As Derby Day approaches, we thought it might be fun to travel back in time and across the pond to look at 19th-century engravings of the original race responsible for the creation of the Kentucky Derby and other similar races. The Epsom Derby was (and is) held annually at the Epsom Downs just outside of London, where it began in 1780. These particular images of the Epsom Derby were created by Gustave Doré, a prominent 19th-century French artist and engraver. He first came to prominence in England because of his captivating illustrations in a new English Bible, printed in 1866. The success of this work opened professional doors for Doré in London, and several years later he collaborated with Blanchard Jerrold on a work entitled London: A Pilgrimage (London: Grant & Co., 1873).

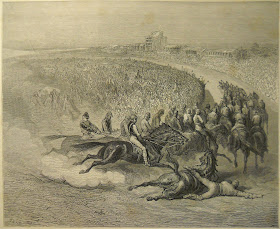

As Derby Day approaches, we thought it might be fun to travel back in time and across the pond to look at 19th-century engravings of the original race responsible for the creation of the Kentucky Derby and other similar races. The Epsom Derby was (and is) held annually at the Epsom Downs just outside of London, where it began in 1780. These particular images of the Epsom Derby were created by Gustave Doré, a prominent 19th-century French artist and engraver. He first came to prominence in England because of his captivating illustrations in a new English Bible, printed in 1866. The success of this work opened professional doors for Doré in London, and several years later he collaborated with Blanchard Jerrold on a work entitled London: A Pilgrimage (London: Grant & Co., 1873).This large folio contains breathtaking engravings by Doré, who is the true star of the work despite Jerrold’s narration. In Chapter Seven, titled, "the Derby," Doré manages to demonstrate the mass of London humanity that turned out annually in May under the pretense of seeing the races, an event that often was more about letting off carnivalesque steam than focusing intently on the horses. However, as Doré shows us in the image of the fallen horse and rider, there was also an element of excitement, danger, and darkness within the races themselves that held a universal appeal.

In this book, Doré’s representations of darkness do not confine themselves to day-lit public games and races. London: A Pilgrimage was criticized by contemporaries for displaying numerous scenes of London’s dirty back-streets and darkened alleyways where the poor and destitute huddled in squalor, as exemplified by this night scene from the Whitechapel neighborhood. Hearkening back to Dickens, Doré and Jerrold unflinchingly display all of London’s social classes. Above all, one leaves London: A Pilgrimage with the unshakeable feeling of claustrophobia, of exciting noisy streets and of the jostling chaos of the crowds that swelled around pilgrims to England’s capital.

To wander the teeming streets of 19th-century London for yourself, race over to Rauner and ask for Illus D73j.