Hamady’s Gabberjabb No. 6, you encounter a multi-layered, surrealist autobiography that walks a tightrope between sense and nonsense. Hamady’s art epitomizes the virtues of letterpress printing and book design while simultaneously poking fun at assumptions about the structure and function of books. In Gabberjabb No. 6 (its lengthier official title is Neopostmodrinism or Dieser Rasen ist kein Hundeklo or Gabberjabb Number 6), Hamady seeks to expand the book form by disturbing codified reading conventions and exploring the nuances of typography through continuously footnoted poetry and prose.

So what exactly is a Gabberjabb? When you flip through Walter Hamady’s Gabberjabb No. 6, you encounter a multi-layered, surrealist autobiography that walks a tightrope between sense and nonsense. Hamady’s art epitomizes the virtues of letterpress printing and book design while simultaneously poking fun at assumptions about the structure and function of books. In Gabberjabb No. 6 (its lengthier official title is Neopostmodrinism or Dieser Rasen ist kein Hundeklo or Gabberjabb Number 6), Hamady seeks to expand the book form by disturbing codified reading conventions and exploring the nuances of typography through continuously footnoted poetry and prose.

In Gabberjabb No. 6, Hamady calls attention to the structural elements of book form that are normally taken for granted by readers, such as title pages, indices, footnotes, signatures, margins and gutters, and makes them the centerpiece of the book.

In Gabberjabb No. 6, Hamady calls attention to the structural elements of book form that are normally taken for granted by readers, such as title pages, indices, footnotes, signatures, margins and gutters, and makes them the centerpiece of the book.

A particularly memorable play on book form in Gabberjabb No. 6 consists of a series of page gutters adorned with anatomical drawings of intestines. Hamady draws attention to an empty section of the page that most people never see because of centuries of reading conventions that have conditioned us to focus on the text block in the center of the page and disregard the empty space surrounding it. For Hamady, the gutter or “guts” of an open book is the center of the picture plane and should be considered a significant structural element of the book.

Through his ingenious and abstract play on book structure, Hamady warns against the kind of reductive reading that focuses on the book’s content at the expense of its form. The self-conscious manipulation of standardized rules regulating book form is intended to increase the readers’ awareness that such conventions exist and influence the construction of meaning. In many ways, this book can be considered a meta-critique on conventional understandings of “bookness”; it seeks to challenge our traditional notions of book form by reevaluating how form works in conjunction with content to convey meaning.

To see Gabberjabb No. 6, ask for Presses P4187hne. Gabberjabb No. 6 is part of an eight volume series called Interminable Gabberjabbs and volumes 5-8 are available at Rauner as well, along with over twenty other artists’ books by Hamady.

Friday, October 17, 2014

Homecoming: Edmund B. Dearborn

We recently acquired a small collection of letters addressed to Edmund B. Dearborn. Dearborn was a New England schoolteacher, who, although he prepared for college at Hampton Academy in New Hampshire, never matriculated at an institution. At Hampton Academy, Dearborn was a member of the Olive Branch Society. Incorporated in 1832, the society was founded to promote and improve writing and public speaking skills. However, when a fire at the Academy destroyed their collection of about six hundred valuable books, the society ceased to exist.

We recently acquired a small collection of letters addressed to Edmund B. Dearborn. Dearborn was a New England schoolteacher, who, although he prepared for college at Hampton Academy in New Hampshire, never matriculated at an institution. At Hampton Academy, Dearborn was a member of the Olive Branch Society. Incorporated in 1832, the society was founded to promote and improve writing and public speaking skills. However, when a fire at the Academy destroyed their collection of about six hundred valuable books, the society ceased to exist.

The letters in the collection are primarily from Dearborn's former schoolmates. Most had also been members of the Olive Branch Society and many of them went into teaching as well. The letters detail the routine, responsibilities and personal narratives of small town schoolteachers.

Several of them attended Dartmouth College and it is through these letters that we get a first-hand account of student life at Dartmouth in the first half of the 19th century. In a letter from September 1829, Joseph Dow '33 describes his life at Dartmouth, commenting that the "situation [here] is indeed very fine," and that the "situation of Dart. Coll. has been grossly misrepresented." He also implies that he expected Dearborn to join him at Dartmouth the following year and that in preparation for that he would "endeavor to give [him] some ideas of the place by the following uncouth figure." Dow follows this statement with a small drawing in which he describes the buildings in "their situation relative to each other." He also describes the Tontine building, which was destroyed in a fire in 1887, as a

huge building of brick, four stories high and part of a day's journey in length. The lower part contains the Jackson Post Office-lawyer offices- tin plate worker's shop-saddlers etc. The upper part contains rooms for students - principally quacks

Another former member of the Olive Branch Society, John Calvin Webster '32 describes a more

Another former member of the Olive Branch Society, John Calvin Webster '32 describes a more notorious incident when he writes that even though he had no particular news:

last week a negro woman died and was buried and on the night ensuing some of the medical students attempted to dig up the body. There were watchers expecting the attempt would be made, who let them dig down within a few inches of the coffin when they seized them.Other correspondents in this collection include Amos Tuck, Jesse Eaton Pillsbury, S. P. Dole and David P. Page. To look at these letters please ask for MS-1290.

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

Fantasy Football

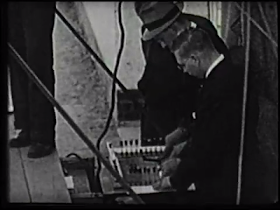

Last fall, a new high-definition video scoreboard was erected on Memorial Field. Unbeknownst to most Big Green fans today, this marked the 90th anniversary of a different type of scoreboard: the Grid-Graph from November 1923. In fact, this scoreboard never saw the field at all—it was set up in a handball court at the gym, to recreate away games at home for those who couldn’t make the trip.

Last fall, a new high-definition video scoreboard was erected on Memorial Field. Unbeknownst to most Big Green fans today, this marked the 90th anniversary of a different type of scoreboard: the Grid-Graph from November 1923. In fact, this scoreboard never saw the field at all—it was set up in a handball court at the gym, to recreate away games at home for those who couldn’t make the trip.The Grid-Graph board measured 15 feet by 12 feet and featured a glass replica of a football field. The team names, score, and number of downs were listed across the top, and player names along the sides. Below that were the various plays, like punt, interception, or touchdown. Operating the board was a multi-person production. One man made transcripts of the Morse code coverage coming in by telegraph, and then another relayed these as instructions to those controlling the lights. A switchboard operator lit up a bulb next to the play being made and the players involved. Meanwhile, a final man moved a free-standing bulb behind the glass to represent the ball’s position on the field. Of course, he only knew the yard markings and not the ball’s exact spot, so some artistic flourishes were allowed to create drama and suspense.

The board cost a thousand dollars at the time, but seems to have been well worth it. Wooden stands in front of the Grid-Graph filled up half an hour early, and each audience member paid admission. During the game, someone led cheers (though there was no team to hear them) and vendors walked among the crowd selling hot dogs and soda. The audience could even get rowdy. In the October 1980 Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, one Grid-Graph operator recalled a game in 1931, when Dartmouth made a miraculous 23-point comeback to tie with Yale. The fans went wild. As in, ravenous.

The board cost a thousand dollars at the time, but seems to have been well worth it. Wooden stands in front of the Grid-Graph filled up half an hour early, and each audience member paid admission. During the game, someone led cheers (though there was no team to hear them) and vendors walked among the crowd selling hot dogs and soda. The audience could even get rowdy. In the October 1980 Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, one Grid-Graph operator recalled a game in 1931, when Dartmouth made a miraculous 23-point comeback to tie with Yale. The fans went wild. As in, ravenous.“That crowd came out of those swaying stands and across the floor bent on getting some souvenirs of the game from the board. We had to rush out in front and fend them off or the whole thing would have caved in on us all. They tore out the players’ names and got a few lights, but we saved the board.”

Although the board survived that trial, it would not survive dwindling attendance and funds over the following decade. In 1941, the Grid-Graph was quietly put to rest.

To see pictures of the old Grid-Graph and a cardboard replica, ask for Rauner Photo Files: Football—Grid-Graph Board. Or, see them online here from the Digital Library Program.

Friday, October 10, 2014

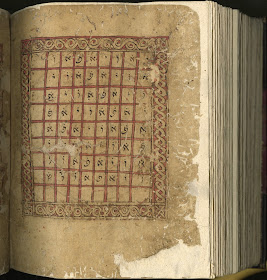

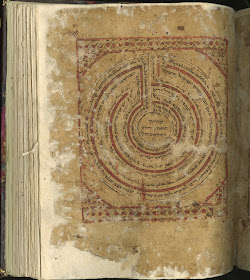

Taj Torah

We just acquired a truly amazing manuscript that has us all a twitter (though we don't Tweet, just blog!). The manuscript is a copy of the Taj Torah produced in Yemen c. 1400-1450. This is one of only three known Hebrew manuscripts with illustrated carpet pages. The Torah is prefaced with a copy of the Tajim, a Yemenite grammar and guide to reading the Torah, so the manuscript is both a sacred text and a pedagogical device for its reading.

We just acquired a truly amazing manuscript that has us all a twitter (though we don't Tweet, just blog!). The manuscript is a copy of the Taj Torah produced in Yemen c. 1400-1450. This is one of only three known Hebrew manuscripts with illustrated carpet pages. The Torah is prefaced with a copy of the Tajim, a Yemenite grammar and guide to reading the Torah, so the manuscript is both a sacred text and a pedagogical device for its reading.The manuscript has many possible uses in the classroom at a time when medieval and early modern Jewish texts are growing in interest and importance in academia. The specific aspects of it that most excite us are the carpet pages that can be compared and contrasted with Western illuminations and elucidate children's education in the middle ages, and the potential for discussion of the manuscript as an object (i.e., its construction, material components). Among the nice carpet pages are a drawing of the labyrinth of Jericho and a "Magical Square" of letters in a pattern.

Two years ago we worked with a class on medieval Christian, Islamic and Jewish traditions. We were able to lay out excellent medieval representations of the Koran and the Vulgate Bible but we lacked a comparative example of the Torah or similar Jewish text. That gap is now filled. We are able to lay, side by side, representative texts from all three monotheistic faiths, and all from roughly the same time period.

To take a look, come to Special Collections and ask to see Codex 003265.