Which did you like better, the book or the movie? Whatever your preference, you probably assume that film adaptations of books have some authorized relationship to the original version of the story. But this wasn’t always the case.

Which did you like better, the book or the movie? Whatever your preference, you probably assume that film adaptations of books have some authorized relationship to the original version of the story. But this wasn’t always the case.Nowadays it is astonishing to think that writers would not have the rights to control how their creative work is adapted. Many bestselling authors routinely negotiate the film rights to their novels before they are published. Copyright law is firmly in favor of authors retaining the rights to their creations, and Congress has repeatedly extended copyright protection (in the United States, it is currently the life of the author plus seventy years for most works) every time it has come up for renewal in recent decades.

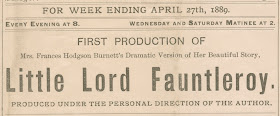

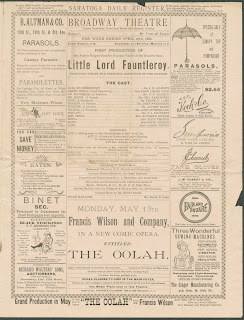

The contemporary protection of international copyright in this sense is only about a century old. Frances Hodgson Burnett, author of The Secret Garden (1911), was instrumental in advocating for authors’ rights to retain control of how their novels and characters are adapted. Her bestselling novel Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886), while protected at the time in the United States, was adapted into a play in London without her permission. Burnett was angered by this unauthorized use, and successfully sued to retain control of her creation. The lawsuit set a precedent that led to stronger laws protecting creative works from piracy and unlicensed adaptation. So nowadays, when you see a movie or a play that’s been adapted from a novel, trust that the original author had some say in how the work was presented – thanks in part to Frances Hodgson Burnett.

“Cultivating Secret Gardens: Frances Hodgson Burnett and Children’s Fiction” was curated by Laura Braunstein and Jay Satterfield and will be on display in the class of 1965 Galleries until August 31, 2011.

The exhibition is mounted in conjunction with “100 Years of The Secret Garden: A Centenary Conference,” July 29-30, 2011, at Dartmouth College. For more information, go to The Leslie Center for the Humanities event site.