We've recently rediscovered a copy of an early printed work by of one

of the most famously unprintable poets of the 17th century. John

Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester (1647-1680), was notorious in the

English court for his witty, sometimes bawdy poetry, which frequently

satirized the lives of well-known court figures - even King Charles

II.

We've recently rediscovered a copy of an early printed work by of one

of the most famously unprintable poets of the 17th century. John

Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester (1647-1680), was notorious in the

English court for his witty, sometimes bawdy poetry, which frequently

satirized the lives of well-known court figures - even King Charles

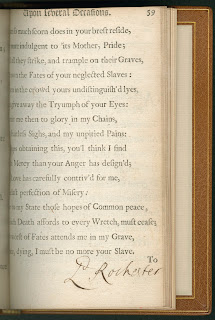

II.Before his death in 1680, only a handful of Rochester's poems appeared in print. The two poems by Rochester that appear in our copy of A Collection of Poems, Written upon Several Occasions, by Several Persons (London: Hobart Kemp, 1672) are the third appearance of Rochester's poetry in print and the first publication of his love elegies. In Kemp's compilation, both of Rochester's poems are titled "To Celia," but in modern editions they are known as "The Advice," and "The Discovery."

Also appearing in this miscellany is George Etheridge's "The Imperfect Enjoyment," which is titled identically to one of Rochester's most famous lyrics. Rochester's poem on the theme of premature ejaculation, unlike Etheridge's, was considered unprintable for centuries.

Rochester's poetry made its rounds through the English court almost exclusively in manuscript form, which means that our recent find is both quite rare and an excellent example of how scribal and print publication coexisted long after the invention of the printing press. Longhand copies, made either by Rochester himself, his friends, or professional scribes, meant that poems could circulate quickly and discreetly. At least one of these manuscript copies found its way to Kemp, who likely included it in this collection of poems without notifying Rochester (or paying him for his work).

Kemp never names the "several persons" whose works make up his miscellany; we realized the poems were Rochester's only because a previous owner inked in the authors' names at the end each work. A quick check with a modern critical edition confirmed the attribution. Ironically, because the surviving manuscript sources are sometimes conflicting and often ambiguous, the authorship of some poems attributed to Rochester is still contested.