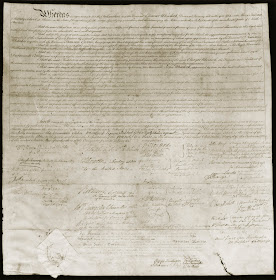

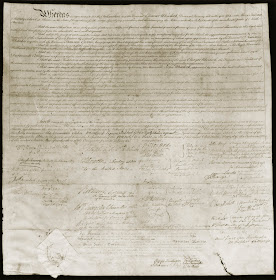

This document, which is much more impressive when you see it in real life since it is quite large at 26.5 x 27 inches, is John Wheelock's passport. Though actually a letter of introduction, it served a similar purpose to today's modern document and contains the signatures of George Washington and congressional members representing twelve of the thirteen colonies, all of whom supported John's mission to Europe to raise additional funds for the fledgling college.

|

| Washington's Signature |

The "passport" actually starts with the story of Eleazar Wheelock's first trip to the old world. The elder Wheelock had initially supplemented his income as a minister by tutoring and had taught an Indian student named Samson Occom who eventually went on to become a minister in his own right. Buoyed by this success Wheelock devised the idea that he could Christianize the "heathen" by training select native boys for the ministry.

In 1765 he sent Occom, in the company of another minister, Nathaniel Whitaker to England to raise funds so that he could start a school. People flocked to see Occom preach and his performances must have been impressive because the trip was a resounding success as Occom and Whittaker collected about £12,000 - the approximate equivalent of $1.3 million dollars in today’s money. They reported £9494 raised in England and another £2529 raised in Scotland - though the Scottish money was never actually received. The money allowed Wheelock to begin the process of creating the institution that would in 1769 become Dartmouth College, which he named after one of the most generous English donors, Lord Dartmouth.

|

| John Wheelock |

Unfortunately, John Wheelock’s venture was not as well favored. He and his brother James set out for France and on arrival in Paris met with Benjamin Franklin who was polite, but less than happy to see them. Franklin was just arranging for a large grant in aid from the French government and did not want to damage his prospects. He packed the Wheelock brothers off to the Netherlands as quickly as he could, where they managed to raise some funds, but the burgeoning peace agreement between England and the U.S. and its potential damage to Dutch trade prevented the level of giving they had hoped for. They next traveled to England where their reception was cool, but polite. While a few people were willing to give to their cause the takings were minimal.

On the return voyage their ship sank in a storm off the coast of Cape Cod and all the money, instruments and documents they were carrying were lost causing John’s detractors to claim that the trip barely paid for itself. The irony is that despite this early set back, John Wheelock, who is a bit of a villain in the history of the College, brought Dartmouth to financial solvency for the first time in its history before he died.

Ask for Mss 781681 to see the "passport."

Enormously popular and critically maligned, the dime novel was one of the first forms of mass culture in the United States. The Western adventure story dominated the dime novel industry in the 1860s and 1870s. Tales of the frontier, wherever it was – upstate New York, the Great Plains, or the California gold country – defined a mythical American identity. These “Books for the Million!” justified Western expansion with mail-order myths of violent transgressions, passionate romances, and thrilling rescues.

Enormously popular and critically maligned, the dime novel was one of the first forms of mass culture in the United States. The Western adventure story dominated the dime novel industry in the 1860s and 1870s. Tales of the frontier, wherever it was – upstate New York, the Great Plains, or the California gold country – defined a mythical American identity. These “Books for the Million!” justified Western expansion with mail-order myths of violent transgressions, passionate romances, and thrilling rescues.