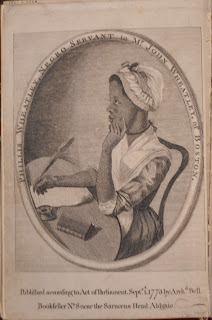

Phillis Wheatley was the first African American poet: born in West Africa in 1753, brought to America on the slave ship, The Phillis, she was sold into slavery at age eight to the Wheatley family in Boston. The Wheatley children provided her with a solid classical education and she began writing poetry. Her Poems on Various Subjects was published in London in 1773, and she became a celebrity in Europe and America.

Phillis Wheatley was the first African American poet: born in West Africa in 1753, brought to America on the slave ship, The Phillis, she was sold into slavery at age eight to the Wheatley family in Boston. The Wheatley children provided her with a solid classical education and she began writing poetry. Her Poems on Various Subjects was published in London in 1773, and she became a celebrity in Europe and America.We have several important pieces by Wheatley, two manuscript poems in her hand, a presentation copy of her first book, and her 1770 Elegy on the Death of George Whitefield, but the object that often stands out is something she did not write.

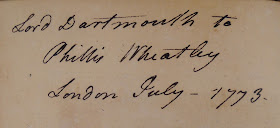

It is a memento of her 1773 trip to London where she was presented to London society and even invited to visit King George III. During the trip she met Lord Dartmouth, yes, our Lord Dartmouth, who offered her a gift of an edition of Pope's translation of the Iliad. The gift must have had a certain resonance for Wheatley: according to most accounts she had studied Pope and read Virgil in Latin. Holding the book forces you into a very foreign world, one where a young woman could be feted in London and held up as a celebrated poet, yet remain a slave to a Boston family.

It is a memento of her 1773 trip to London where she was presented to London society and even invited to visit King George III. During the trip she met Lord Dartmouth, yes, our Lord Dartmouth, who offered her a gift of an edition of Pope's translation of the Iliad. The gift must have had a certain resonance for Wheatley: according to most accounts she had studied Pope and read Virgil in Latin. Holding the book forces you into a very foreign world, one where a young woman could be feted in London and held up as a celebrated poet, yet remain a slave to a Boston family. Did the book travel with her through the rest of her life? Probably not. It is likely she had to sell it for money. Freed in 1778, she married a free black grocer. They ran into financial difficulties and he was put into debtors prison. Placed into a different sort of bondage by poverty, Wheatley became a domestic servant to support herself and died at age 31.

You can see all of these pieces: ask for DC History PA4025.A2P6 1771 for The Iliad; Ticknor PS866.W5 1773 for the Poems; Ticknor 772501.1 for the manuscript poem above; and Rare PS866.W5 E5 1770 for the Elegiac Poem.